Friday, August 20, 2010

Episode 6 - The Absurd

The sixth episode of the podcast is available for download here. In this episode, I compare and contrast the views of Thomas Nagel and William Lane Craig on the absurdity of life. Prepare to embrace absurdity with a little bit of irony.

Apparently, the practice of hat-tipping is part of accepted internet etiquette. I therefore duly doff my cap in the direction of Steve Maitzen who gave me the idea for this one.

You can subscribe to the podcast on iTunes.

Sunday, August 15, 2010

Episode 5 - Transcendence Without God

Episode 5 of the podcast is available for download here. In this episode, I discuss the article "Transcendence without God" by Anthony Simon Laden. The essay appears in the collection Philosophers Without Gods.

Not much to say about this one -- apart from what is said in the podcast itself.

Friday, August 13, 2010

Interruption to "Normal" Services

So after a flurry of blogging activity in the past week, I regret to inform you all that I will be on a blogging hiatus for the next three weeks. This is partly due to the need to take some sort of summer holiday and partly due to the need to focus on my own research work.

On the plus side, I have a couple of podcasts recorded and I will schedule them for appearance over the coming week.

You can still post comments of course, and I may even respond to some of them, but don't expect any substantive posts until September.

Over and out.

JD

P.S. - I think I would like to grow the readership of this blog. I currently only get about 50 people per day, which is a small drop in the large ocean of internet-users. Obviously, I need to do some work of my own to promote. But if you like what you read here, it would be nice if you could share it or link to it on other blogs and forums that you frequent. I know that a number of readers already do that and I would like to take this opportunity to thank them for it.

On the plus side, I have a couple of podcasts recorded and I will schedule them for appearance over the coming week.

You can still post comments of course, and I may even respond to some of them, but don't expect any substantive posts until September.

Over and out.

JD

P.S. - I think I would like to grow the readership of this blog. I currently only get about 50 people per day, which is a small drop in the large ocean of internet-users. Obviously, I need to do some work of my own to promote. But if you like what you read here, it would be nice if you could share it or link to it on other blogs and forums that you frequent. I know that a number of readers already do that and I would like to take this opportunity to thank them for it.

Enoch on The Epistemological Challenge to Metanormative Realism (Part 3)

|

| David Enoch, on the left |

This post is part of a short series on David Enoch's article "The Epistemological Challenge to Metanormative Realism". Parts one and two are available here and here.

In the previous part, we outlined the precise nature of the epistemological challenge facing non-natural ("Robust") moral realists. We can briefly restate it as follows:

- Robust realists think that there is some coincidence between our moral beliefs and moral truth. They owe us some explanation of how this could be the case given that, by their own lights, moral truths are independent of our judgments and are causally inert.

In this part, we will see how Enoch responds to the challenge.

He starts with some methodological points.

1. The Plausibility Game

As outlined above, the challenge is an explanatory one. But there is a problem with this: there could be brute, unexplainable facts. There is certainly no obvious logical contradiction in the notion of a brute fact. Given this possibility, robust realism's lack of an explanation for the coincidence simply deducts a few plausibility points from the overall theory. It may still win the plausibility game.

That said, robust realists shouldn't shirk the challenge. If they can provide an explanation, and if their theory is more plausible than alternatives, it would be all the better. And when looking for an explanation we follow the standard rules of the explanation game: we try to satisfy a set of explanatory criteria and we compare and contrast competing explanations.

Three additional points need to be made about the kind of explanation we are looking for.

First, Enoch thinks that it is important to bear in mind that the coincidence between our moral beliefs and moral truth is not all that striking. No moral realist thinks that we always get things right or that our intuitions are infallible. They would agree that sound moral reasoning requires special training and sensitivities. (Note that the same is true for mathematical Platonists.) And because the correlation is weak, a relatively weak explanation is all that is required.

Second, we must accept the possibility that an fallible reasoning mechanism could become more refined and accurate in its judgments over time, e.g. by eliminating inconsistencies, increasing coherence, drawing analogies and so on. There could even be some evolutionary story about how, say, the more primitive primate reasoning mechanism was refined into the more sophisticated homo sapiens mechanism. Could the same not be true of the portion of the reasoning mechanism responsible for moral judgments?

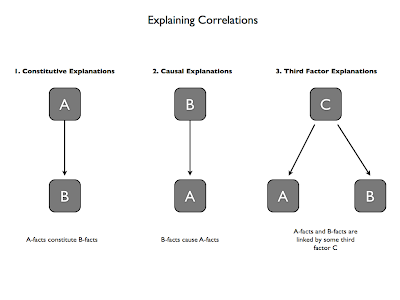

Third, there are two traditional ways to explain a correlation between two sets of facts. First, we can say that all B-facts are constituted by A-facts. Second, we can say that all B-facts are (causally) responsible for A-facts. Obviously, neither of these approaches is an option when it comes to robust realism.

However, there is another possibility: a third factor explanation. In other words, an explanation that shows how A-facts and B-facts are linked by a third factor C that is responsible for both A-facts and B-facts. Pre-established harmony explanations are of this sort, and Enoch wants to offer a pre-established harmony explanation for the troubling coincidence.

2. Survival as a Moral Good

Enoch's explanation is roughly as follows.

Let's begin with some assumptions about what is or is not a moral good (or, more generally, a moral truth). For example, let's assume that pain is morally bad and pleasure is morally good (not always and everywhere, but for the most part). Let's further assume that survival and reproduction are, in some sense, moral goods. This may be because they are correlated with the more basic moral good of pain.

This is not a strong assumption. Survival and reproduction do not trump all other moral goods, but they are usually better than the alternatives (death and infertility), in an all-things-considered sort of way.

Now, obviously, survival and reproduction are the key selection pressures in evolutionary history. So it would be unsurprising to find that evolved beings like ourselves have beliefs and desires that were correlated with them.

But since those selection pressures are in turn correlated with some moral truths (namely, that survival and reproduction are moral goods) we have an explanation of the puzzling coincidence between our normative beliefs and the mind-independent, causally inert moral truth.

In other words, what is evolutionarily beneficial has pre-established harmony with what is morally good, and what is evolutionarily beneficial causally shapes our cognitive faculties. This is, in effect, an inversion of Street's Darwinian Dilemma. It shows how robust realists have nothing to fear from evolutionary processes.

While you are digesting all of this, bear in mind that Enoch does not think that the correlation that needs to be explained is particularly impressive. So it does not matter if survival is not a primary or essential moral good. All that matters is that there is some slight correlation between normative beliefs and moral truths.

3. Too Good to be True?

Isn't this explanation just a little too convenient? Isn't there something fishy about it? For starters, why think that survival is a moral good?

Enoch offers a few responses. First, as noted above, it may be because it is itself correlated with other more basic moral goods, such as the absence of pain. Second, it may be true that some creatures are particularly evil and their continued existed would be bad. That, he thinks, does not really matter. As long as survival is good for creatures like us -- even if only because it makes other moral goods possible -- it is enough.

Maybe it is, but even so, hasn't Enoch just replaced one puzzling coincidence with another? I mean, isn't it somehow miraculous that evolutionary selection pressures just happened to align themselves with moral truths? This is a problem arising from the lack of counterfactual robustness inherent in Enoch's explanation: if things had been different...

Again, Enoch has a few responses. First, it is not clear that things could have been different. Could evolutionary processes really have aimed at something other than survival and reproduction?

