This post is the second part in my series on Stephen Maitzen's article "Ordinary Morality Implies Atheism". If you haven't read the first part, you really should.

1. The Core Argument

Part 1 presented the outline of Maitzen's argument. The logic of the argument is easy to grasp. It comes in two halves. The first argues that God's existence is incompatible with the existence of moral obligations; the second argues that ordinary morality requires the existence of moral obligations. These conclusions are incompatible, so something must give.

For most theists, the attachment to ordinary morality is significant: they do not want to say that we can stand idly by when great suffering is taking place. But neither do they wish to give up belief in God. As a result, they are likely to focus their critical faculties on the first bit of the argument, the "God implies no moral obligations"-bit. There must, they reason, be something wrong with that inference.

To see what that something might be, let's restate the core of this part of the argument (omitting some of the supplementary premises discussed in part 1).

- (1) God exists (or "I believe that God exists").

- (2) Necessarily, God only allows undeserved, involuntary suffering if it produces a net benefit for the sufferer (principle of Theodical Individualism).

- (3) Therefore, we never have an obligation to intervene to prevent suffering.

Obviously, (1) is immune to challenge by theists. So the problems, if they exist, must lie elsewhere. Indeed, we can distinguish two lines of attack: (i) argue that accepting the principle of Theodical Individualism (TI) does not absolve us of obligations to prevent suffering; or (ii) argue that we need not accept the principle of TI.

Maitzen considers a range of such objections, some more important than others. Let's go through them systematically (FYI: I'll be numbering the responses and counter-responses as I go along because I'm going to present an argument map at the end; in case you get confused the numbering builds on that already presented in part 1).

2. Does TI really imply the absence of moral obligations?

The first set of objections are happy with the principle of TI, but do not accept that this drains us of all sense of moral obligation. Two arguments are relevant here.

a. Strong Deontologism

The first I shall call "strong deontologism". This argues that our knowing that something will benefit someone does not absolve us of certain duties we may owe them. The following hypothetical scenario makes the point (taken from Maitzen's article):

The first I shall call "strong deontologism". This argues that our knowing that something will benefit someone does not absolve us of certain duties we may owe them. The following hypothetical scenario makes the point (taken from Maitzen's article):

Suppose I have promised to pay John $1,000 for some work he did for me, but I learn that John's uncle is about to leave him $1,000,000 on the condition that John doesn't have even $1,000 of his own. I inform John of this, but John, who hates his uncle and doesn't want anything from him, insists that I pay him as I promised to do.The strong deontologist would argue that in this situation our obligation to pay John survives our knowing he would otherwise receive a greater reward.

There are three things to be said in response to this. First, the obligation in the described scenario arises from the human institution of promising. Maitzen's argument relies on obligations to prevent suffering that do not arise from promises. Second, in the described scenario we might be able to see how John could be better off by rejecting the larger sum (damage, say, to self-respect). We usually don't have that ability when dealing with instances of great suffering. Third, a crucial aspect of the described scenario is John's volunteering to forego the money. It would be difficult to see how an obligation could survive if John did not volunteer to do this.

b. The "Stump" Response

The second argument comes from one of the chief theistic philosophers who tries to defend TI, Eleanore Stump. She makes two points. First, that God decides what is the appropriate amount of suffering for each individual. So all suffering is prima facie evil since we don't know how much is appropriate for the individual in question. Thus, we should try to eliminate any suffering we happen to come across. Her second point is that relieving a sufferer is likely to be beneficial to the character of the reliever.

Two comments are apposite here. First, at best, Stump has provided us with a permission to intervene, not an obligation to intervene. Second, he comment about the benefit to the character of the reliever is out of bounds: the whole point of TI is that the benefit must accrue to the person who suffers.

In sum, neither of these attempts to reconcile TI with the existence of moral obligations works. I'll summarise these arguments as follows:

- (8) Strong deontologism suggests that we can still owe duties to someone even when their observance makes the person worse off (John and his uncle example).

