Here are the remaining argumentation schemes following on from the previous post.

More to chew over here.

8. Argument from Sign

9. Argument from Commitment

10. Argument from Inconsistent Commitment

11. Direct Ad Hominem Argument

12. Circumstantial Ad Hominem

13. Argument from Verbal Classification

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Argumentation Schemes (Part 1)

I don't know if anybody is interested in this kind of thing, but in case they are the following is based on a set of handouts I once prepared on argumentation schemes. It is based on work by the argumentation theorist Douglas Walton (taken specifically from this book). He has literally written the book on every informal fallacy out there, worth checking out.

The argumentation schemes here are what Walton calls "common presumptive arguments". A presumptive argument is, according to Walton, not based on deductive nor inductive principles. Instead, it is based on defeasible presumptions. They are far more common in argument than we might care to think, so familiarity with them is essential.

Each image provides the abstract form of the argument, an example and a set of critical questions.

1. Argument from the Position to Know

2. Appeal to Expert Opinion

3. Appeal to Popular Opinion

4. Argument from Analogy

5. Argument from Correlation to Cause

6. Argument from Positive/Negative Consequences

7. The Slippery Slope Argument

The argumentation schemes here are what Walton calls "common presumptive arguments". A presumptive argument is, according to Walton, not based on deductive nor inductive principles. Instead, it is based on defeasible presumptions. They are far more common in argument than we might care to think, so familiarity with them is essential.

Each image provides the abstract form of the argument, an example and a set of critical questions.

1. Argument from the Position to Know

2. Appeal to Expert Opinion

3. Appeal to Popular Opinion

4. Argument from Analogy

5. Argument from Correlation to Cause

6. Argument from Positive/Negative Consequences

7. The Slippery Slope Argument

Monday, March 29, 2010

Hume on Morality (Part 1): Historical Background

This post is part of my series on Hume's moral philosophy. The series works from the article "The Foundations of Morality in Hume's Treatise" by David Fate Norton in the Cambridge Companion to Hume. For an index, see here.

As noted in the index, this series looks at Hume's answers to the questions of moral ontology and moral epistemology. Hume's answers fit within the context of certain trends in late 17th, early 18th century philosophy. In this opening post, we will examine these trends.

This entails a quick summary of the moral theories of four dead, white European males: Samuel Clarke, Anthony Ashley Cooper (3rd Earl of Shaftesbury), Bernard Mandeville, and Francis Hutcheson.

Those of you who are averse to intellectual history should still find this pretty interesting (particularly since it shows how little has changed in this area).

1. Samuel Clarke

Clarke stakes out a fairly standard theistic/natural law position on the foundations of morality. To Clarke, every contingent ontological entity (such as a human beings) owes its existence to a necessary, unchanging, infinite, and personal being. This being is perfectly good and just.

All created beings have essential and eternal differences in their properties and attributes. These differences make some actions morally right and some morally wrong. To put it another way, there is a direct correspondence between moral goodness and our essential nature.

We come to know about these moral distinctions through the operations of our reason. In much the same way that we come to appreciate scientific and mathematical principles. The only difference is that we can voluntarily accept or reject moral distinctions. We cannot do the same for mathematical or scientific principles. For example, it would be impossible to deny the truth of "1+1=2".

That said, Clarke argued that although we can reject moral truths, it would be absurd to do so: we would know that we were doing something irrational.

2. Anthony Ashley Cooper (3rd Earl of Shaftesbury)

Shaftesbury's moral theory begins in a similar vein to that of Clarke. He makes an appeal to something called the "frame of nature", which is the systematic interconnection of every living thing. Each living thing has an appropriate locus within this frame. They do good by sticking to this locus; they do bad by trying to upset the applecart.

A more interesting aspect of Shaftesbury's work was his analysis of virtue and vice. The virtuous act, he argued, was more than simply a positive contribution to the welfare of others: it was an act that was the product of a rationally determined motivation to do good.

For example, suppose a man threw some bread out of the window of his car because he wished to despoil some aesthetically pleasing landscape. Unbeknownst to him, the bread is taken and eaten by a homeless and destitute beggar. Contrast this with a man who willing gives a loaf of bread to the beggar in the hope that it will be of some comfort to him. Although both acts have the same consequence, to which would the term "virtuous" more appropriately attach? I suspect we all know the answer to that.

Shaftesbury was deeply critical of the influential moral and political theorists Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. He felt that both men tried, in their theories, to eliminate true virtue. Hobbes did this by reducing all supposedly virtuous acts to self-interested acts that were performed for mutual advantage. Locke was more subtle but committing the same mistake as Hobbes by concluding that virtue was a product of cultural convention.

3. Bernard Mandeville

Alas, I could not find a picture of Bernard Mandeville but the above is a facsimile of the title page of his most famous work The Fable of the Bees. Mandeville's key argument was that morality was a sham. An artificial system of thought, foisted upon us in order to prevent us from following our true self-interests.

Mandeville agrees with Shaftesbury: the virtuous act is the product of a rational motivation to do good. He simply thinks that a close examination of human action reveals that such motivations do not exist. Indeed, on closer inspection we find that all actions stem from passions (anger, pride, fear, happiness, pity etc.); and that all passions are self-interested. It just so happens that some passions benefit the public.

But if Mandeville's analysis is correct, a question arises: whence all this talk of virtue? Mandeville answers with an inventors story (we might put evolutionary just-so stories in a similar class these days). Simply described, the governor's of society worked out that there were not enough tangible material resources available to reward all people for their good acts or to punish people for bad acts. So they substituted intangible rewards and punishments, i.e. moral flattery and moral condemnation.

These intangible rewards and punishments are not in our interest, but we have been duped into thinking that they are.

4. Francis Hutcheson

The final member of the pre-Hume quartet, Francis Hutcheson, tried to defend Shaftesbury from Mandeville's attack. He argued, contra Mandeville, that some human activities clearly testify to the reality of virtue. For example:

As noted in the index, this series looks at Hume's answers to the questions of moral ontology and moral epistemology. Hume's answers fit within the context of certain trends in late 17th, early 18th century philosophy. In this opening post, we will examine these trends.

This entails a quick summary of the moral theories of four dead, white European males: Samuel Clarke, Anthony Ashley Cooper (3rd Earl of Shaftesbury), Bernard Mandeville, and Francis Hutcheson.

Those of you who are averse to intellectual history should still find this pretty interesting (particularly since it shows how little has changed in this area).

1. Samuel Clarke

Clarke stakes out a fairly standard theistic/natural law position on the foundations of morality. To Clarke, every contingent ontological entity (such as a human beings) owes its existence to a necessary, unchanging, infinite, and personal being. This being is perfectly good and just.

All created beings have essential and eternal differences in their properties and attributes. These differences make some actions morally right and some morally wrong. To put it another way, there is a direct correspondence between moral goodness and our essential nature.

We come to know about these moral distinctions through the operations of our reason. In much the same way that we come to appreciate scientific and mathematical principles. The only difference is that we can voluntarily accept or reject moral distinctions. We cannot do the same for mathematical or scientific principles. For example, it would be impossible to deny the truth of "1+1=2".

That said, Clarke argued that although we can reject moral truths, it would be absurd to do so: we would know that we were doing something irrational.

2. Anthony Ashley Cooper (3rd Earl of Shaftesbury)

Shaftesbury's moral theory begins in a similar vein to that of Clarke. He makes an appeal to something called the "frame of nature", which is the systematic interconnection of every living thing. Each living thing has an appropriate locus within this frame. They do good by sticking to this locus; they do bad by trying to upset the applecart.