Second, Enoch thinks it significant that he has reduced several puzzling coincidences -- between different normative beliefs and different moral truths -- to just one puzzling coincidence -- between the central evolutionary aim and a moral good. In the context of the plausibility game outlined above, this helps to raise realism's attractiveness.

Finally, brute luck is surely lurks behind other cognitive faculties that are shaped by evolutionary forces, e.g. those used in mathematical reasoning. So there is a level playing field when it comes to this issue.

Third, there are two traditional ways to explain a correlation between two sets of facts. First, we can say that all B-facts are constituted by A-facts. Second, we can say that all B-facts are (causally) responsible for A-facts. Obviously, neither of these approaches is an option when it comes to robust realism.

However, there is another possibility: a third factor explanation. In other words, an explanation that shows how A-facts and B-facts are linked by a third factor C that is responsible for both A-facts and B-facts. Pre-established harmony explanations are of this sort, and Enoch wants to offer a pre-established harmony explanation for the troubling coincidence.

Enoch's explanation is roughly as follows.

Let's begin with some assumptions about what is or is not a moral good (or, more generally, a moral truth). For example, let's assume that pain is morally bad and pleasure is morally good (not always and everywhere, but for the most part). Let's further assume that survival and reproduction are, in some sense, moral goods. This may be because they are correlated with the more basic moral good of pain.

This is not a strong assumption. Survival and reproduction do not trump all other moral goods, but they are usually better than the alternatives (death and infertility), in an all-things-considered sort of way.

Now, obviously, survival and reproduction are the key selection pressures in evolutionary history. So it would be unsurprising to find that evolved beings like ourselves have beliefs and desires that were correlated with them.

But since those selection pressures are in turn correlated with some moral truths (namely, that survival and reproduction are moral goods) we have an explanation of the puzzling coincidence between our normative beliefs and the mind-independent, causally inert moral truth.

In other words, what is evolutionarily beneficial has pre-established harmony with what is morally good, and what is evolutionarily beneficial causally shapes our cognitive faculties. This is, in effect, an inversion of Street's Darwinian Dilemma. It shows how robust realists have nothing to fear from evolutionary processes.

While you are digesting all of this, bear in mind that Enoch does not think that the correlation that needs to be explained is particularly impressive. So it does not matter if survival is not a primary or essential moral good. All that matters is that there is some slight correlation between normative beliefs and moral truths.

3. Too Good to be True?

Isn't this explanation just a little too convenient? Isn't there something fishy about it? For starters, why think that survival is a moral good?

Enoch offers a few responses. First, as noted above, it may be because it is itself correlated with other more basic moral goods, such as the absence of pain. Second, it may be true that some creatures are particularly evil and their continued existed would be bad. That, he thinks, does not really matter. As long as survival is good for creatures like us -- even if only because it makes other moral goods possible -- it is enough.

Maybe it is, but even so, hasn't Enoch just replaced one puzzling coincidence with another? I mean, isn't it somehow miraculous that evolutionary selection pressures just happened to align themselves with moral truths? This is a problem arising from the lack of counterfactual robustness inherent in Enoch's explanation: if things had been different...

Again, Enoch has a few responses. First, it is not clear that things could have been different. Could evolutionary processes really have aimed at something other than survival and reproduction?

Second, Enoch thinks it significant that he has reduced several puzzling coincidences -- between different normative beliefs and different moral truths -- to just one puzzling coincidence -- between the central evolutionary aim and a moral good. In the context of the plausibility game outlined above, this helps to raise realism's attractiveness.

Finally, brute luck is surely lurks behind other cognitive faculties that are shaped by evolutionary forces, e.g. those used in mathematical reasoning. So there is a level playing field when it comes to this issue.

4. Concluding Thoughts

So that's it; that's Enoch's solution to the epistemological challenge. He agrees that there are still concerns, but thinks his response can help to increase the plausibility of robust realism. In the final section of his article, he considers whether his solution could generalise to other contexts in which similar epistemological challenges are faced.

Unfortunately, he doesn't say very much. He says that its generalisability will depend on whether an analogue of the "goodness of evolutionary aims" can be found in other domains.

Maybe I can say a few words. As noted in part two, mathematical Platonism is the other theory that clearly faces a similar challenge. But, in some ways, I think the challenge may be easier to meet in that domain than it is in the case of morality.

Why do I think this? Well, I suppose I have in mind the fact that physical reality seems to be structured in a mathematical way. This is certainly the assumption underlying the science of physics. And since we have causal interactions with that physical reality, the fact that our mathematical beliefs line-up with mathematical truth is not particularly surprising.

Now there are gaps in this explanation. Certainly, the more abstruse aspects of number theory may have little connection with the physical structure of reality (I'll have to plead ignorance here). But that's not too worrying since, as Enoch noted, the correlation is relatively weak: not everyone is a good mathematician.

The question we need to consider is whether the response to the challenge in the case of mathematical Platonism is any better or worse than Enoch's response? It might be better in that the fact that evolutionary processes are subject to mathematical physical laws is less surprising than the fact (if it is a fact) that they are subject to moral laws. I certainly find the latter to be odder than the former, although I can't articulate the reason for my discomfort.

On the other hand, it may just be that I have found the analogy Enoch was alluding to.

Any thoughts?

Thursday, August 12, 2010

Enoch on The Epistemological Challenge to Metanormative Realism (Part 2)

|

| David Enoch, on the left |

This post is part of a brief series on David Enoch's article "The Epistemological Challenge to Metanormative Realism". Part one is here.

The epistemological challenge in question is roughly the following: non-natural moral realists (or Robust Realists) owe us some account of how our moral beliefs could be true, given the abstract nature of moral properties. The goal of Enoch's article is to give the best possible articulation of this challenge and then respond to it from a robust realist perspective.

In part one, we went through how not to think about the challenge. At the end, we came up with a list of desiderata for a good version of the epistemological challenge. I would invite you to check back on those before reading the remainder of this entry, which is going to present a "good" version of the challenge.

1. The Epistemological Challenge Formulated

Enoch begins by asking us to imagine the following case. Bill has beliefs about a remote village in Nepal. As it happens, most of Bill's beliefs about the village are true. In other words, there is a coincidence between Bill's beliefs and the truth-about-the-village.

Surely this coincidence must be explained? Enoch thinks so. And he thinks the route to a satisfactory explanation is well-known: we tell some causal story about how Bill got his true beliefs. So, for example, either he lived in the village for a period of time, or he knew somebody who lived there, or he read some accurate account of it.

Using this example, some have presented the following problem for mathematical Platonists. The Platonist thinks that mathematical truths are abstract and mind-independent. Nevertheless, they also think that mathematicians can have true beliefs about this abstract domain. But how did this happen? How did the true beliefs get into the mathematicians head?

There is no easy answer for the Platonist. They do not think that the mathematician's judgments constitute or create mathematical truth; they think mathematical truth is mind-independent. Nor do they think that mathematical truths have causal properties; indeed, they think they are causally inert.

So the coincidence seems too good to be true. Notice how the exact same problem faces the Robust moral realist. They think we can have true moral beliefs, but they do not think (i) that moral truths have causal properties; or (ii) that moral truths are constituted by our judgments.

This, then, is the epistemological challenge.

2. Some Comments

This version of the challenge meets the criteria set down in part one. First, because it is not expressed in terms of other controversial epistemological concepts such as "access", "justification" or "knowledge".

Second, because it is not applicable to other metaethical theories. Naturalistic moral realists can sidestep the challenge by granting that moral truths have causal properties. And antirealist positions -- such as constructivism -- can sidestep the challenge by claiming that moral truths are constituted by our own judgments.