- (9) There are significant disanalogies between the case of John and his uncle, and the examples of obligations to intervene to prevent suffering: (a) it relies on the institution of promising; (b) we can imagine some greater benefit accruing to John; and (c) John volunteers to forego the money.

- (10) The Stump response: we still have a prima facie duty to intervene, and interventions probably improve the character of the intervener.

- (11) At best, Stump has provided us with a permission to intervene and her claim that the intervention might benefit the intervener is a contradiction of TI.

3. Is God Bound by TI?

We move on then to consider the second set of objections to Maitzen's argument. This set focuses on whether God is bound by the principle of TI. Three arguments arise suggesting he might not be: (i) in order to realise the good of libertarian free will he can abandon TI; (ii) heaven swamps everything; and (iii) according to some theologies, not even God has knowledge of the future.

i. Libertarian Free Will

As Maitzen notes, the idea that libertarian free will is a such an unqualified good that God might be justified in giving it to human beings, even though this may lead to great suffering, is a popular one. It is popular as an objection to the problem of evil and popular as an objection to the type of argument Maitzen is trying to make. Given its popularity, it is worth spending quite a bit of time discussing it.

Maitzen thinks the libertarian free will objection fails for three reasons: (a) libertarian free will is not an obviously coherent concept, nor the only morally valuable type of free will; (b) it is not clear that libertarian free will has a positive intrinsic moral value or that it is a value promoted by the God of the bible; and (c) ordinary moral practice, as embodied in the criminal law, does not seem concerned with libertarian free will. Let's go through each of these reasons at sufficient length.

a. The Coherence and Value of Free Will

As regards the coherence of libertarian free will, I would be willing to go quite a bit further than Maitzen: I would say that libertarian free will is almost certainly not a coherent concept. Allow me to explain.

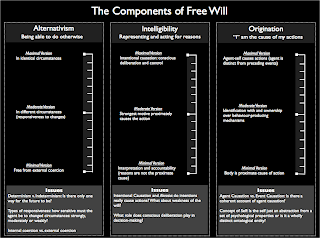

As Henrik Walter points out in his good, if poorly translated,* book The Neurophilosophy of Free Will, when people talk about "free will" they seem to be referring to a human capacity with three components: alternativism, intelligibility and origination.

By "alternativism" is meant the capacity to do otherwise than one actually did. So to say that we acted freely at some moment in the past, we must be able to say that it was possible for us to have made different decisions at those moments.

The alternativism-component of free will is subject to a number of interpretations, ranging from weak, to moderate, to strong. According to the strong interpretation, the capacity to do otherwise must hold even if circumstances were exactly the same; according to the weak interpretation, the capacity to do otherwise need only involve an ability to respond to different circumstances ("if things had been different, I would have done X").

By "intelligibility" is meant the capacity to represent and act for reasons. So it is not enough to say that we could have done otherwise, we must also be able to say that we acted for reason X, Y or Z.

Like alternativism, the intelligibility component of free will is subject to weak, moderate and strong interpretations. According to the strong interpretation, the reasons must be causally involved in the production of behaviour. This is what happens in the classical theory of intentional action. According to the weak interpretation, it is enough if the reasons and the behaviour have some common causal origin (as in Daniel Wegner's theory of the will).

By "origination" is meant that "you" are the cause of your decisions. In other words, it is not enough that intelligible decisions simply happen at random, they must be caused by a person or agent.

Again, like the other components, this component is open to weak, moderate and strong interpretations. According to the strong interpretation, actions must be caused by an ontologically unique entity known as the "agent". This agent is not reducible to causal psychological processes, it is something wholly distinct. According to the weak version, the agent is an abstraction from these psychological processes.

This component-view of free will is illustrated below (a heavily modified version of something found in Walter's book).

With that background in place, we can state simply the problem with the concept of libertarian free will: it holds to strong interpretations of all three components and it is not clear that this is possible.

Look at the origination component: libertarians want the agent to be the ultimate originator of action. It is no good, they will say, if actions are caused by preceding psychological states, because then we will need to ask about the causal history of those states, and before you know it you are caught in a problematic regress: it will seem as though "you" can never be responsible for your actions. But, if actions are not caused by underlying psychological processes, it is not at all clear that they can be intelligible in the strong sense.