A more interesting aspect of Shaftesbury's work was his analysis of virtue and vice. The virtuous act, he argued, was more than simply a positive contribution to the welfare of others: it was an act that was the product of a rationally determined motivation to do good.

For example, suppose a man threw some bread out of the window of his car because he wished to despoil some aesthetically pleasing landscape. Unbeknownst to him, the bread is taken and eaten by a homeless and destitute beggar. Contrast this with a man who willing gives a loaf of bread to the beggar in the hope that it will be of some comfort to him. Although both acts have the same consequence, to which would the term "virtuous" more appropriately attach? I suspect we all know the answer to that.

Shaftesbury was deeply critical of the influential moral and political theorists Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. He felt that both men tried, in their theories, to eliminate true virtue. Hobbes did this by reducing all supposedly virtuous acts to self-interested acts that were performed for mutual advantage. Locke was more subtle but committing the same mistake as Hobbes by concluding that virtue was a product of cultural convention.

3. Bernard Mandeville

Alas, I could not find a picture of Bernard Mandeville but the above is a facsimile of the title page of his most famous work The Fable of the Bees. Mandeville's key argument was that morality was a sham. An artificial system of thought, foisted upon us in order to prevent us from following our true self-interests.

Mandeville agrees with Shaftesbury: the virtuous act is the product of a rational motivation to do good. He simply thinks that a close examination of human action reveals that such motivations do not exist. Indeed, on closer inspection we find that all actions stem from passions (anger, pride, fear, happiness, pity etc.); and that all passions are self-interested. It just so happens that some passions benefit the public.

But if Mandeville's analysis is correct, a question arises: whence all this talk of virtue? Mandeville answers with an inventors story (we might put evolutionary just-so stories in a similar class these days). Simply described, the governor's of society worked out that there were not enough tangible material resources available to reward all people for their good acts or to punish people for bad acts. So they substituted intangible rewards and punishments, i.e. moral flattery and moral condemnation.

These intangible rewards and punishments are not in our interest, but we have been duped into thinking that they are.

4. Francis Hutcheson

The final member of the pre-Hume quartet, Francis Hutcheson, tried to defend Shaftesbury from Mandeville's attack. He argued, contra Mandeville, that some human activities clearly testify to the reality of virtue. For example:

- The moral approval and disapproval of people who are dead. (This can't be done in self-interest since these people cannot improve our lot in life).

- The fact that we assess someone's motive irrespective of how their actions may have affected us.

- The fact that although we can bribed to perform a morally vicious action, we cannot be bribed into think such an action is virtuous.

Thinking that reality of virtue is well-established, Hutcheson proceeds to the following question: what feature of human nature needs to be presupposed in order to explain virtue? It is at this point that Hutcheson rubs up against modern theories of evolved moral instincts.

Hutcheson argues that there must be a moral sense with volitional and cognitive components. On the volitional side, the moral sense motivates us to perform our actions with general benevolence and desire for the happiness of others. On the cognitive side, the moral sense allows us to discriminate between the motivations of other people.

It is important to note that Hutcheson did not feel he was reducing virtue and vice to a set of feelings produced by a moral sense. On the contrary, he thought the moral sense was responding to objective, observer-independent moral properties.

Hume, as we shall see in the remainder of this series, begged to differ.

Saturday, March 27, 2010

Hume on Morality (Index)

I've already done one series covering Hume's arguments on religion. One thing that disappointed me when writing up that series was the insufficient attention it paid to Hume's moral philosophy. This series tries to fill the gap.

As with my series on Hume's religious philosophy, I am going to work off an article in the excellent Cambridge Companion to Hume. On this occasion my chosen article is "The Foundations of Morality in Hume's Treatise" by David Fate Norton.

This article covers Hume's contributions to the contemporary (i.e. 18th C) debate on moral ontology and epistemology. In other words, it deals with Hume's attempt to answer the following questions:

- What features of the natural world do our judgements of right and wrong actually reflect? Do they reflect principles that are woven into the fabric of reality or do they merely reflect our own self-interests and prejudices?

- Which of our cognitive faculties (Reason or Emotion) enable us to grasp these moral distinctions?

This index will grow as I work my way through the article.

Index

Maitzen on Morality and Atheism (Index)

Index

1. Maitzen on Morality and Skeptical Theism

2. Maitzen on Ordinary Morality and Atheism

Tuesday, March 23, 2010

Maitzen on Ordinary Morality and Atheism (Part 2)

This post is the second part in my series on Stephen Maitzen's article "Ordinary Morality Implies Atheism". If you haven't read the first part, you really should.

1. The Core Argument

Part 1 presented the outline of Maitzen's argument. The logic of the argument is easy to grasp. It comes in two halves. The first argues that God's existence is incompatible with the existence of moral obligations; the second argues that ordinary morality requires the existence of moral obligations. These conclusions are incompatible, so something must give.

For most theists, the attachment to ordinary morality is significant: they do not want to say that we can stand idly by when great suffering is taking place. But neither do they wish to give up belief in God. As a result, they are likely to focus their critical faculties on the first bit of the argument, the "God implies no moral obligations"-bit. There must, they reason, be something wrong with that inference.

To see what that something might be, let's restate the core of this part of the argument (omitting some of the supplementary premises discussed in part 1).

- (1) God exists (or "I believe that God exists").

- (2) Necessarily, God only allows undeserved, involuntary suffering if it produces a net benefit for the sufferer (principle of Theodical Individualism).

- (3) Therefore, we never have an obligation to intervene to prevent suffering.

Obviously, (1) is immune to challenge by theists. So the problems, if they exist, must lie elsewhere. Indeed, we can distinguish two lines of attack: (i) argue that accepting the principle of Theodical Individualism (TI) does not absolve us of obligations to prevent suffering; or (ii) argue that we need not accept the principle of TI.

Maitzen considers a range of such objections, some more important than others. Let's go through them systematically (FYI: I'll be numbering the responses and counter-responses as I go along because I'm going to present an argument map at the end; in case you get confused the numbering builds on that already presented in part 1).

2. Does TI really imply the absence of moral obligations?

The first set of objections are happy with the principle of TI, but do not accept that this drains us of all sense of moral obligation. Two arguments are relevant here.

a. Strong Deontologism

The first I shall call "strong deontologism". This argues that our knowing that something will benefit someone does not absolve us of certain duties we may owe them. The following hypothetical scenario makes the point (taken from Maitzen's article):

The first I shall call "strong deontologism". This argues that our knowing that something will benefit someone does not absolve us of certain duties we may owe them. The following hypothetical scenario makes the point (taken from Maitzen's article):

Suppose I have promised to pay John $1,000 for some work he did for me, but I learn that John's uncle is about to leave him $1,000,000 on the condition that John doesn't have even $1,000 of his own. I inform John of this, but John, who hates his uncle and doesn't want anything from him, insists that I pay him as I promised to do.The strong deontologist would argue that in this situation our obligation to pay John survives our knowing he would otherwise receive a greater reward.

There are three things to be said in response to this. First, the obligation in the described scenario arises from the human institution of promising. Maitzen's argument relies on obligations to prevent suffering that do not arise from promises. Second, in the described scenario we might be able to see how John could be better off by rejecting the larger sum (damage, say, to self-respect). We usually don't have that ability when dealing with instances of great suffering. Third, a crucial aspect of the described scenario is John's volunteering to forego the money. It would be difficult to see how an obligation could survive if John did not volunteer to do this.

b. The "Stump" Response

The second argument comes from one of the chief theistic philosophers who tries to defend TI, Eleanore Stump. She makes two points. First, that God decides what is the appropriate amount of suffering for each individual. So all suffering is prima facie evil since we don't know how much is appropriate for the individual in question. Thus, we should try to eliminate any suffering we happen to come across. Her second point is that relieving a sufferer is likely to be beneficial to the character of the reliever.