The challenge does touch upon the externalist/internalist debate in contemporary epistemology. It is very clearly about the external conditions of knowledge, i.e. the external conditions that must be met in order for us to have reliable, truth-apt cognitive faculties.

Because it is about these external conditions, a robust realist might think they can avoid the challenge by sticking with an internalist account of justification. In other words, by showing how their moral beliefs have been soundly deduced or inferred from other more foundational beliefs.

Enoch doesn't think this will work. Why? Because once doubt has been raised about the reliability of the external conditions of belief-formation, there is a defeater for the internal account of justification. So the realist cannot avoid the challenge.

And the problem for Enoch is that -- as of when he was writing -- no realist had dealt with the challenge. He wanted to fix that.

3. Street's Darwinian Dilemma

Before moving on to his own solution to the challenge, Enoch notes that Sharon Street's Darwinian Dilemma -- which I've covered in abbreviated form -- is a particular version of the challenge he has formulated.

Briefly, Street says that a realist must think that evolutionary processes just happened to stumble upon cognitive faculties that were attuned to a causally inert moral reality. This is clearly implausible since evolutionary processes are causal through-and-through.

Okay that's it for now. In the next part we will see how Enoch responds to the epistemological challenge.

Omnipotence (Part 4)

This post is part of my series on Nicholas Everitt's book The Non-Existence of God. For an index, see here.

I am currently working through Chapter 13 of the book. This chapter deals with the potential contradictions inherent in the concept of an omnipotent being. Everitt surveys five possible definitions of omnipotence and checks them for inconsistencies.

We closed the last part by looking at the third definition of omnipotence:

- Def. 3: "X is omnipotent" = "X can do everything that it is logically possible for a being with X's defining or necessary properties to do."

Applied to God, this definition means that God's power must be consistent with his freedom, knowledge and moral perfection. In a different series of posts, we ran into some of the problems with this definition.

Everitt raises similar objections.

1. God's Omnipotence is Relative to Time

Some things are only logically possible at particular moments in time. If we assume that God is in some sense temporal (either totally or just in his relations with human beings) then his power would limited by ordinary temporal processes. For example, it would have been possible for him to prevent the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami back in 2004, but not in 2006.

If this reasoning is correct, we get a fourth definition of omnipotence:

- Def. 4: "X is omnipotent" = "At every time, X can do everything that it is logically possible for a being of X's nature to do at that time."

So now God's power is relativised to both his nature and to time. Does this leave us with a coherent conception of omnipotence?

Not really, as Everitt notes, once you start relativising your definition of omnipotence in this manner you open up the possibility of many omnipotent beings. Indeed, every being is omnipotent relative to some identifiable set of constraints. This would seem to make a mockery of the notion of an all-powerful being. (This was discussed previously)

The mockery becomes apparent if we consider the following reductio.

- A Nullipotent being = A being, one of whose defining properties is the inability to do anything

This being would count as omnipotent, if we were to follow definitions 3 and 4. This is clearly absurd. So those definitions must be inadequate.

2. A Final Possibility

What can the theist do to avoid this absurdity? Everitt considers one final definition:

- Def. 5: "X is omnipotent" = "At every time, X can do everything which it is logically possible for a being of X's nature to do at that time; and no being, Y, greater in overall power than X, can be conceived."

The final clause seems to avoid the absurdity of the nullipotent being, but it does so at the expense of creating further problems with the concept of omnipotence.

First, there is the measurement problem. The definition assumes that we have some readily-available metric for comparing the relative strengths of the capacities possessed by different beings. This might be true if all beings could obtain the same capacities (e.g. X, Y, Z) and one being had more or less of them. But if beings have distinct sets of capacities, e.g. {X, Y, Z} vs. {R, S, T} commensurability becomes an issue.

Second, and more seriously, it would imply that God, as traditionally conceived, is not omnipotent. To see this, compare God with Semigod. God has all the traditional divine properties. He is morally perfect, all-knowing, all-present, and so on. Semigod has all the traditional properties save one: he is not morally perfect. God, due to his moral perfection, could not commit a morally evil act; Semigod could. It would then follow, from definition 5, that Semigod is omnipotent and God is not.

One doubts whether that would be palatable to a traditional theist.

3. Conclusion

What have we learned from this exploration of omnipotence? Clearly, we have learned that omnipotence is a tricky concept. The most natural definition -- Definition Two -- becomes problematic when applied to a being who fits with the traditional conception of God. And the subsequent "relativised" definitions seem to lead to absurdities or to the unappetising conclusion that God is not omnipotent.

The one possible solution -- canvassed in part three -- would be to develop a sound argument for a logically necessary God. This would be a version of the ontological argument. Whether such an argument is possible is a question for another day.

In the meantime, the following diagram summarises the five definitions of omnipotence covered in this series, as well as some of the problems associated with them.

Omnipotence (Part 3)

This post is part of my series on Nicholas Everitt's book The Non-Existence of God. For an index, see here.

I am currently working my way through Chapter 13 of the book. This chapter deals with the potential contradictions inherent in the concept of an omnipotent being. Everitt looks at five separate definitions of omnipotence and checks them for consistencies.

We are currently looking at the second, and most popular definition of omnipotence:

- Def. 2 "X is Omnipotence" = "X can do everything that is logically possible."

As noted, this definition throws up certain problems for God because there are things that we physical, fallible, and mortal human beings can do that would not seem to be possible for an immaterial, perfect and immortal being like God. For instance, we can perform morally corrupt acts; we can eat, sleep, run, walk and so on -- all activities requiring a physical body; and, finally, we can bring about our own annihilation (suicide). God, it would seem, could not do any of this.

In part two we looked at the possibility of a sinful God and found it to be theologically circumspect. In this post we will look at God's lack of a physical body and his potential suicide. We then move on to consider a third definition of omnipotence.

1. God's physical body

Is the claim that God cannot do anything that requires a physical body a serious objection to his omnipotence? For many religious believers, including orthodox Christians, it isn't. For them, there is an easy way for God to perform actions requiring a physical body: he can occasionally take physical form.

Indeed, according to Christianity that's exactly what he did when he killed himself on the cross to satisfy his own sense of justice (or something like that!).

Everitt thinks that there might be a problem with this type of response to the original objection. When we perform an action such as scratching our noses, we are identical with the person doing the scratching. God would not have that kind of identity-relationship with a physical form. After all, God didn't actually die when Jesus died on the cross.

Or did he? This gets us into a theological minefield and I'm not sure that any coherent thought can survive passing through it. Maybe that is itself good grounds for the incoherence of the traditional Christian conception of God.

Whatever else it provides a neat segue to the next section.

2. Can God Kill Himself?

If God cannot kill himself then there is something that is logically possible but not in his power to do. And surely it must be true that God cannot kill himself. In the previous part, it was suggested that God could do things that would make him lose certain divine properties. That's problematic in itself, but we are now asking whether God could bring about his own total annihilation.

Theists have a way out of this, but it isn't pretty. They can argue that God is a logically necessary being, i.e. that his non-existence is logically impossible. And since Definition 2 only claims that God can do whatever it is logically possible to do, the crisis is averted.

The ugly part of this response is that it forces the theist to accept a fairly strong form of the ontological argument. This is the only argument that makes God a logically necessary being (some versions of the cosmological argument might make God physically or metaphysically necessary, but that's not the same thing -- we need an argument that makes his non-existence logically contradictory).