Similar arguments apply to the strong interpretation of alternativism: libertarians want you do be able to otherwise than you did, in the exact same circumstances, but it appears that this type of alternativism would amount to arbitrariness. And arbitrariness would seem to defeat intelligibility and ultimate origination.

We could explore further problems, but the point is made.

Weaker accounts of free will are possible, and they are morally valuable. My own preferred version is an elaboration of the account developed by John Martin Fischer and Mark Ravizza in their book Responsibility and Control.

Their theory utilises weak to moderate versions of each component: all that is needed for moral accountability is that the mechanism producing human behaviour is capable of recognising and reacting to reasons, while at the same time being owned by a coherent personal narrative. They argue that this version can accommodate most of our ordinary moral practices.

b. Intrinsic Value and Biblical Support?

Maitzen's next argument against the libertarian objection is a two-parter. First he suggests, following Derk Pereboom, that libertarian free will does not have an intrinsic positive value. Pereboom's point is that in evaluating the morality of an evil action, the evildoer's freedom is a "weightless consideration". We don't say that Adolf Hitler's libertarian free will made his actions a little bit better than they would have been if they were pre-determined.

Second, the notion of libertarian free will as an intrinsic good that God cannot interfere with does not have biblical support. In two Bible passages (Exodus 14:8a and Romans 9:18) God "hardens hearts" and influences how people behave.

c. Libertarian Free Will is not a feature of Ordinary Moral Practices

Maitzen's final attack on the libertarian objection focuses on its absence from our ordinary moral practices. Here, we look to the operation of the criminal law (Anglo-American or Common Law versions) and see that libertarian free will is not a relevant consideration in the ascription of criminal responsibility.

Since Maitzen's claim intersects almost perfectly with my own area of research, I feel I can comment intelligently on it. On the whole, I think Maitzen is right: the criminal law is not interested in establishing that a defendant acted with libertarian free will. It is really only interested in establishing that the defendant was (and is) capable of recognising and responding to legal norms.

This is clearly illustrated by the operation of the defence of insanity. Legal insanity comes in two main varieties: cognitive and volitional. The cognitive version dominates in the US and was originally set out in the M'Naghten Rules. According to these rules, a defendant (even one with a recognised mental illness) will be held criminally liable unless they can show that at the time of the offence they did not know the nature and quality of the action they performed, or that it was legally wrong.

The volitional standard is not that popular anymore, although it is used my home country. It holds that a defendant will not be held responsible if they suffered from an "irresistible impulse" at the time of the offence. This might, on its surface, appear to be a concession to the libertarian position, but it isn't. What is meant by "irresistible impulse" is an impulse that does not respond to the presence of legal norms. Responsiveness of this sort does not depend on libertarian free will.

Of course, there has been plenty of controversy in this area. Many have tried, over the past two centuries at least, to argue that criminal responsibility makes no sense without libertarian free will, and since libertarian free will is wrong, we should abandon the traditional system of criminal justice. I think what is remarkable is that, despite occasional flip-flopping, the system of criminal justice has repeatedly rejected these arguments.

A good, if somewhat dated, article covering these issues is here (subscription required).

So to sum up: the libertarian free will objection is not successful.

ii. Heaven Swamps Everything

A second suggestion is that heaven is so wonderful that it manages to compensate people for any suffering they might experience in life, even if that suffering is in no way necessary for attaining the reward (which it isn't if we stick to the original definition of TI).

So the victims of systematic child abuse could undergo undeserved and involuntary suffering that is not necessary in order for them to achieve a heavenly reward. Nonetheless, the fact that they may ultimately receive that reward would compensate them for their suffering. Indeed, we might even say that because the reward is so great, people are likely to retrospectively consent to whatever suffering they endured.