Two comments are apposite here. First, at best, Stump has provided us with a permission to intervene, not an obligation to intervene. Second, he comment about the benefit to the character of the reliever is out of bounds: the whole point of TI is that the benefit must accrue to the person who suffers.

In sum, neither of these attempts to reconcile TI with the existence of moral obligations works. I'll summarise these arguments as follows:

- (8) Strong deontologism suggests that we can still owe duties to someone even when their observance makes the person worse off (John and his uncle example).

- (9) There are significant disanalogies between the case of John and his uncle, and the examples of obligations to intervene to prevent suffering: (a) it relies on the institution of promising; (b) we can imagine some greater benefit accruing to John; and (c) John volunteers to forego the money.

- (10) The Stump response: we still have a prima facie duty to intervene, and interventions probably improve the character of the intervener.

- (11) At best, Stump has provided us with a permission to intervene and her claim that the intervention might benefit the intervener is a contradiction of TI.

3. Is God Bound by TI?

We move on then to consider the second set of objections to Maitzen's argument. This set focuses on whether God is bound by the principle of TI. Three arguments arise suggesting he might not be: (i) in order to realise the good of libertarian free will he can abandon TI; (ii) heaven swamps everything; and (iii) according to some theologies, not even God has knowledge of the future.

i. Libertarian Free Will

As Maitzen notes, the idea that libertarian free will is a such an unqualified good that God might be justified in giving it to human beings, even though this may lead to great suffering, is a popular one. It is popular as an objection to the problem of evil and popular as an objection to the type of argument Maitzen is trying to make. Given its popularity, it is worth spending quite a bit of time discussing it.

Maitzen thinks the libertarian free will objection fails for three reasons: (a) libertarian free will is not an obviously coherent concept, nor the only morally valuable type of free will; (b) it is not clear that libertarian free will has a positive intrinsic moral value or that it is a value promoted by the God of the bible; and (c) ordinary moral practice, as embodied in the criminal law, does not seem concerned with libertarian free will. Let's go through each of these reasons at sufficient length.

a. The Coherence and Value of Free Will

As regards the coherence of libertarian free will, I would be willing to go quite a bit further than Maitzen: I would say that libertarian free will is almost certainly not a coherent concept. Allow me to explain.

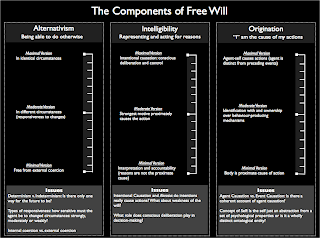

As Henrik Walter points out in his good, if poorly translated,* book The Neurophilosophy of Free Will, when people talk about "free will" they seem to be referring to a human capacity with three components: alternativism, intelligibility and origination.

By "alternativism" is meant the capacity to do otherwise than one actually did. So to say that we acted freely at some moment in the past, we must be able to say that it was possible for us to have made different decisions at those moments.

The alternativism-component of free will is subject to a number of interpretations, ranging from weak, to moderate, to strong. According to the strong interpretation, the capacity to do otherwise must hold even if circumstances were exactly the same; according to the weak interpretation, the capacity to do otherwise need only involve an ability to respond to different circumstances ("if things had been different, I would have done X").

By "intelligibility" is meant the capacity to represent and act for reasons. So it is not enough to say that we could have done otherwise, we must also be able to say that we acted for reason X, Y or Z.

Like alternativism, the intelligibility component of free will is subject to weak, moderate and strong interpretations. According to the strong interpretation, the reasons must be causally involved in the production of behaviour. This is what happens in the classical theory of intentional action. According to the weak interpretation, it is enough if the reasons and the behaviour have some common causal origin (as in Daniel Wegner's theory of the will).

By "origination" is meant that "you" are the cause of your decisions. In other words, it is not enough that intelligible decisions simply happen at random, they must be caused by a person or agent.

Again, like the other components, this component is open to weak, moderate and strong interpretations. According to the strong interpretation, actions must be caused by an ontologically unique entity known as the "agent". This agent is not reducible to causal psychological processes, it is something wholly distinct. According to the weak version, the agent is an abstraction from these psychological processes.

This component-view of free will is illustrated below (a heavily modified version of something found in Walter's book).

With that background in place, we can state simply the problem with the concept of libertarian free will: it holds to strong interpretations of all three components and it is not clear that this is possible.

Look at the origination component: libertarians want the agent to be the ultimate originator of action. It is no good, they will say, if actions are caused by preceding psychological states, because then we will need to ask about the causal history of those states, and before you know it you are caught in a problematic regress: it will seem as though "you" can never be responsible for your actions. But, if actions are not caused by underlying psychological processes, it is not at all clear that they can be intelligible in the strong sense.

Similar arguments apply to the strong interpretation of alternativism: libertarians want you do be able to otherwise than you did, in the exact same circumstances, but it appears that this type of alternativism would amount to arbitrariness. And arbitrariness would seem to defeat intelligibility and ultimate origination.

We could explore further problems, but the point is made.

Weaker accounts of free will are possible, and they are morally valuable. My own preferred version is an elaboration of the account developed by John Martin Fischer and Mark Ravizza in their book Responsibility and Control.

Their theory utilises weak to moderate versions of each component: all that is needed for moral accountability is that the mechanism producing human behaviour is capable of recognising and reacting to reasons, while at the same time being owned by a coherent personal narrative. They argue that this version can accommodate most of our ordinary moral practices.

b. Intrinsic Value and Biblical Support?

Maitzen's next argument against the libertarian objection is a two-parter. First he suggests, following Derk Pereboom, that libertarian free will does not have an intrinsic positive value. Pereboom's point is that in evaluating the morality of an evil action, the evildoer's freedom is a "weightless consideration". We don't say that Adolf Hitler's libertarian free will made his actions a little bit better than they would have been if they were pre-determined.

Second, the notion of libertarian free will as an intrinsic good that God cannot interfere with does not have biblical support. In two Bible passages (Exodus 14:8a and Romans 9:18) God "hardens hearts" and influences how people behave.

c. Libertarian Free Will is not a feature of Ordinary Moral Practices

Maitzen's final attack on the libertarian objection focuses on its absence from our ordinary moral practices. Here, we look to the operation of the criminal law (Anglo-American or Common Law versions) and see that libertarian free will is not a relevant consideration in the ascription of criminal responsibility.

Since Maitzen's claim intersects almost perfectly with my own area of research, I feel I can comment intelligently on it. On the whole, I think Maitzen is right: the criminal law is not interested in establishing that a defendant acted with libertarian free will. It is really only interested in establishing that the defendant was (and is) capable of recognising and responding to legal norms.

This is clearly illustrated by the operation of the defence of insanity. Legal insanity comes in two main varieties: cognitive and volitional. The cognitive version dominates in the US and was originally set out in the M'Naghten Rules. According to these rules, a defendant (even one with a recognised mental illness) will be held criminally liable unless they can show that at the time of the offence they did not know the nature and quality of the action they performed, or that it was legally wrong.

The volitional standard is not that popular anymore, although it is used my home country. It holds that a defendant will not be held responsible if they suffered from an "irresistible impulse" at the time of the offence. This might, on its surface, appear to be a concession to the libertarian position, but it isn't. What is meant by "irresistible impulse" is an impulse that does not respond to the presence of legal norms. Responsiveness of this sort does not depend on libertarian free will.