Since the ontological argument is highly contentious, and unpersuasive to many theists, the objection is likely to stand.

3. Relativised Omnipotence

The conclusion from the above (and from part two) is roughly the following: unless one is willing to embrace some pretty weird doctrines about God (that he could perform some actions that would make him lose divine properties) or the ontological argument, God cannot do everything that it is logically possible to do.

This provides the impetus for a third definition of omnipotence:

1. God's physical body

Is the claim that God cannot do anything that requires a physical body a serious objection to his omnipotence? For many religious believers, including orthodox Christians, it isn't. For them, there is an easy way for God to perform actions requiring a physical body: he can occasionally take physical form.

Indeed, according to Christianity that's exactly what he did when he killed himself on the cross to satisfy his own sense of justice (or something like that!).

Everitt thinks that there might be a problem with this type of response to the original objection. When we perform an action such as scratching our noses, we are identical with the person doing the scratching. God would not have that kind of identity-relationship with a physical form. After all, God didn't actually die when Jesus died on the cross.

Or did he? This gets us into a theological minefield and I'm not sure that any coherent thought can survive passing through it. Maybe that is itself good grounds for the incoherence of the traditional Christian conception of God.

Whatever else it provides a neat segue to the next section.

2. Can God Kill Himself?

If God cannot kill himself then there is something that is logically possible but not in his power to do. And surely it must be true that God cannot kill himself. In the previous part, it was suggested that God could do things that would make him lose certain divine properties. That's problematic in itself, but we are now asking whether God could bring about his own total annihilation.

Theists have a way out of this, but it isn't pretty. They can argue that God is a logically necessary being, i.e. that his non-existence is logically impossible. And since Definition 2 only claims that God can do whatever it is logically possible to do, the crisis is averted.

The ugly part of this response is that it forces the theist to accept a fairly strong form of the ontological argument. This is the only argument that makes God a logically necessary being (some versions of the cosmological argument might make God physically or metaphysically necessary, but that's not the same thing -- we need an argument that makes his non-existence logically contradictory).

Since the ontological argument is highly contentious, and unpersuasive to many theists, the objection is likely to stand.

3. Relativised Omnipotence

The conclusion from the above (and from part two) is roughly the following: unless one is willing to embrace some pretty weird doctrines about God (that he could perform some actions that would make him lose divine properties) or the ontological argument, God cannot do everything that it is logically possible to do.

This provides the impetus for a third definition of omnipotence:

- Def. 3 "X is omnipotent" = "X can do everything that it is logically possible for a being with X's defining or necessary properties to do."

This is a relativised form of omnipotence. Applied to God it would read something like "God can do everything that it is possible for an all-knowing, perfectly good and perfectly free being to do."

I actually covered a similar approach to omniscience when dealing with Jeremy Gwiazda's critique of Richard Swinburne. As we saw there, one of the attractions of the relativised definition is that it covers certain problems arising from the concept of free will.

First, if God is himself perfectly free, then he cannot have control over (or knowledge of) his future free actions. Second, one of the most popular responses to the problem of evil is to claim that God has given us the capacity free will and does not have the power to prevent us from exercising that capacity.

You might wonder why it would not be possible for God to prevent us from performing free acts. The answer Everitt gives is that one of God's necessary properties is his non-equivalence with his creation. So because God is not A, he cannot perform A's free actions.

We can charitably allow this kind of sophistry, because there is another problem with this definition. You'll have to wait for the final part to this series for that.

Tuesday, August 10, 2010

Oppy on Disagreement (Part 3)

This post is part of a series on Graham Oppy's article "Disagreement". The article provides an overview of the epistemology of disagreement and considers its application to the philosophy of religion.

Part one covered the basic concepts and questions behind the epistemology of disagreement. The key question is: "What is the rational response to disagreement between doxastic peers?" Part two answered that question by considering several example cases.

As we saw in part two, once we move away from clear-cut hypothetical questions and towards more serious real life disagreements, the answer to the key question becomes elusive. In this part we consider a range of strategies -- identified in the literature -- for coping with real-life disagreements. We then see how these might apply to religious disagreements.

1. Coping with real disagreements

Oppy thinks that the following strategies for coping with real cases of disagreement have been identified in the literature on the epistemology of disagreement (some of these aren't "strategies", more like "observations" that lead to strategies):

- Hard Line: According to this strategy, there are no cases of reasonable disagreement between peers. All actual cases of disagreement are traceable to cognitive or evidential differences between the parties to the disagreement. Thus, it might be reasonable to stick with the beliefs that you have.

- Insight: According to this strategy, it is reasonable to stick with your beliefs if you have reason to think that you have a special insight into the subject matter of disagreement. The problem here is that insight is easy to claim and so appeal to it can seem like an irrational prejudice.

- Extreme philosophical scepticism: According to this strategy, the fact of reasonable disagreement is itself a reason to withhold judgment on all potentially controversial topics. This may be one of the motivations for Pyrrhonian scepticism.

- Moderate philosophical scepticism: Same as the above except the withholding of judgment is limited to cases of actual disagreement.

- Merely Verbal Disagreement: We might be inclined to live with certain disagreements when they are "merely verbal". In other words, when they are matters of linguistic or conceptual bookkeeping as opposed to substantive disputes over what is or is not the case.

- Inscrutability of Reasons: Often, the evidence and reasons on which we base our knowledge claims is inscrutable. This inscrutability might pull us in opposite directions. On the one hand, it might encourage us to be cautious about adjusting our beliefs in the face of disagreement. On the other hand, it might encourage us to be more open-minded.

- Different Starting Points: Given that, in real life, we often arrive at our knowledge claims from different epistemic starting points (prior probabilities, worldviews, presuppositions etc.), we might think caution is preferable when confronted with disagreement. But, then again, maybe the different starting points should incline us toward open-mindedness.

- Insufficient Agreement: It could be that a single instance of disagreement is actually reflective of a much broader range of disagreement. This would go back to the inscrutability of reasons and the different starting points.

- Alethic Impurity: Beliefs and desires often become entangled in our knowledge claims. And given that desires are not thought to have truth values, this might force us to abandon cognitivism about certain disagreements. And this, in turn, might support a non-conciliationist attitude toward disagreement. The problem with this observation is that some disagreements clearly refer to cognitivist areas of inquiry.

As can be seen, there is no single correct response or strategy to take toward actual cases of disagreement. The unsurprising irony is that the epistemology of disagreement has managed to give rise to a whole new set of disagreements.

Oppy considers what this means for cases of religious disagreement.

2. Religious Disagreement

Oppy begins by pointing out that some of the "strategies" outlined above could not apply to religious disagreement. First off, the disagreement is clearly not just a question of linguistic or conceptual bookkeeping. Second, it contains some obviously cognitive components (e.g. "God exists" or "Jesus was resurrected from the dead").*

That said, most of the strategies do apply:

- There are usually different epistemic starting points. For example, some religious believers appeal to the internal witness of the Holy Spirit as constituting their starting point. This can also be viewed as a unique type of "insight". This would be completely alien to a non-believer.

- There is often inscrutability of the reasons for belief or disbelief. Few could identify all the grounds on which they believe/disbelieve in certain religious doctrines.

- Particular instances of disagreement are usually indicative of a much broader territory of disagreement.

- Finally, it is interesting to note that people are usually aware of the disagreement before they adopt their own beliefs. Let's face it, unless we live exceptionally sheltered lives we know that one's stance toward religion is going to be a source of disagreement.