Maitzen argues that not only does this conflate compensation with justification, it would also seem to erode any sense of moral obligation. Again, ordinary moral practice would not deem child abuse less worthy of condemnation and prevention if the children who suffered it retrospectively consented to it.

iii. Open Theism

The final objection comes from a branch of theology that deems it impossible for God to hold to TI. Why? Because not even God has knowledge of that part of the future that is dependent on the libertarian free choices of human beings.

Three responses are apposite. First, we have already seen that libertarian free will is not an obviously coherent concept. Second, God is still likely to have more foreknowledge than anyone else. So he would still prevent suffering that is highly unlikely to produce a net benefit. Third, if these objections fail, we could concede that the argument being made is only relevant to classical theism.

Okay, so that's everything. Let's summarise the arguments presented here and plug them into an argument map.

*I base that purely on my reading of the English version, which seems somewhat stilted. Perhaps it was like that in the original German. It is also worth noting that the three-component take on free will is not original to Walter.

i. Libertarian Free Will

As Maitzen notes, the idea that libertarian free will is a such an unqualified good that God might be justified in giving it to human beings, even though this may lead to great suffering, is a popular one. It is popular as an objection to the problem of evil and popular as an objection to the type of argument Maitzen is trying to make. Given its popularity, it is worth spending quite a bit of time discussing it.

Maitzen thinks the libertarian free will objection fails for three reasons: (a) libertarian free will is not an obviously coherent concept, nor the only morally valuable type of free will; (b) it is not clear that libertarian free will has a positive intrinsic moral value or that it is a value promoted by the God of the bible; and (c) ordinary moral practice, as embodied in the criminal law, does not seem concerned with libertarian free will. Let's go through each of these reasons at sufficient length.

a. The Coherence and Value of Free Will

As regards the coherence of libertarian free will, I would be willing to go quite a bit further than Maitzen: I would say that libertarian free will is almost certainly not a coherent concept. Allow me to explain.

As Henrik Walter points out in his good, if poorly translated,* book The Neurophilosophy of Free Will, when people talk about "free will" they seem to be referring to a human capacity with three components: alternativism, intelligibility and origination.

By "alternativism" is meant the capacity to do otherwise than one actually did. So to say that we acted freely at some moment in the past, we must be able to say that it was possible for us to have made different decisions at those moments.

The alternativism-component of free will is subject to a number of interpretations, ranging from weak, to moderate, to strong. According to the strong interpretation, the capacity to do otherwise must hold even if circumstances were exactly the same; according to the weak interpretation, the capacity to do otherwise need only involve an ability to respond to different circumstances ("if things had been different, I would have done X").

By "intelligibility" is meant the capacity to represent and act for reasons. So it is not enough to say that we could have done otherwise, we must also be able to say that we acted for reason X, Y or Z.

Like alternativism, the intelligibility component of free will is subject to weak, moderate and strong interpretations. According to the strong interpretation, the reasons must be causally involved in the production of behaviour. This is what happens in the classical theory of intentional action. According to the weak interpretation, it is enough if the reasons and the behaviour have some common causal origin (as in Daniel Wegner's theory of the will).

By "origination" is meant that "you" are the cause of your decisions. In other words, it is not enough that intelligible decisions simply happen at random, they must be caused by a person or agent.

Again, like the other components, this component is open to weak, moderate and strong interpretations. According to the strong interpretation, actions must be caused by an ontologically unique entity known as the "agent". This agent is not reducible to causal psychological processes, it is something wholly distinct. According to the weak version, the agent is an abstraction from these psychological processes.

This component-view of free will is illustrated below (a heavily modified version of something found in Walter's book).

With that background in place, we can state simply the problem with the concept of libertarian free will: it holds to strong interpretations of all three components and it is not clear that this is possible.

Look at the origination component: libertarians want the agent to be the ultimate originator of action. It is no good, they will say, if actions are caused by preceding psychological states, because then we will need to ask about the causal history of those states, and before you know it you are caught in a problematic regress: it will seem as though "you" can never be responsible for your actions. But, if actions are not caused by underlying psychological processes, it is not at all clear that they can be intelligible in the strong sense.