Of course, there has been plenty of controversy in this area. Many have tried, over the past two centuries at least, to argue that criminal responsibility makes no sense without libertarian free will, and since libertarian free will is wrong, we should abandon the traditional system of criminal justice. I think what is remarkable is that, despite occasional flip-flopping, the system of criminal justice has repeatedly rejected these arguments.

A good, if somewhat dated, article covering these issues is here (subscription required).

So to sum up: the libertarian free will objection is not successful.

ii. Heaven Swamps Everything

A second suggestion is that heaven is so wonderful that it manages to compensate people for any suffering they might experience in life, even if that suffering is in no way necessary for attaining the reward (which it isn't if we stick to the original definition of TI).

So the victims of systematic child abuse could undergo undeserved and involuntary suffering that is not necessary in order for them to achieve a heavenly reward. Nonetheless, the fact that they may ultimately receive that reward would compensate them for their suffering. Indeed, we might even say that because the reward is so great, people are likely to retrospectively consent to whatever suffering they endured.

Maitzen argues that not only does this conflate compensation with justification, it would also seem to erode any sense of moral obligation. Again, ordinary moral practice would not deem child abuse less worthy of condemnation and prevention if the children who suffered it retrospectively consented to it.

iii. Open Theism

The final objection comes from a branch of theology that deems it impossible for God to hold to TI. Why? Because not even God has knowledge of that part of the future that is dependent on the libertarian free choices of human beings.

Three responses are apposite. First, we have already seen that libertarian free will is not an obviously coherent concept. Second, God is still likely to have more foreknowledge than anyone else. So he would still prevent suffering that is highly unlikely to produce a net benefit. Third, if these objections fail, we could concede that the argument being made is only relevant to classical theism.

Okay, so that's everything. Let's summarise the arguments presented here and plug them into an argument map.

*I base that purely on my reading of the English version, which seems somewhat stilted. Perhaps it was like that in the original German. It is also worth noting that the three-component take on free will is not original to Walter.

i. Libertarian Free Will

As Maitzen notes, the idea that libertarian free will is a such an unqualified good that God might be justified in giving it to human beings, even though this may lead to great suffering, is a popular one. It is popular as an objection to the problem of evil and popular as an objection to the type of argument Maitzen is trying to make. Given its popularity, it is worth spending quite a bit of time discussing it.

Maitzen thinks the libertarian free will objection fails for three reasons: (a) libertarian free will is not an obviously coherent concept, nor the only morally valuable type of free will; (b) it is not clear that libertarian free will has a positive intrinsic moral value or that it is a value promoted by the God of the bible; and (c) ordinary moral practice, as embodied in the criminal law, does not seem concerned with libertarian free will. Let's go through each of these reasons at sufficient length.

a. The Coherence and Value of Free Will

As regards the coherence of libertarian free will, I would be willing to go quite a bit further than Maitzen: I would say that libertarian free will is almost certainly not a coherent concept. Allow me to explain.

As Henrik Walter points out in his good, if poorly translated,* book The Neurophilosophy of Free Will, when people talk about "free will" they seem to be referring to a human capacity with three components: alternativism, intelligibility and origination.

By "alternativism" is meant the capacity to do otherwise than one actually did. So to say that we acted freely at some moment in the past, we must be able to say that it was possible for us to have made different decisions at those moments.

The alternativism-component of free will is subject to a number of interpretations, ranging from weak, to moderate, to strong. According to the strong interpretation, the capacity to do otherwise must hold even if circumstances were exactly the same; according to the weak interpretation, the capacity to do otherwise need only involve an ability to respond to different circumstances ("if things had been different, I would have done X").

By "intelligibility" is meant the capacity to represent and act for reasons. So it is not enough to say that we could have done otherwise, we must also be able to say that we acted for reason X, Y or Z.

Like alternativism, the intelligibility component of free will is subject to weak, moderate and strong interpretations. According to the strong interpretation, the reasons must be causally involved in the production of behaviour. This is what happens in the classical theory of intentional action. According to the weak interpretation, it is enough if the reasons and the behaviour have some common causal origin (as in Daniel Wegner's theory of the will).

By "origination" is meant that "you" are the cause of your decisions. In other words, it is not enough that intelligible decisions simply happen at random, they must be caused by a person or agent.

Again, like the other components, this component is open to weak, moderate and strong interpretations. According to the strong interpretation, actions must be caused by an ontologically unique entity known as the "agent". This agent is not reducible to causal psychological processes, it is something wholly distinct. According to the weak version, the agent is an abstraction from these psychological processes.

This component-view of free will is illustrated below (a heavily modified version of something found in Walter's book).

With that background in place, we can state simply the problem with the concept of libertarian free will: it holds to strong interpretations of all three components and it is not clear that this is possible.

Look at the origination component: libertarians want the agent to be the ultimate originator of action. It is no good, they will say, if actions are caused by preceding psychological states, because then we will need to ask about the causal history of those states, and before you know it you are caught in a problematic regress: it will seem as though "you" can never be responsible for your actions. But, if actions are not caused by underlying psychological processes, it is not at all clear that they can be intelligible in the strong sense.

Similar arguments apply to the strong interpretation of alternativism: libertarians want you do be able to otherwise than you did, in the exact same circumstances, but it appears that this type of alternativism would amount to arbitrariness. And arbitrariness would seem to defeat intelligibility and ultimate origination.

We could explore further problems, but the point is made.

Weaker accounts of free will are possible, and they are morally valuable. My own preferred version is an elaboration of the account developed by John Martin Fischer and Mark Ravizza in their book Responsibility and Control.

Their theory utilises weak to moderate versions of each component: all that is needed for moral accountability is that the mechanism producing human behaviour is capable of recognising and reacting to reasons, while at the same time being owned by a coherent personal narrative. They argue that this version can accommodate most of our ordinary moral practices.

b. Intrinsic Value and Biblical Support?

Maitzen's next argument against the libertarian objection is a two-parter. First he suggests, following Derk Pereboom, that libertarian free will does not have an intrinsic positive value. Pereboom's point is that in evaluating the morality of an evil action, the evildoer's freedom is a "weightless consideration". We don't say that Adolf Hitler's libertarian free will made his actions a little bit better than they would have been if they were pre-determined.

Second, the notion of libertarian free will as an intrinsic good that God cannot interfere with does not have biblical support. In two Bible passages (Exodus 14:8a and Romans 9:18) God "hardens hearts" and influences how people behave.

c. Libertarian Free Will is not a feature of Ordinary Moral Practices

Maitzen's final attack on the libertarian objection focuses on its absence from our ordinary moral practices. Here, we look to the operation of the criminal law (Anglo-American or Common Law versions) and see that libertarian free will is not a relevant consideration in the ascription of criminal responsibility.

Since Maitzen's claim intersects almost perfectly with my own area of research, I feel I can comment intelligently on it. On the whole, I think Maitzen is right: the criminal law is not interested in establishing that a defendant acted with libertarian free will. It is really only interested in establishing that the defendant was (and is) capable of recognising and responding to legal norms.

This is clearly illustrated by the operation of the defence of insanity. Legal insanity comes in two main varieties: cognitive and volitional. The cognitive version dominates in the US and was originally set out in the M'Naghten Rules. According to these rules, a defendant (even one with a recognised mental illness) will be held criminally liable unless they can show that at the time of the offence they did not know the nature and quality of the action they performed, or that it was legally wrong.

