(Part One)

This post is the second in my brief series on the ethics of pornography. The series works off the pair of essays on this topic in the book Contemporary Debates in Applied Ethics . We are currently going through Andrew Altman’s “pro”-pornography essay. As we saw the last day, Altman argues that the more general right to sexual autonomy entails (perhaps only weakly) the right to produce and access pornography. Although, he makes the case by way of analogy with the right to access and produce contraceptives, or the right to engage in premarital sex.

We closed the last post by briefly considering the counterargument to Altman’s view. This counterargument can be briefly stated as follows (numbering builds upon what was established in the previous post):

- (4) People have a right to do X if and only if X does not cause harm to others.

- (5) Pornography causes harm to others.

- (3*) Therefore, people do not have a right to produce and access pornography.

The key to this, of course, is premise (5). What reason do we have to think that pornography causes harm to others? That’s what we’re going to focus on today.

1. Does Pornography cause Sexual Violence against Women?

A common rejoinder to the proponent of a right to pornography is the following. Pornography can often depict situations involving sexual violence against women. And even if no one is actually harmed during the filming or photographing of such scenes (a topic to which we shall return), it could still be the case that viewing such material increases the likelihood of certain viewers carrying out similar acts of violence against women. To put it more pithily: there could be an indirect causal link between pornography and sexual violence. And since sexual violence is indubitably a kind of harm, it would follow that pornography would cause harm to others.

Now you’ll note the liberal use of “woulds” and “coulds” in the previous paragraph. So far, this argument is strictly hypothetical because we don’t know whether the indirect causal link actually exists. At this point, some empirical evidence is required. Unfortunately, when this happens — and when the topic is beyond my area of expertise — I begin to despair. The fact is, I have no real idea of where the evidence points on this one. All I can do is tell you what Altman says.

So what does he say? He says that the available evidence does not support the existence of any robust causal link between viewing pornography and sexual violence. In reaching this conclusion, he is particularly influenced by the work of Joseph Slade in his 2001 book Pornography and Sexual Representation . Slade says that some existing studies show weak links, while others show no links, and still others suggest an inverse relationship between pornography and sexual violence. This seems like an area where good meta-analyses are needed. Does anyone reading this know of any?

Altman makes a couple of other supporting observations. One is that if this is the kind of argument you’re going to make, then there is no reason to single out pornography for special treatment: other types of violent media probably have similar effects, why not ban them too? Of course, this kind of rhetorical ploy could easily backfire: someone could go ahead and bite the bullet and argue that we need to ban all violent media. But let’s assume the ploy works as Altman wants it to, does it follow that we should not restrict pornography? Not necessarily; it could be that sexual violence is particularly problematic and particularly worthy of precautionary treatment. I’d be willing to pursue that line of argument, but fortunately Altman touches upon it by discussing the potential concerns about pornography and the subordination of women. We’ll talk about that next. Before we do though, let’s summarise the argument so far as a pair of premises:

- (5.1) Men who view violent pornography are more likely to engage in sexual violence.

- (6) Evidence of a connection between pornography and violence is not robust.

We’ll be plugging these into the argument map at the end.

2. Does Pornography Contribute to Sexual Inequality

Here’s a second line of reasoning in support of premise (5): Pornography often displays women in humiliating and degrading positions. As a result, it influences the attitudes of those who use pornography towards women. It encourages them to see women as sexual objects, sources of gratification, things to played with then disregarded; it does not encourage them to treat women as moral equals. This is probably bad in itself, but it is certainly exacerbated when it takes place within a society that is already struggling to shake off the shackles of sexism. So:

- (5.2) Pornography degrades and subordinates women, and thereby contributes to a society that degrades and subordinates women.

Altman is even less impressed by this claim than he is by the claimed link between violence and pornography. First off, he thinks there is little reason to conclude that the sexual acts depicted in pornography are inherently degrading. And second, he says there is very little evidence to suggest that open access to pornography is correlated with subordination and sexism in society at large, let alone causally-linked to it. It seems like Altman is on reasonably strong grounds here: correlational evidence suggests that the most sexually inhibited societies, the one’s with the least liberal policies on pornography (Saudi Arabia is mentioned) are the ones where women suffer the most.

- (7) Evidence suggests that societies with open access to pornography are better places for women to live.

While this looks like a strong point, I wonder if we are yet to see the full social impact of the widespread availability of pornography in modern liberal societies. The internet has only really begun to dominate how we access information in the past ten years. And it has resulted in the near-universal access to pornography. This allows people of all ages to access pornography on an unprecedented scale. So I’d be on the lookout for more data on this in the future.

3. Does the Porn-Industry Harm Women?

A third, and for now final, way in which to support premise (5) is to say something like the following: Some (many?) women who participate in the production of pornographic material are harmed in the process of making it. This harm can range from straightforward criminal coercion, to more subtle forms of psychological harm. Thus, even if it is true that some (or many) women who do participate in the production of pornographic material are not harmed, there is still reason to restrict it.

- (5.3) Women who participate in the pornographic industry are harmed.

Altman responds to this by pointing out the obvious fact that women (or rather, people in general) are harmed by the practices within all sorts of industries. And once again this kind of harm ranges from the straightforwardly criminal to the subtle and psychological. Thus, there is no particular reason to single out pornography for special treatment in this regard: if there are laws or regulations being violated, then prosecutions should ensue; if there is psychological harm, counseling or more information should be provided so as to allow for informed choice; if financial necessity is forcing people to work in the industry when they would rather not, assistance should be given. In other words:

- (8) There are rights violations in all industries; there are ways of dealing with these problems other than through the banning of pornography.

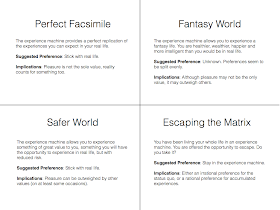

This allows us to provide the following argument map:

4. Concluding Thoughts

That brings us to the end of the discussion of Altman’s essay. I close with a couple of thoughts of my own. As I read through Altman’s piece, one question continued to gnaw at me: granting that there is some kind of right to pornography, does it follow that there should be open access to pornographic material?

The answer would appear to be an obvious “no”. And I certainly don’t think Altman thought any differently. The basic impression I got from him was that the current legal position is probably fine and that pornography should only be available to sexually mature adults. But I was struck by the possibility of more creative (and restrictive) forms of access. For instance, I toyed with the idea of a “pornography licence” which, much like how a gun licence operates in my own country, would only allow people who meet certain criteria to access pornography. I thought that, if there was a provable link between pornography and certain kinds of harm, this might be a reasonable compromise position.

But then another thought struck me: the internet has so revolutionised how we access information, and has made all kinds of information so easily available, that this would probably be impossible. And yet the fact that it is impossible to prevent a certain class of behaviours can't really be a good reason to stop trying to do so. The internet has also probably made it impossible to eliminate child pornography and terrorist conspiratorialising, but that doesn't mean we should stop trying to eliminate those things.