Similar arguments apply to the strong interpretation of alternativism: libertarians want you do be able to otherwise than you did, in the exact same circumstances, but it appears that this type of alternativism would amount to arbitrariness. And arbitrariness would seem to defeat intelligibility and ultimate origination.

We could explore further problems, but the point is made.

Weaker accounts of free will are possible, and they are morally valuable. My own preferred version is an elaboration of the account developed by John Martin Fischer and Mark Ravizza in their book Responsibility and Control.

Their theory utilises weak to moderate versions of each component: all that is needed for moral accountability is that the mechanism producing human behaviour is capable of recognising and reacting to reasons, while at the same time being owned by a coherent personal narrative. They argue that this version can accommodate most of our ordinary moral practices.

b. Intrinsic Value and Biblical Support?

Maitzen's next argument against the libertarian objection is a two-parter. First he suggests, following Derk Pereboom, that libertarian free will does not have an intrinsic positive value. Pereboom's point is that in evaluating the morality of an evil action, the evildoer's freedom is a "weightless consideration". We don't say that Adolf Hitler's libertarian free will made his actions a little bit better than they would have been if they were pre-determined.

Second, the notion of libertarian free will as an intrinsic good that God cannot interfere with does not have biblical support. In two Bible passages (Exodus 14:8a and Romans 9:18) God "hardens hearts" and influences how people behave.

c. Libertarian Free Will is not a feature of Ordinary Moral Practices

Maitzen's final attack on the libertarian objection focuses on its absence from our ordinary moral practices. Here, we look to the operation of the criminal law (Anglo-American or Common Law versions) and see that libertarian free will is not a relevant consideration in the ascription of criminal responsibility.

Since Maitzen's claim intersects almost perfectly with my own area of research, I feel I can comment intelligently on it. On the whole, I think Maitzen is right: the criminal law is not interested in establishing that a defendant acted with libertarian free will. It is really only interested in establishing that the defendant was (and is) capable of recognising and responding to legal norms.

This is clearly illustrated by the operation of the defence of insanity. Legal insanity comes in two main varieties: cognitive and volitional. The cognitive version dominates in the US and was originally set out in the M'Naghten Rules. According to these rules, a defendant (even one with a recognised mental illness) will be held criminally liable unless they can show that at the time of the offence they did not know the nature and quality of the action they performed, or that it was legally wrong.

The volitional standard is not that popular anymore, although it is used my home country. It holds that a defendant will not be held responsible if they suffered from an "irresistible impulse" at the time of the offence. This might, on its surface, appear to be a concession to the libertarian position, but it isn't. What is meant by "irresistible impulse" is an impulse that does not respond to the presence of legal norms. Responsiveness of this sort does not depend on libertarian free will.

Of course, there has been plenty of controversy in this area. Many have tried, over the past two centuries at least, to argue that criminal responsibility makes no sense without libertarian free will, and since libertarian free will is wrong, we should abandon the traditional system of criminal justice. I think what is remarkable is that, despite occasional flip-flopping, the system of criminal justice has repeatedly rejected these arguments.

A good, if somewhat dated, article covering these issues is here (subscription required).

So to sum up: the libertarian free will objection is not successful.

ii. Heaven Swamps Everything

A second suggestion is that heaven is so wonderful that it manages to compensate people for any suffering they might experience in life, even if that suffering is in no way necessary for attaining the reward (which it isn't if we stick to the original definition of TI).

So the victims of systematic child abuse could undergo undeserved and involuntary suffering that is not necessary in order for them to achieve a heavenly reward. Nonetheless, the fact that they may ultimately receive that reward would compensate them for their suffering. Indeed, we might even say that because the reward is so great, people are likely to retrospectively consent to whatever suffering they endured.

Maitzen argues that not only does this conflate compensation with justification, it would also seem to erode any sense of moral obligation. Again, ordinary moral practice would not deem child abuse less worthy of condemnation and prevention if the children who suffered it retrospectively consented to it.

iii. Open Theism

The final objection comes from a branch of theology that deems it impossible for God to hold to TI. Why? Because not even God has knowledge of that part of the future that is dependent on the libertarian free choices of human beings.