That last observation is particularly suggestive. Of what? Of the fact that mere disagreement is not particularly significant when it comes to assessing the merits of the disputed beliefs. All areas of philosophy are highly contentious and contain many disagreements, this is not surprising.

So for an epistemologist to make the second-order observation that there are cases of peer-disagreement in philosophy tells us nothing that the first-order dispute over reasons-for-belief did not. In other words -- and I take this to be Oppy's key point -- disagreement must be dealt with in the ordinary way: I'll state reasons, provide arguments and pinpoint evidence, and you'll do the same.

This is quite an interesting conclusion.

Oppy on Disagreement (Part 2)

This post is part of a brief series on Graham Oppy's article "Disagreement". The article provides an overview of the epistemology of disagreement and considers its application to cases of religious disagreement.

In part one, I introduced the basic concepts and motivating questions behind the epistemology of disagreement. As we saw, the key question is "What is the rational response to cases of disagreement between doxastic peers?". A doxastic peer is someone who has the same cognitive capabilities, and access to the same information, as you do.

In this part, we consider some examples of disagreement. The examples provide some instruction as to how to answer the key question. However, one of Oppy's key points is that while clear cut answers might be possible in uncomplicated hypothetical examples, once we get closer to real-life cases of disagreement things become much less clear-cut.

1. Cases in which you should adjust your beliefs

We begin with four cases of disagreement in which it would seem rational to change your original belief. They are:

- Restaurant: A group of diners agree to split the bill after a meal in a restaurant. Two of them add-up the items on the bill in order to determine what each individual's contribution should be. The first says the contribution is $63; the second says it is $61. Both are confident that they added-up the figures correctly and both have been shown, in the past, to be equally good at this kind of arithmetic.

- Wrist Watch: Twin brothers are given identical watches for their birthdays. Before going to sleep they synchronise the time on their watches. When they wake up, the first twin reports the time as being 6.45; the second twin reports the time as being 6.51. There is no reason to suspect that either is lying or cognitively disabled in any way.

- Horse Race: A group of punters are watching a horse race. They have each backed different horses. The finish to the race is very tight, with several horses appearing to cross the line at roughly the same time. Nonetheless, one of the punters jumps up, elated that his horse has won. Several other punters do the same thing, even though they backed different horses.

- Perfect Pitch: Two expert musicians, with equal training and experience, are listening to an operatic performance. Their enjoyment of the performance is ruined when they disagree about whether a singer has hit a C or a C-sharp.

Why would it be reasonable to alter the degree of confidence you have in your belief in these types of cases? What do these cases have in common?

Well, they involve people with equal experience and epistemic access to the domain in which the disagreement takes place and, further, that domain is the kind of domain in which even experts may occasionally get things wrong. So it would be strange to assume that one's original judgment must be correct.

2. Cases in which you should not adjust your beliefs

We can contrast the examples just given with the following cases. In these cases, adjustments seems less rational:

- Elementary Math: Two departmental colleagues, who have known and worked with each other for over a decade, are trying to work how many people will be attending an upcoming conference. The first one, reasoning out loud, says that two people will be attending on Wednesday and two on Thursday. That means four in total. The second colleague disagrees, saying "But 2+2 does not equal 4".

- Perception: Three roommates, who have been living together for several years, are silently enjoying lunch. The first roommate asks the second to pass the salt to the third, who is gesturing at the other end of the table. The second roommate refuses on the grounds that the third roommate is not present.

- Directions: Two neighbours, who have lived in the same area for several years, meet each other while out walking around the neighbourhood. The first tells the second that he is going to his favourite restaurant. The second -- who is also a fan of the restaurant -- tells him that he is heading in the wrong direction. The first disagrees.

- Bird: You and your best friend are in the university library. You are both staring out the window. You notice a bird flying past. You turn to your friend and ask "What type of bird was that?". Your friend claims there was no bird.

Why would adjustment be irrational in these cases? What do they have in common?

Well, they would seem to involve cognitively basic judgments. That is, judgments about immediate perceptual experience, personal memory or elementary math and logic. These are not the kinds of judgments we expect to be mistaken about.

3. More Problematic Cases

Those cases were relatively straightforward. The following cases are more tricky because they involve complex judgments about complex topics. It is not clear what should be done in these cases.

We might worry about whether the experts in these examples are really peers since it would be difficult to determine if they have the exact same experience, ability and evidence. Still, they are close to serious, real-life cases of disagreement. How we respond to these types of disagreement can be significant.

- Meteorologists: Two highly experienced and respected meteorologists are asked to predict the likelihood of rain tomorrow. They both avail of the most up-to-date techniques for computer modelling of the weather and they feed the same data into their models. After doing so, the first meteorologist says there is a .55 probability of rain tomorrow, the second says there is a .35 probability of rain.

- Detectives: Two experienced and successful detectives are both investigating the same case. The evidence is very complicated. Some of it points toward one suspect; some of points toward another suspect. After analysing all the evidence, they both decide upon a different culprit.

- Doctors: Two impeccably well-educted doctors, with oodles of clinical experience are called-in to consult on a particularly difficult case. They both run the same tests and consider the same case history. After doing so, the first physician thinks that the patient has chronic fatigue syndrome. The second thinks the patient has lupus.

We might worry about whether the experts in these examples are really peers since it would be difficult to determine if they have the exact same experience, ability and evidence. Still, they are close to serious, real-life cases of disagreement. How we respond to these types of disagreement can be significant.

As can be seen in the following case:

- Two Expert Judges: Suppose there are two expert judges who agree in 90% of cases and disagree in 10%. Suppose further that they are each correct in 95% of cases. So of the 10% of cases involving disagreement, each judge will be right in 5% of the cases. It just happens that there is no way of knowing which 5%.

If you are following their judgments, what should you do when they disagree? That depends on whether you want to get at the truth or avoid error. If you want to get at the truth you would be better off following one of the judges (since you will then be right 95% of the time). But if you want to avoid error, you should suspend judgment.

In the criminal law, the goal is usually thought to be to avoid error. The famous English jurist William Blackstone once observed (I'm paraphrasing) "'tis better for 10 guilty men to go free than for one innocent man to be punished." The problem is that this could be crippling. For imagine if we had several experts, who are usually right, but disagree across a broad spectrum of cases. In that event, we would have to suspend judgment in nearly every case.

In the next part, we will move on to consider religious disagreement.

In the next part, we will move on to consider religious disagreement.

Oppy on Disagreement (Part 1)

For some reason, the epistemology of disagreement is a hot topic in the world of philosophy at the minute. It looks at a number of scenarios in which epistemic (or doxastic) peers disagree and wonders what is the rational response to such disagreements. I suspect that this interests philosophers since they tend to disagree so much, and their disagreements seem to be perpetual.

Of course, one area which generates a lot of disagreement is the philosophy of religion. There, people of seemingly equal philosophical acumen and care can have profound disagreements. So it is natural that the current fad for the epistemology of disagreement should wander into this fevered pit of philosophical debate.

While reading exapologist's blog recently, I came across a paper by Graham Oppy on the potential significance of the epistemology of disagreement for the philosophy of religion. Unsurprisingly given his previous work, Oppy is not sure that any special insight into religious disagreement can actually be gained with this fad, at least in its present form.

In the process of dampening enthusiasm, Oppy nonetheless provides an excellent overview of the epistemology of disagreement. So by going through his article we can both learn something about this burgeoning field of philosophical inquiry as well as its potential application to areas of serious disagreement.

In this introductory post, I will introduce the key concepts and questions from the epistemology of disagreement (as identified by Oppy).