The volitional standard is not that popular anymore, although it is used my home country. It holds that a defendant will not be held responsible if they suffered from an "irresistible impulse" at the time of the offence. This might, on its surface, appear to be a concession to the libertarian position, but it isn't. What is meant by "irresistible impulse" is an impulse that does not respond to the presence of legal norms. Responsiveness of this sort does not depend on libertarian free will.

Of course, there has been plenty of controversy in this area. Many have tried, over the past two centuries at least, to argue that criminal responsibility makes no sense without libertarian free will, and since libertarian free will is wrong, we should abandon the traditional system of criminal justice. I think what is remarkable is that, despite occasional flip-flopping, the system of criminal justice has repeatedly rejected these arguments.

A good, if somewhat dated, article covering these issues is here (subscription required).

So to sum up: the libertarian free will objection is not successful.

ii. Heaven Swamps Everything

A second suggestion is that heaven is so wonderful that it manages to compensate people for any suffering they might experience in life, even if that suffering is in no way necessary for attaining the reward (which it isn't if we stick to the original definition of TI).

So the victims of systematic child abuse could undergo undeserved and involuntary suffering that is not necessary in order for them to achieve a heavenly reward. Nonetheless, the fact that they may ultimately receive that reward would compensate them for their suffering. Indeed, we might even say that because the reward is so great, people are likely to retrospectively consent to whatever suffering they endured.

Maitzen argues that not only does this conflate compensation with justification, it would also seem to erode any sense of moral obligation. Again, ordinary moral practice would not deem child abuse less worthy of condemnation and prevention if the children who suffered it retrospectively consented to it.

iii. Open Theism

The final objection comes from a branch of theology that deems it impossible for God to hold to TI. Why? Because not even God has knowledge of that part of the future that is dependent on the libertarian free choices of human beings.

Three responses are apposite. First, we have already seen that libertarian free will is not an obviously coherent concept. Second, God is still likely to have more foreknowledge than anyone else. So he would still prevent suffering that is highly unlikely to produce a net benefit. Third, if these objections fail, we could concede that the argument being made is only relevant to classical theism.

Okay, so that's everything. Let's summarise the arguments presented here and plug them into an argument map.

- (12) God can break TI in order to realise the good of libertarian free will.

- (13) Heaven Swamps Everything.

- (14) God cannot hold to TI because not even God has perfect knowledge of the future.

- (15) Libertarian free will is not obviously coherent.

- (16) Libertarian free will has no intrinsic moral value and is not biblically supported.

- (17) Libertarian free will is not relied upon by ordinary moral practices.

- (18) Heaven swamps everything confuses compensation with justification. Furthermore, retrospective consent cannot justify evil.

- (19) Three objections to open theism: (a) libertarian free will is not obviously coherent; (b) God would have more foreknowledge than anyone else and so would adhere to TI as best he could; and (c) perhaps Maitzen's argument is only relevant to classical theism.

*I base that purely on my reading of the English version, which seems somewhat stilted. Perhaps it was like that in the original German. It is also worth noting that the three-component take on free will is not original to Walter.

Friday, March 19, 2010

Maitzen on Ordinary Morality and Atheism (Part 1)

(I struggled to find an apposite image to accompany this post. I settled on this simply because I liked it)

I've previously discussed Stephen Maitzen's work on the implications of skeptical theism for morality. Over the next couple of posts I am going to take a look at the following article:

All of these arguments suggest that there is an incompatibility between ordinary moral obligations and standards (or moral autonomy in Rachels's case) and God's existence. Maitzen attempts something similar in his article.

I'm going to break the discussion of Maitzen's argument into two parts. This part presents the basic outline of the argument. Part 2 looks at some detailed objections to the argument along with Maitzen's responses to them.

1. Some Preliminary Issues

Before becoming embroiled in the intricacies of the argument a few preliminary observations are in order.

First, as with my previous discussion of Maitzen's work, I am going to try to illustrate the argument with an argument map. This means that during the substantive discussion I will pause to present a series of numbered premises and conclusions that I can plug into the diagram at the end. Please note that my numbering does not follow the numbering that Maitzen uses in his article. This may make it difficult to cross-compare, my justification for it is that I found it easier to understand the argument by doing it this way.

Second, the argument is really two separate arguments with incompatible conclusions. The first argument suggests that God's existence implies the absence of moral obligations. The second argument suggests that ordinary morality implies the presence of moral obligations. These conclusions are obviously incompatible.

This leads me to a third observation. Does Maitzen's argument (or indeed Bradley's or Stretton's or Rachel's) offer good support for atheism? Maitzen's article does present an argument that reaches the conclusion "God does not exist".

But, as per his comment below, this is intended merely to show that it is possible to go from ordinary morality to the non-existence of God. To be a true argument for the non-existence of God it would need to mount a full defence of ordinary morality, something which it does not try to do.

My own take on it is that the argument really presents a doxastic dilemma for the theist: either they believe in God or they believe in ordinary morality, they can't believe in both.

The idea is that the commitment to ordinary morality is too strong to give up, so belief in God must give way. This might provide support for George Rey's meta-atheist thesis, the argument that no one really believes in God. Based on his interview over at commonsenseatheism, this is something with which Maitzen agrees.

2. Theism Implies No Moral Obligations

The first, and most difficult, part of Maitzen's argument suggests that coupling theism with some standard resolutions to the problem of evil leads to the conclusion that there are no moral obligations.

a. Principle of Theodical Individualism

We begin by simply conceding that God might exist and then draw out some of the difficulties with accepting his existence. The major difficulty comes from what is called the principle of theodical individualism:

This principle of theodical individualism amounts to a constraint on how God can treat humanity. It is an accepted constraint on any resolution of the problem of evil. This may set some alarm bells ringing since the idea of a constrained God might be anathema to some theists. We can say several things in response.

First, this is a standard Kantian principle that highlights the moral impropriety of treating someone as a means to an end. So it suggests that we cannot cause a person to suffer greatly simply to improve the lot of other people. This is the type of thing we would expect of a morally perfect being (Maitzen gives a thought experiment to make this point).

If that seems to presume too much, we can always fall back on the fact that numerous theistic philosophers accept it anyway (e.g. Eleanor Stump, William Alston and Marilyn McCord Adams) and that it is their belief system with which we are concerned in the first place.

Another objection to TI, not explicitly discussed by Maitzen but clearly lurking in the background, would be an Ockhamist one. The Ockhamist would say that it is meaningless to speak of moral constraints on God because he is the one who gets to define those constraints. We can respond by pointing out that if one is an Ockhamist, one has already abandoned ordinary morality. So the argument does not apply.

We can say further that the Ockhamist will still have serious problems knowing if he/she has any moral obligations due to the somewhat cryptic nature of God's attempts to communicate moral standards to us.

b. Theodical Individualism + God = No Obligations

Maitzen argues that if we accept that God exists, and we accept TI, we must accept one of two things: (a) that we have no moral obligation to prevent suffering or (b) that our moral obligations are defined by God's commands.

Why would we have to accept that we have no moral obligations? Think about it: if TI is true, then all actual instances of suffering ultimately benefit the sufferer. If there is an ultimate benefit you have no obligation to prevent that suffering.

Take a simple example: childhood vaccination. The actual act of administering the vaccine might cause the child to suffer, but because vaccination is ultimately beneficial you are under no obligation to intervene to prevent it. The theist (who accepts TI) is in this position whenever they encounter suffering.

Now they might respond by saying there is nothing to stop them from intervening if they see fit. But this is merely to identify a permission to intervene not an obligation. As we shall see in a moment, ordinary morality suggests that we have genuine obligations to intervene in some situations.