Three responses are apposite. First, we have already seen that libertarian free will is not an obviously coherent concept. Second, God is still likely to have more foreknowledge than anyone else. So he would still prevent suffering that is highly unlikely to produce a net benefit. Third, if these objections fail, we could concede that the argument being made is only relevant to classical theism.

Okay, so that's everything. Let's summarise the arguments presented here and plug them into an argument map.

- (12) God can break TI in order to realise the good of libertarian free will.

- (13) Heaven Swamps Everything.

- (14) God cannot hold to TI because not even God has perfect knowledge of the future.

- (15) Libertarian free will is not obviously coherent.

- (16) Libertarian free will has no intrinsic moral value and is not biblically supported.

- (17) Libertarian free will is not relied upon by ordinary moral practices.

- (18) Heaven swamps everything confuses compensation with justification. Furthermore, retrospective consent cannot justify evil.

- (19) Three objections to open theism: (a) libertarian free will is not obviously coherent; (b) God would have more foreknowledge than anyone else and so would adhere to TI as best he could; and (c) perhaps Maitzen's argument is only relevant to classical theism.

*I base that purely on my reading of the English version, which seems somewhat stilted. Perhaps it was like that in the original German. It is also worth noting that the three-component take on free will is not original to Walter.

Another phenomenal post. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteJohn D,

ReplyDeleteMany thanks for such a thorough exposition and analysis of my argument. I learned a lot from it, especially your discussion of criminal law, and I'll be sure to read the law review article you linked to. I'd make just one tweak to your post. You paraphrase me as saying "unnecessary suffering cannot be justified simply because it is retrospectively consented to." I'm not sure that the victim's retrospective consent can't ever justify the treatment he suffered (and can, at most, only excuse it). I'm willing to grant that retrospective consent might justify, but in that case (as I said in the article) I think our moral obligation to prevent the suffering disappears: we're not obligated to prevent suffering that (we know) the victim will on due reflection always consent to. So even if heaven not only swamps but justifies everything, our ordinary moral obligation to prevent suffering goes by the boards.

Thanks for a very illuminating post. I found the discussion of free will particularly educating.

ReplyDeleteI fail to see why only libertanian free will can justify god's abandoning TI - why can't weaker free will variants suffice? Ones that are coherent, applicable, and so on. God basically allows undeserved suffering as a necessary evil in order to allow humans moral choices; surely there would be no denying that people can make moral choices. This eliminates (15) and (17); (16) can be eliminated by referring to all the cases the bible does give significance to the choices of the elect (i.e. Israel), and insisting that free will is a prerequisite for moral value even if it is not of value by itself. Thus we retain (12), allowing it to successfully undermine (2).

Now, I would argue that accepting this weaker (12) is unreasonable (it is unreasonable to allow a person to kill freely to preserve his free will), but that's another line of argument. Indeed, all this discussion amounts to theodicity. That's a whole can of worms. Personally, I don't think TI, TI except free-will, or any other single-world solution to the problem of evil works. But I'm trying to focus on the line of argument raised in the posts/article.

Yair Rezek

Yair,

ReplyDeleteFirst off, I would say that Steve is responding to typical theistic objections which do emphasise the importance of libertarian free will.

However, the point you raise is an interesting one. You are saying that a non-libertarian version of free will, let's say one based on deterministic counterfactual reasoning, would allow for meaningful moral choice. I agree.

But then if we make that concession, I can't see why God couldn't have made it the case that we engage in deterministic counterfactual reasoning that never leads suffering. In other words, we engage in a processing of practical reasoning; during that process we imagine possible worlds in which our actions lead to great suffering; but we never attempt to realise these possible worlds.

To avoid this, we would have to fall back on libertarian free will, which fails for the reasons stated above.

For those who may be interested, Jerome Gellman’s critique of my article will soon appear in EJPR, along with my reply, which is available here. I don’t think I’m authorized to post Gellman’s article as well, but my reply quotes it at length and, I believe, captures the debate between us.

ReplyDelete