1. Key Concepts

I am afraid that this will be nothing more exciting than a list of concepts. Here we go:

- Disagreement: A disagreement arises whenever two or more people have different attitudes toward a proposition. For example, Ann and Bob might have different attitudes toward the proposition "Barack Obama is the greatest U.S. president ever." Ann thinks it is true; Bob thinks that nothing could be more ridiculous.

- Reasonable Disagreement: A disagreement is reasonable if it does not seem to arise from any cognitive or evidential flaw or error. In other words, nothing seems to have gone wrong in the process that led to Ann and Bob forming their different attitudes. This may result in the parties agreeing to disagree.

- Cognitive Comparators: People are cognitive peers if they have equal cognitive ability, i.e. they are equally good at perceiving, remembering, inferring and so on. It is also possible for people to be cognitive superiors or inferiors. When talking about cognitive superiority/parity we may only be talking about specific domains of knowledge.

- Evidential Comparators: People are evidential peers if they have access to the same evidence, i.e. they are equally well informed about a given topic. Again, it is possible for them to be superiors or inferiors as well.

- Doxastic Comparators: This is simply a combination of the cognitive and evidential dimensions. So, for example, people are doxastic peers if they have equal cognitive ability and are equally well-informed. One may wonder whether it is actually possible for genuine doxastic peers to exist.

- Belief: A "belief" can be understood in two different ways. Either (i) an all-or-nothing attitude toward a proposition (true/false); or (ii) a graded attitude toward a proposition (e.g. "55% true"). Oppy prefers the graded conception.

- Rationality: One of the main goals of the epistemology of disagreement is to discovery the rational response to disagreement between doxastic peers. "Rationality" here is understood as a normative standard of belief revision. Although no one's quite sure what those norms are, Oppy will assume they can be determined.

2. Key Questions

As mentioned above, one of the main goals of epistemology of disagreement is to answer the question "What should doxastic peers do when they learn that they disagree about some proposition P?".

Two extreme positions have been identified in the literature. The first is the conciliationist or conformist position. According to this position, when two people learn that they disagree about a proposition, and they have established their peer-status, they should split the difference between their respective attitudes. In other words, they should give proportional weight to both their own view and the view of their peer.

The second position is the steadfast or non-conformist position. No prizes will be awarded for guessing that this means, in the event of disagreement between doxastic peers, each should stick with the beliefs they originally had.

In the next part of this series we will consider some "toy" cases in which these extreme positions might be appropriate. However, we may wonder about their general applicability. Oppy suggests that the Bayesian position -- "always conditionalise your belief on the evidence" -- is a possible answer to the problem of disagreement and that it is quite distinct from the two extreme positions outlined above.

Apparently, he is preparing an article which will flesh out this Bayesian position in more detail. So we will have to wait and see what it really entails.

Okay, that's enough for now. The next part looks at different cases of disagreement.

Two extreme positions have been identified in the literature. The first is the conciliationist or conformist position. According to this position, when two people learn that they disagree about a proposition, and they have established their peer-status, they should split the difference between their respective attitudes. In other words, they should give proportional weight to both their own view and the view of their peer.

The second position is the steadfast or non-conformist position. No prizes will be awarded for guessing that this means, in the event of disagreement between doxastic peers, each should stick with the beliefs they originally had.

In the next part of this series we will consider some "toy" cases in which these extreme positions might be appropriate. However, we may wonder about their general applicability. Oppy suggests that the Bayesian position -- "always conditionalise your belief on the evidence" -- is a possible answer to the problem of disagreement and that it is quite distinct from the two extreme positions outlined above.

Apparently, he is preparing an article which will flesh out this Bayesian position in more detail. So we will have to wait and see what it really entails.

Okay, that's enough for now. The next part looks at different cases of disagreement.

Saturday, August 7, 2010

Episode 4 - Theology and Falsification

Episode 4 of the podcast is available for download here. In this episode, a classic contribution to 20th century philosophy of religion is analysed. The contribution in question is the symposium in which Antony Flew's short paper "Theology and Falsification" was presented and discussed.

You can subscribe to the podcast on iTunes.

It's been awhile since I read Flew's paper and re-reading it for this podcast made me realise how many important issues it, and the symposium accompanying it, raise. This is all the more impressive given how short and relatively devoid of formal argumentation the original papers are. Admittedly, I may be getting more out of it thanks to my reading in the interim. I will also confess that I have adopted a favourable interpretation of Flew's work.

The original paper, along with the responses of R.M. Hare and Basil Mitchell can be found here.

Horsburgh's critique of Hare's notion of bliks is available here.

Finally, I prepared some notes to accompany the show.

Flew's Argument

|

| click to see a larger version |

Hare's Argument

|

| click to see a larger version |

Mitchell's Argument

|

| click to see a larger version |

Flew's Responses

|

| click to see a larger version |

Horsburgh on Hare

|

| click to see a larger version |

Edit: Almost forgot to include this. It's William Lane Craig talking about the role that evidence and argument play in his religious faith. A nice illustration of what Mitchell's argument can lead to:

Friday, August 6, 2010

Surveillance and Moral Character: Kantian and Hobbesian Citizens

Some variation from the norm today.

I occasionally read a magazine called Philosophy Now. It's actually quite good and I would recommend it to anyone as a repository of short, sometimes incisive, philosophy articles. In the most recent issue, one article in particular caught my eye. It was entitled "Does Surveillance make us Morally Better?" and it was by Emrys Westacott.

Why did this catch my eye? Well, I'm interested in how the design of social systems affects our capacity to be responsible people. (In this instance, I intend "responsible" to describe a positive character trait as opposed to a necessary precondition for punishment.) And the use of surveillance equipment is one of the things that could affect this capacity.

I also think that the paper deals with some concerns about moral character that are philosophically and intuitively appealing. It is an issue on which I am conflicted.

To begin with I'll introduce the basic debate and Westacott's take on it.

1. The Kantian and Hobbesian Citizen

Norms are the intangible infrastructure of society. A society is a network of interacting agents who develop certain standards of behaviour that they expect both themselves and others to adhere to. These standards are what we call norms.

Generally, we want people to comply with the norms, and there are two ways of getting them to do so. The first -- what we might call the Hobbesian way -- is to threaten them with violence or other punitive repercussions. The second -- what we might call the Kantian way -- is to get them to follow the norms because this is the right thing to do. Or, in a more Kantian guise, because this is constitutive of morally good practical rationality.

These two different methods of norm-compliance give rise to two different types of citizen. The Hobbesian citizen is the one who acts largely for prudential, self-regarding reasons; the Kantian citizen is the one who acts for moral or self-actualising reasons.

There are reasons for encouraging both methods of norm-compliance. On the one hand, the Hobbesian method might be more practical and might reduce the level of norm-defiance. On the other hand, the Kantian method might be thought to breed a morally superior and more self-fulfilled citizenry.

2. The Six Stages of Traffic Surveillance

Surveillance can obviously form an important part of a norm-compliance programme. In a previous post, I considered the role that divine surveillance might play in compliance. Westacott opts for a more mundane illustration involving six stages of traffic surveillance.

As we can see, surveillance equipment plays a vital role in the evolution from the state of lawlessness to the state of near-perfect compliance.

I occasionally read a magazine called Philosophy Now. It's actually quite good and I would recommend it to anyone as a repository of short, sometimes incisive, philosophy articles. In the most recent issue, one article in particular caught my eye. It was entitled "Does Surveillance make us Morally Better?" and it was by Emrys Westacott.