We make this point even stronger if we wish. We can say that if all instances of suffering ultimately benefit the sufferer, we are permitted to actively cause suffering. Again, think about the vaccine example: those who administer the vaccine are permitted to cause the child some suffering because of the ultimate benefit that accrues. Is the same not true for the theist who accepts TI?

The other possibility is that a theist who accepts TI still has obligations emanating from God's commands. There are two problems with this. First, as discussed previously, God's commands are difficult to identify and difficult to extrapolate to novel circumstances. So it is not clear that they provide any reassurance to the theist who wishes to prevent suffering.

The second problem with this response is that it forces the theist into an uncomfortable position. On the one hand, they believe that God has commanded them to prevent suffering. And on the other hand, they believe that God has set things up so that all suffering ultimately benefits the sufferer. These beliefs do not a happy pair make.

Let's stop here and summarise the components of the argument to this point.

I've previously discussed Stephen Maitzen's work on the implications of skeptical theism for morality. Over the next couple of posts I am going to take a look at the following article:

"Ordinary Morality Implies Atheism" (2009) 2 European Journal for the Philosophy of Religion 107-126.The idea that ordinary morality has disturbing implications for theism has been aired before. For example, Dean Stretton's article "The Moral Argument from Evil" makes this point, as does Raymond Bradley's "A Moral Argument for Atheism", as does James Rachels's "God and Moral Autonomy".

All of these arguments suggest that there is an incompatibility between ordinary moral obligations and standards (or moral autonomy in Rachels's case) and God's existence. Maitzen attempts something similar in his article.

I'm going to break the discussion of Maitzen's argument into two parts. This part presents the basic outline of the argument. Part 2 looks at some detailed objections to the argument along with Maitzen's responses to them.

1. Some Preliminary Issues

Before becoming embroiled in the intricacies of the argument a few preliminary observations are in order.

First, as with my previous discussion of Maitzen's work, I am going to try to illustrate the argument with an argument map. This means that during the substantive discussion I will pause to present a series of numbered premises and conclusions that I can plug into the diagram at the end. Please note that my numbering does not follow the numbering that Maitzen uses in his article. This may make it difficult to cross-compare, my justification for it is that I found it easier to understand the argument by doing it this way.

Second, the argument is really two separate arguments with incompatible conclusions. The first argument suggests that God's existence implies the absence of moral obligations. The second argument suggests that ordinary morality implies the presence of moral obligations. These conclusions are obviously incompatible.

This leads me to a third observation. Does Maitzen's argument (or indeed Bradley's or Stretton's or Rachel's) offer good support for atheism? Maitzen's article does present an argument that reaches the conclusion "God does not exist".

But, as per his comment below, this is intended merely to show that it is possible to go from ordinary morality to the non-existence of God. To be a true argument for the non-existence of God it would need to mount a full defence of ordinary morality, something which it does not try to do.

My own take on it is that the argument really presents a doxastic dilemma for the theist: either they believe in God or they believe in ordinary morality, they can't believe in both.

The idea is that the commitment to ordinary morality is too strong to give up, so belief in God must give way. This might provide support for George Rey's meta-atheist thesis, the argument that no one really believes in God. Based on his interview over at commonsenseatheism, this is something with which Maitzen agrees.

2. Theism Implies No Moral Obligations

The first, and most difficult, part of Maitzen's argument suggests that coupling theism with some standard resolutions to the problem of evil leads to the conclusion that there are no moral obligations.

a. Principle of Theodical Individualism

We begin by simply conceding that God might exist and then draw out some of the difficulties with accepting his existence. The major difficulty comes from what is called the principle of theodical individualism:

Necessarily, God permits undeserved, involuntary human suffering only if such suffering ultimately produces a net benefit for the sufferer.This principle contains some important qualifiers: "undeserved" -- to placate those who might feel some suffering is deserved; and "involuntary" -- to placate those who think that people could volunteer to endure suffering. By using the modal operator "necessarily" the principle is designed to cover not only cases of actual suffering but also cases of counterfactual suffering (see Maitzen's comment below for more).

This principle of theodical individualism amounts to a constraint on how God can treat humanity. It is an accepted constraint on any resolution of the problem of evil. This may set some alarm bells ringing since the idea of a constrained God might be anathema to some theists. We can say several things in response.

First, this is a standard Kantian principle that highlights the moral impropriety of treating someone as a means to an end. So it suggests that we cannot cause a person to suffer greatly simply to improve the lot of other people. This is the type of thing we would expect of a morally perfect being (Maitzen gives a thought experiment to make this point).

If that seems to presume too much, we can always fall back on the fact that numerous theistic philosophers accept it anyway (e.g. Eleanor Stump, William Alston and Marilyn McCord Adams) and that it is their belief system with which we are concerned in the first place.

Another objection to TI, not explicitly discussed by Maitzen but clearly lurking in the background, would be an Ockhamist one. The Ockhamist would say that it is meaningless to speak of moral constraints on God because he is the one who gets to define those constraints. We can respond by pointing out that if one is an Ockhamist, one has already abandoned ordinary morality. So the argument does not apply.

We can say further that the Ockhamist will still have serious problems knowing if he/she has any moral obligations due to the somewhat cryptic nature of God's attempts to communicate moral standards to us.

b. Theodical Individualism + God = No Obligations

Maitzen argues that if we accept that God exists, and we accept TI, we must accept one of two things: (a) that we have no moral obligation to prevent suffering or (b) that our moral obligations are defined by God's commands.

Why would we have to accept that we have no moral obligations? Think about it: if TI is true, then all actual instances of suffering ultimately benefit the sufferer. If there is an ultimate benefit you have no obligation to prevent that suffering.

Take a simple example: childhood vaccination. The actual act of administering the vaccine might cause the child to suffer, but because vaccination is ultimately beneficial you are under no obligation to intervene to prevent it. The theist (who accepts TI) is in this position whenever they encounter suffering.

Now they might respond by saying there is nothing to stop them from intervening if they see fit. But this is merely to identify a permission to intervene not an obligation. As we shall see in a moment, ordinary morality suggests that we have genuine obligations to intervene in some situations.

We make this point even stronger if we wish. We can say that if all instances of suffering ultimately benefit the sufferer, we are permitted to actively cause suffering. Again, think about the vaccine example: those who administer the vaccine are permitted to cause the child some suffering because of the ultimate benefit that accrues. Is the same not true for the theist who accepts TI?

The other possibility is that a theist who accepts TI still has obligations emanating from God's commands. There are two problems with this. First, as discussed previously, God's commands are difficult to identify and difficult to extrapolate to novel circumstances. So it is not clear that they provide any reassurance to the theist who wishes to prevent suffering.

The second problem with this response is that it forces the theist into an uncomfortable position. On the one hand, they believe that God has commanded them to prevent suffering. And on the other hand, they believe that God has set things up so that all suffering ultimately benefits the sufferer. These beliefs do not a happy pair make.

Let's stop here and summarise the components of the argument to this point.

- (1) God exists (or, at least, "I believe God exists").

- (2) Necessarily God only permits undeserved, involuntary suffering if it ultimately benefitted the sufferer (principle of Theodical Individualism).

- (2a) This is a basic Kantian principle that we might expect of a morally perfect being.

- (2b) This is a principle that is consistent with orthodox theistic beliefs.

- (2c) The Ockhamist objection already accepts the incompatibility of theism with ordinary morality.

- (3) There are no moral obligations to prevent suffering.

- (3a) Vaccination example shows that obligations do not survive when we know that a benefit ultimately accrues to a sufferer. Theists are in this situation all the time.

- (3b) Permissions may survive, but they work both ways, i.e. we may be permitted to cause suffering.