Why did this catch my eye? Well, I'm interested in how the design of social systems affects our capacity to be responsible people. (In this instance, I intend "responsible" to describe a positive character trait as opposed to a necessary precondition for punishment.) And the use of surveillance equipment is one of the things that could affect this capacity.

I also think that the paper deals with some concerns about moral character that are philosophically and intuitively appealing. It is an issue on which I am conflicted.

To begin with I'll introduce the basic debate and Westacott's take on it.

1. The Kantian and Hobbesian Citizen

Norms are the intangible infrastructure of society. A society is a network of interacting agents who develop certain standards of behaviour that they expect both themselves and others to adhere to. These standards are what we call norms.

Generally, we want people to comply with the norms, and there are two ways of getting them to do so. The first -- what we might call the Hobbesian way -- is to threaten them with violence or other punitive repercussions. The second -- what we might call the Kantian way -- is to get them to follow the norms because this is the right thing to do. Or, in a more Kantian guise, because this is constitutive of morally good practical rationality.

These two different methods of norm-compliance give rise to two different types of citizen. The Hobbesian citizen is the one who acts largely for prudential, self-regarding reasons; the Kantian citizen is the one who acts for moral or self-actualising reasons.

There are reasons for encouraging both methods of norm-compliance. On the one hand, the Hobbesian method might be more practical and might reduce the level of norm-defiance. On the other hand, the Kantian method might be thought to breed a morally superior and more self-fulfilled citizenry.

2. The Six Stages of Traffic Surveillance

Surveillance can obviously form an important part of a norm-compliance programme. In a previous post, I considered the role that divine surveillance might play in compliance. Westacott opts for a more mundane illustration involving six stages of traffic surveillance.

- Stage One: The state of nature -- it's every driver for himself. There are no rules. Life is nasty, brutish and depressingly short.

- Stage Two: The government introduces some rules dictating which side of the road you should drive on, as well as the maximum speed at which you should drive. The rules are widely ignored due to poor enforcement.

- Stage Three: Highway patrols are started and this limits some of the rule-breaking. But drivers are clever and find ways to avoid the police.

- Stage Four: More police, with radar technology, are put out on the roads. This increases the level of enforcement and speeding becomes imprudent. Still, some drivers learn where the "speed traps" are and use technology that disrupts the police radar.

- Stage Five: Police use speed cameras and satellite monitors. Detection and prosecution becomes automated. Speeding becomes a high cost endeavour.

- Stage Six: All cars are equipped with devices that can detect the speed limit for the road on which they are driving. The car's computer then puts an automatic cap on the speed at which the driver can travel. Near-perfect norm-compliance is achieved.

As we can see, surveillance equipment plays a vital role in the evolution from the state of lawlessness to the state of near-perfect compliance.

But in doing so, a Hobbesian method is prioritised over a Kantian method. People are encouraged to obey the law out of a fear of being caught, not out of a love for "doing the right thing". This may seem to diminish or degrade the rationality and humanity of the members of a society. And if surveillance becomes a pervasive and ever present phenomenon, it could seriously hinder our moral development.

Those, at least, are the concerns of the Kantian.

Those, at least, are the concerns of the Kantian.

3. Why the Kantian Might be Wrong

Westacott identifies four reasons for dismissing the Kantian concerns. First, we might be inclined to think that the panopticon-society is an academic fiction: it'll never happen and the opportunities for moral development will never be completely eroded.

Second, we might think that the Kantian concern is based on an outmoded conception of humanity and morality. One that is grounded in Christian ideas of sinfulness and guilt.

Third, the saintly Kantian ideal might be pragmatically deficient. What matters is what people actually do, not how they think about what they do. This would seem to coincide somewhat with the liberal ideal of total freedom of thought and conscience tempered only by the harm principle.

Fourth, it might be that Kantians should embrace increased surveillance. For it is through increased surveillance that the Kantian fetish with duty is made to coincide with self-interest. So surveillance can foster the good habits that the Kantian demands.

4. The Continued Resonance of the Kantian Ideal

This last reason might seem to reconcile the Kantian and Hobbesian views. But Westacott is unconvinced. He asks us to imagine some scenarios. He thinks these scenarios show that the Kantian opposition to surveillance still resonates.

The first scenario involves two different universities. The first, called Scrutiny College, equips its examination rooms with the latest hi-tech surveillance equipment. It prides itself on catching and punishing cheats. The second, called Probity College, operates on a classic honour system. Students sign a pledge not to cheat and there is subsequently no surveillance or monitoring of their activities.

Two further scenarios are presented by Westacott. They are replications of the first but in different arenas. One deals with two different work environments. The other deals with two different parenting styles.

Westacott seems to think it obvious that we would prefer to attend Probity college, to work somewhere without constant surveillance, and to raise children who didn't need intrusive monitoring of their activities. Thus, we obviously still have a hankering for the Kantian ideal.

I'm not entirely sure that these thought experiments do the work Westacott wishes them to do. I'm particularly leery about the university one. I would personally prefer to attend and work at a university that does not tolerate cheating. Maybe this is because (a) I have spent too much time at university and (b) I have spent a some of that time studying game theory and this has taught me that a degree from a university with low standards sends a poor signal on the job market.

5. Different Classes of Relationship

In fairness, Westacott suggests that our attitude toward surveillance can vary depending on the type of relationship that exists between the surveyor and surveyed. He mentions four such relationships: parent-child, student-teacher, employer-employee, and state-citizen.

He thinks that surveillance is less problematic in the state-citizen and employer-employee context. However, he thinks it is problematic in the parent-child and student-teacher context. Why? Because it is within those relationships that the process of moral development really takes place.

For my part, I can understand the lure of the Kantian ideal. I like the idea of living life free from intrusion and surveillance, I like the ideal of personal responsibility, and I worry about excessive regulation and surveillance. Still, my pragmatic streak makes me lean toward the Hobbesian method when thinking -- as I do -- about how the law should be reformed and how social systems should be designed.

Thus, I would prefer if the reconciliation could be effected.

Second, we might think that the Kantian concern is based on an outmoded conception of humanity and morality. One that is grounded in Christian ideas of sinfulness and guilt.

Third, the saintly Kantian ideal might be pragmatically deficient. What matters is what people actually do, not how they think about what they do. This would seem to coincide somewhat with the liberal ideal of total freedom of thought and conscience tempered only by the harm principle.

Fourth, it might be that Kantians should embrace increased surveillance. For it is through increased surveillance that the Kantian fetish with duty is made to coincide with self-interest. So surveillance can foster the good habits that the Kantian demands.

4. The Continued Resonance of the Kantian Ideal

This last reason might seem to reconcile the Kantian and Hobbesian views. But Westacott is unconvinced. He asks us to imagine some scenarios. He thinks these scenarios show that the Kantian opposition to surveillance still resonates.

The first scenario involves two different universities. The first, called Scrutiny College, equips its examination rooms with the latest hi-tech surveillance equipment. It prides itself on catching and punishing cheats. The second, called Probity College, operates on a classic honour system. Students sign a pledge not to cheat and there is subsequently no surveillance or monitoring of their activities.

Two further scenarios are presented by Westacott. They are replications of the first but in different arenas. One deals with two different work environments. The other deals with two different parenting styles.

Westacott seems to think it obvious that we would prefer to attend Probity college, to work somewhere without constant surveillance, and to raise children who didn't need intrusive monitoring of their activities. Thus, we obviously still have a hankering for the Kantian ideal.