- (4) Obligations emanate from God's commands.

- (4a) God's commands are difficult to identify and to apply.

- (4b) Believing both (i) God has commanded you to prevent suffering and (ii) God has set things up so that suffering produces a net benefit to the sufferer, is not easily reconcilable.

These will be put into the argument map at the end.

3. Ordinary Morality Implies Obligations

The second, and far easier, part of Maitzen's argument is that ordinary morality implies the existence of moral obligations. Maitzen does not define ordinary morality, or attempt to provide a concrete ethical theory that supports the existence of obligations. Instead, he takes the existence of moral obligations as a datum that is in need of an explanation, an explanation that cannot be rooted in theism.

Let's consider some cases that seem to support the genuine existence of moral obligations. First, consider the drowning friend example that I mentioned in a previous post. Here, your friend has fallen into the water, is incapable of swimming, and you are the only one in a position to save him. The question is whether you have an obligation to save him (assume there is no serious risk to yourself)? It seems obvious that the answer is "yes".

Even in situations where there is a risk to ourselves or where we are unqualified to prevent the suffering, there is an obligation to seek appropriate help. This is most apparent from criminal law cases where the court imposes liability on failures to act.

Later in his article, Maitzen suggests that the criminal law offers a reasonable insight into the demands of ordinary morality. As someone who researches the philosophy of criminal responsibility, I think that is about right (plenty of controversy though). Anyway, the criminal law doesn't impose a general obligation to intervene (where "general" means "applies to everybody"), instead it identifies specific situations in which an obligation arises. These include situations where you are the only person who knows about the suffering, or where you are a qualified official.

To give but one example, in the English case of Stone and Dobinson [1977] 2 All England Reports 341, a couple were held guilty of manslaughter for failing to seek professional help for their anorexic housemate. Because the anorexic woman lived with them they were held to have an obligation to help her even though she refused to eat. (The anorexic was the sister of the woman in the couple, but this was irrelevant to the finding of an obligation to seek help -- even if it was relevant it would not defeat the point that ordinary morality holds to genuine moral obligations).

So there are genuine moral obligations arising from ordinary morality. Now, as hinted at above, we might worry about the theoretical foundations of these obligations. But this is basically irrelevant to the argument being made. We are not concerned with which meta-ethical theory can account for these obligations; we are concerned with whether belief in God can account for them.

Let's summarise the components of this part of the argument:

- (5) Drowning friend thought experiment suggests that we have an obligation to prevent suffering in certain circumstances.

- (6) Legal cases, such as the anorexic housemate one, suggest that we have obligations to, at least, seek help to prevent suffering.

- (7) Therefore, ordinary morality gives rise to moral obligations to prevent suffering.

4. Ordinary Morality Implies Atheism

Okay, so now we are in a position to bring both strands of the argument together. The diagram below provides the relevant map. This follows the mapping procedure outlined at the end of this post.

As can be seen, conclusion (3) and conclusion (7) are in direct competition. And since conclusion (3) follows from belief in God, it seems that ordinary moral obligations cannot coexist with God. Thus, we have a doxastic dilemma for the believer.

In Part 2 we will consider more detailed objections to this argument.

Monday, March 15, 2010

Maitzen on Skeptical Theism and Moral Obligation (Part 2)

This post covers some of Stephen Maitzen's arguments concerning the incompatibility of skeptical theism and morality. Part 1 introduced us to the whole idea of skeptical theism. It outlined the dialectical context in which it arises and the problem it tries to solve (evidential problem of evil).

Skeptical Theism leads to Moral Paralysis

As we saw, skeptical theism is based on the following three premises:

- (11) We have no good reason for thinking that the possible goods we know of represent the entire domain of possible goods.

- (12) We have no good reasons for thinking that the possible evils we know of represent the entire domain of possible evils.

- (13) We have no good reasons for thinking that the entailment relations we know of between possible goods and permissible evils represent all such entailment relations.

These are clumsily expressed, but they amount to the following: we do not know enough about morality to say that no greater good arises from particular instances of suffering and pain. Taken together, these premises support the following conclusion:

- (14) God may have good moral reasons for allowing suffering or pain.

A number of authors (e.g. Graham Oppy, Michael Almeida and Stephen Maitzen) maintain that skeptical theism is too successful. If we were to embrace it, we would have to embrace a profound scepticism concerning the existence of moral obligation.

To see why they might think this, consider the following scenario. You and a friend are out fishing one afternoon. It is beautiful, balmy summer afternoon. The birds are singing, the fish are biting, life is good.

Suddenly, the weather takes a turn for the worse. A severe gust of wind knocks your friend into the water. He is not able swim. He flails desperately, taking large gulps of water as he does so. If you do nothing, his lungs will soon become flooded, and he will asphyxiate and die.

Here's the key question: do you have a moral obligation to intervene and save your friend's life? Assume, you are a good swimmer, trained in life-saving and that the rescue would be an easy one.

Most people would say that this is about as clearcut a case of a moral obligation as there is. But, argue Maitzen et al, this conclusion is not open to the skeptical theist. They have accepted that God may have moral reasons for allowing suffering, reasons to which we have no epistemic access. Remember, our knowledge of morality is incomplete, fallible and defeasible; God's knowledge is complete, infallible and final. What right have we to assume we should intervene in what could be part of God's greater plan?

These assertions help the critic of skeptical theism make the following argument:

- (14) God may have good moral reasons for allowing suffering or pain.

- (15) We often face situations where people are suffering and must decide whether or not to intervene, all the time accepting that our knowledge of morality is imperfect.

- (16) We can never have an obligation to intervene to prevent suffering (from 14 and 15).

In effect, this argument is saying that skeptical theism leads to a form of moral paralysis. How does the skeptical theist respond?

Skeptical Theist Responses

Maitzen notes that skeptical theists have responded to this argument in at least three different ways. We will give these numbers so that they can be put into the argument map at the end.

- (17) The moral paralysis argument assumes a consequentialist theory of moral obligation. That is, it assumes we gauge our moral obligations by guessing the likely consequences of our actions. There are other theories of moral obligation that do not face this problem e.g. deontological theories.

- (18) Moral obligation can survive the uncertainty or scepticism assumed by skeptical theists.

- (19) God's commands provide us with some access to the realm of value. From these commands we can work out at least some moral obligations.

Are these responses any good? Let's take them in turn.

The first counterargument is clearly fallacious. It is not the fault of the moral paralysis argument that consequentialism is being assumed: this was the assumption of the skeptical theist argument. It assumes that God can allow suffering if it produces some greater good. This is straightforwardly consequentialist reasoning. Skeptical theism does not suggest -- nor does anyone make the argument -- that God has some deontological duty to ensure that certain people suffer.

The second counterargument can be defeated with a counterexample. This is the "Skeptical Tribesman" example (Maitzen's, not mine):

Imagine that a well-armed tribesman walks into a jungle field hospital and sees someone (known to us as the surgeon) about to cut open the abdomen of the tribesman's wife, who lies motionless on the table. It looks to the tribesman like a violent attack, so he sees good reason to intervene and prevent the surgeon from carrying out the attack. But suppose that this tribesman has heard some of his fellow tribespeople talking about the wonders of "western medicine". They say it can heal people of terrible illnesses but that it often involves strange procedures.In this situation, the tribesman has reason to be sceptical about his usual moral obligations. Given this, can we still say he has an obligation to intervene to prevent the attack? Maitzen thinks not. Given his legitimate doubt, he no longer has an obligation to intervene. He may have a permission to intervene such that he would not be held responsible or punished for intervening; but he cannot be held to have an obligation to do so.