I'm not entirely sure that these thought experiments do the work Westacott wishes them to do. I'm particularly leery about the university one. I would personally prefer to attend and work at a university that does not tolerate cheating. Maybe this is because (a) I have spent too much time at university and (b) I have spent a some of that time studying game theory and this has taught me that a degree from a university with low standards sends a poor signal on the job market.

5. Different Classes of Relationship

In fairness, Westacott suggests that our attitude toward surveillance can vary depending on the type of relationship that exists between the surveyor and surveyed. He mentions four such relationships: parent-child, student-teacher, employer-employee, and state-citizen.

He thinks that surveillance is less problematic in the state-citizen and employer-employee context. However, he thinks it is problematic in the parent-child and student-teacher context. Why? Because it is within those relationships that the process of moral development really takes place.

For my part, I can understand the lure of the Kantian ideal. I like the idea of living life free from intrusion and surveillance, I like the ideal of personal responsibility, and I worry about excessive regulation and surveillance. Still, my pragmatic streak makes me lean toward the Hobbesian method when thinking -- as I do -- about how the law should be reformed and how social systems should be designed.

Thus, I would prefer if the reconciliation could be effected.

Thursday, August 5, 2010

Omnipotence (Part 2)

This post is part of my series on Nicholas Everitt's book The Non-Existence of God. For an index, see here.

I am currently looking at Chapter 13 of the book. This chapter considers arguments against the possibility of an omnipotent god. If these arguments are successful, they would undermine the classical conception of God.

As noted in part 1, the arguments against omnipotence depend on unearthing the contradictions that might be inherent in the notion of an all-powerful being. This, in turn, depends on how we define omnipotence. Everitt considers five possible definitions. The second of these is probably the most common:

Def 2: "X is omnipotent" = "X can do everything which it is logically possible to do"As we saw at the end of part 1, there are several problems with this definition. For example, it is possible for human beings to commit suicide, but it is not possible for God to do the same. Likewise, there are certain actions that humans can perform that require a physical body which God, being immaterial, lacks. Furthermore, it is possible for humans, because of their moral imperfection, to perform morally evil acts, but it is not clear that God, because of his moral perfection, could do the same. Finally, there is the classic "could God make a stone so heavy that not even he could lift?"-objection.

We continue now by looking at the ways in which theists can avoid the last two of these problems.

1. The Superheavy Stone

The problem with the superheavy stone is that if God can make it, then he won't be able to lift it and so is not all-powerful, and if he cannot make it then there is something he cannot do. So either answer to the question "could God make a stone...?" seems to undermine the concept of omnipotence. Everitt notes that theists have tried to provide defences of both answers.

Some argue that God could make the stone and that so long as he never actually makes it his omnipotence is preserved. This is a strange solution to the problem. It seems to concede that God could be omnipotent at one moment (prior to making the superheavy stone) but not at another (after making the stone). But wouldn't this be tantamount to saying that God would cease to exist after making a superheavy stone?

This is hardly a theologically reassuring line of thought. However, there is another way to defend the "yes"-answer. This turns on an analysis of what is and is not a logical possibility. The theist can accept that it is logically possible for God to create a superheavy stone. Then, they can turn around and deny that it is logically possible for an omnipotent being to lift an unliftable stone.

Of course, the same reasoning can be turned on its head in order to support a negative answer to the original question. So, for example, the theist could say that the creation of an unliftable stone is not a logically possible task.

Now maybe this is wrong. But it would take a fairly sophisticated analysis of what "logical possibility" really means to defeat it. As a result, Everitt thinks it is best to ignore the superheavy stone objection.

2. Can God Sin?

As mentioned above, it is possible for human beings to sin. But it is not clear that a morally perfect being like God could do the same. Thus, there is something that God cannot do.

The theist can respond to this objection in a manner similar to the first response to the idea of the superheavy stone. In other words, they can say that God could perform a morally evil act, but that provided he never does he never compromises his moral perfection.

Again, this concedes that God could cease to have one of his defining properties. And the deeper problem with this is that it would seriously damage the concept of moral perfection. If all that is needed for moral perfection is the failure to act immorally at certain moments, then we are all morally perfect on occasion.

This would seem to make a mockery of the notion of a morally perfect being. The theist needs a being who cannot do moral wrong, not just one that fails to do a moral wrong. But then this runs foul of the original objection. The only way out of this is to tack on an arbitrary qualification to Definition 2 stating that omnipotence precludes moral wrong.

Everitt thinks that a more promising solution is available to the theist but that it will require a completely new definition of omnipotence. We will consider that definition in due course.

That's where we'll leave it for today. In the next part we will consider theistic solutions to the problem of God's immateriality and immortality.

Tuesday, August 3, 2010

Omnipotence (Part 1)

This post is part of my series on Nicholas Everitt's book The Non-Existence of God. For an index, see here.

It's been awhile since I dipped into Everitt's excellent introduction to the philosophy of religion and it's about time that trend was reversed. In the next few posts I will take a look at Chapter 13 of the book. The chapter deals with the topic of omnipotence.

It has been pointed out to me that some of the more interesting atheological work comes in the shape of positive arguments against the consistency and coherence of the classical understanding of God. Everitt's chapter on omnipotence does just that by critically examining the idea of an all-powerful God.

Let's see what he has to say.

1. Self-Contradiction

The type of argument that Everitt considers in chapter 13 is dependent on the notion of self-contradiction. In other words, on the idea that some concepts are self-contradictory and hence impossible.

What kind of self-contradiction would be involved in the concept of God? Let's take two examples. The first is that of a circular square. In this case there is a straightforward and obvious contradiction inherent in the concept: something cannot be both circular and square.

Sometimes, things are less obvious. A good example of this is the concept of the highest prime number. As we all know, there is no such thing as the highest prime number. Indeed, one of the first mathematical proofs I ever learned was the proof of the infinitude of primes.

But notice that the contradiction is not immediate or obvious. We have to do some formal analytical and logical work before it reveals itself. If the concept of God is self-contradictory, it is likely to be contradictory in this second, less immediate manner.

2. Divine Power

Before we look for contradictions, let's try to understand how God would exert his power. We will do this by way of analogy to our own powers.

Whenever we want to exert power and influence, we do so by chaining together long sequences of bodily movements. For example, if you want to change TV channels you will have to pick up the remote control and press the appropriate buttons. And if you want to overthrow the government, you must find a group of like-minded revolutionaries and then plot and plan a revolution. That takes a lot of effort.

It is assumed by most theists that God's power is not exerted in the same way. If God wants something to be the case, he doesn't have to take all the intermediary steps mentioned above. He can directly will whatever he wants.

Does this make his power unintelligible? Not at all. For we can directly will things as well. Take the example of raising your hand. You can do this directly without willing the intermediary steps involving the firing of neurons in the motor cortex. Now imagine this power could be extended over everything you wish to do and you begin to get close to the idea of God.

3. Defining Omnipotence

In searching for contradictions in the concept of omnipotence, we will follow a simple method. We will begin with a definition of the concept and see if that definition entails any absurdities. All told, there will be five separate definitions. In the remainder of this post we will deal with the first two.

The first definition is the most straightforward:

Def 1: "X is all powerful" = "X can do everything"This immediately runs into the brick wall of logical impossibility. In other words, it forces us to ask whether God can do things that are logically impossible, such as make it the case that "1+1=3" or that triangles actually have four sides. If he could, we would landed in a bizarre and arbitrary Alice-in-Wonderland-like universe.