To the skeptical theist, we are all in the same position as the tribesman. And we are in this position all the time. Thus, our doubts about our moral knowledge, eliminate our moral obligations.

The third counterargument also faces insurmountable difficulties. We can take it that the idea is that God has given us commands that define a certain range of moral obligations. This range is unaffected by skeptical theism.

Maitzen points out three serious flaws in this idea. First, we are not very good at deciding what counts as one of God's commands. Indeed, there are disputes over whether certain passages of the bible constitute divine commands. For example, Jews maintain that Genesis 17:10 commands circumcision; Christians argue that this is not the case or that it has been superseded.

Additionally, people who claim to have received God's commands directly are given mixed reception. If they receive a command to give up gambling or drug addiction, they are treated kindly. If they receive a command to torture their children, we are less kind to them.

The problem is that none of the alleged commands are self-authenticating. What usually happens is that we assume we understand what is (roughly) right or wrong and use this as a basis for identifying something as "God's command". This is precisely the type of thing that skeptical theists claim we cannot do.

Second, and similarly, even when we have identified commands, we obey them selectively. This is readily apparent in the existence of a wide range of commands that are ignored. For example, the rules on breeding livestock, sowing seeds, and eating shellfish that are found in Leviticus; or the rules imposing the death penalty on disrespectful children, adulteresses and homosexuals.

It doesn't help to say, as some have, that these commands are specific to the cultural milieu of the ancient near east (ANE). To say such a thing is to presuppose a knowledge of morality that skeptical theists claim we do not have.

Finally, even if we have identified commands, they very often do not provide us with the type of moral guidance we need. The specific commands (such as those on cattle-rearing) are of limited significance. To generalise from them would require an insight into God's purposes that is anathema to the skeptical theist.

More general commands -- such as "love thy neighbour as thyself" -- are often difficult to apply in specific instances. Go back to the drowning friend example. Suppose I hate myself and had been planning to bring about my death through drowning. Does this mean I should leave my friend die? We'd probably say "no": we can't make that sort of decision for our friends. But to say this is to go beyond the ambiguity of the general command.

Let's summarise all these objections so they can be added to the argument map at the end:

- (20) Skeptical Theism assumes consequentialism; no one argues that God has a duty to allow suffering.

- (21) Skeptical Tribesman example shows that moral obligations cannot survive the type of uncertainty envisaged by skeptical theists.

- (22) We aren't very good at identifying divine commands.

- (23) We often selectively obey divine commands; this presupposes a familiarity with the realm of value.

- (24) Divine commands do not provide us with the type of moral guidance we need.

In conclusion, it seems as though a skeptical theist must be a moral nihilist.

This argument is mapped below.

Maitzen on Skeptical Theism and Moral Obligation (Part 1)

Stephen Maitzen is a professor at Acadia University (interviewed here). He has some interesting things to say about how theism undermines morality. I thought I'd cover his arguments over the next few blog posts.

I'm going to begin by killing the following two birds (articles) with the one stone:

At the outset, let me say something of major importance. For some silly reason, US English and Real English (the "Queen's" English) often use different spellings, e.g. "mustache" vs. "moustache", "maneuver" vs. "manoeuvre", and "skeptical" vs. "sceptical". Since "Skeptical Theism" names a philosophical position, I am going to reluctantly accept the inelegance of the American spelling for the remainder of this series.

Let me say something else of lesser importance. I am going to use this post to introduce a new system of argument mapping. It's not my invention or anything -- it is widely used in logic textbooks -- but it's the first time I've used it on this blog. I'll explain it at the end.

1. The Problem of Gratuitous Evil

I begin by outlining the dialectical context in which skeptical theism is invoked. Many people will be familiar with the problem of evil. It is a classic atheistic argument which highlights the incompatibility of the existence of a good god with the existence of evil. The problem comes in two versions: (i) logical and (ii) evidential. Let's ignore the logical version for now.

The evidential version accepts that God's existence may be compatible with some forms of evil. But this is only true if the evil produces some greater good. The problem is that there exist instances of gratuitous evil. That is, evil that does not produce any greater good. That type of evil makes the existence of God highly unlikely.

Maitzen uses the following example of gratuitous evil to ground his discussion of skeptical theism:

In any event, the evidential argument can be given the following formal statement:

I'm going to begin by killing the following two birds (articles) with the one stone:

"Skeptical Theism and Moral Obligation" (2009) 65 International Journal for the Philosophy of Religion 93-103

"Skeptical Theism and God's Commands" (2007) 46 Sophia 235-241Both articles make roughly the same claim: skeptical theism damages ordinary moral reasoning. To understand that argument we are going to have to do two things: (i) understand what skeptical theism is and why it is invoked; and (ii) explain how skeptical theism might be thought to undermine moral reasoning. Part 1 will cover the first topic; Part 2 will cover the second.

At the outset, let me say something of major importance. For some silly reason, US English and Real English (the "Queen's" English) often use different spellings, e.g. "mustache" vs. "moustache", "maneuver" vs. "manoeuvre", and "skeptical" vs. "sceptical". Since "Skeptical Theism" names a philosophical position, I am going to reluctantly accept the inelegance of the American spelling for the remainder of this series.

Let me say something else of lesser importance. I am going to use this post to introduce a new system of argument mapping. It's not my invention or anything -- it is widely used in logic textbooks -- but it's the first time I've used it on this blog. I'll explain it at the end.

1. The Problem of Gratuitous Evil

I begin by outlining the dialectical context in which skeptical theism is invoked. Many people will be familiar with the problem of evil. It is a classic atheistic argument which highlights the incompatibility of the existence of a good god with the existence of evil. The problem comes in two versions: (i) logical and (ii) evidential. Let's ignore the logical version for now.

The evidential version accepts that God's existence may be compatible with some forms of evil. But this is only true if the evil produces some greater good. The problem is that there exist instances of gratuitous evil. That is, evil that does not produce any greater good. That type of evil makes the existence of God highly unlikely.

Maitzen uses the following example of gratuitous evil to ground his discussion of skeptical theism:

In 1982 Charles Rothenberg lost a child-custody dispute with his ex-wife. As revenge, he kidnapped his six year-old son David, doused him in kerosene while he slept, and set him on fire. David was left with third-degree burns covering 90% of his body and despite numerous surgeries remains terribly disfigured.David Rothenberg's misery seems to exemplify the problem of gratuitous evil. Other examples could be added to show that the volume of gratuitous suffering is also problematic.

In any event, the evidential argument can be given the following formal statement:

- (1) God is perfectly good.

- (2) A perfectly good being would not allow evil to exist, unless it produced some greater good.

- (3) There are instances of gratuitous evil (e.g. the David Rothenberg case).

- (4) Therefore, it is unlikely that God exists.

Let's move on to consider typical responses to this argument.

2. Standard Theodicies and Responses

Theists usually respond to the problem of evil by constructing theodicies. These are frameworks that provide plausible moral reasons for God to allow evil to exist.

Here are some examples, all trying to provide a moral reason for allowing David Rothenberg to suffer in the manner described above:

- (5) Rothenberg deserved to be punished (retributivist rationale).

- (6) God's intervention would have undermined the good of libertarian free will.

- (7) The severe burning aided soul-making, both David's and his family's.

- (8) The suffering brought (short-term) attention to the problem of child abuse.

The problem with each of these theodicies is that they can all be defeated by equally plausible countervailing moral reasons.

- (9) Six year-old children such as David do not deserve to be punished (children are not full moral agents).

- (10) God has a moral duty to treat people as ends in themselves, not as means to an end (this defeats 6, 7, and 8).