A common claim in the philosophy of technology is that technologies can alter social values. That is to say, technologies can change both how we perceive and understand values, and the way in which we prioritise and pursue them. A classic example is the value of privacy. Some argue that the prevalence of surveillance technology, combined with the allure of convenient digital services, has rendered this value close-to-obsolete. When push comes to shove, most people seem willing to trade privacy for digital convenience. Contrariwise, there are those that think that the technological pressure placed on the value of privacy means that it is more precious than ever and that we must do everything we can to preserve it.

But how exactly does technology alter values? It must have something to do with the way technology mediates our relationship with the world around us. In this article, I want to briefly outline some of my own thinking on this topic. I do so in two parts. First, I argue that values exist in conceptual spaces, and that these spaces consist of internal conceptualisations and external conceptual relations. Within these conceptual spaces, values are always, somewhat, under pressure and open to disruption. Second, I argue that technology can have two main effects on these conceptual spaces: they can change the practical achievability of particular conceptualisations of a value, making it harder or easier to obtain; or they can change the priority ranking of a value relative to other external values. This can result in a number of different possible value changes.

The thoughts I elaborate here are distilled from previous work that I published with Henrik Skaug Sætra. We have written two articles on: (i) how technology changes the values of truth and trust and (ii) six different mechanisms of techno-moral change. Both articles are available in open access form. You can read them if you want to follow up on the ideas presented here. I should also add that there are other valuable contributions to the literature on technology and value change. These include the article by Jeroen Hopster and his colleagues on the history of value change, and Ibo van de Poel and Olya Kudina on pragmatism and value change (to name just two examples).

1. Values Exist in Conceptual Spaces

To start with, I suppose we must ask the question: What are values? There are many esoteric philosophical treatises on this topic. I will avoid getting drawn into their intricacies. For present purposes, I define values as things that are, in some sense, desirable, worth pursuing, and/or worth honouring. They are properties of events, states of affairs or people that make these things good and worthwhile. Freedom, pleasure, justice, friendship, sexual intimacy, cooperation, truth, fairness, love, knowledge, beauty are all classic examples of values. There are also disvalues, which are simply the opposite of values: things that are to be avoided, rejected, dishonoured. They are properties of events, states of affairs and people that make them bad.

The metaphysical grounding of values is not something I will discuss in this article. For the purposes of understanding technology and value change, we do not need to take a stance on this matter. For this inquiry, values can be understood in a descriptive and sociological sense: what is it that people say they value? What sort of values are revealed through their behaviour? How do these social facts change over time? Changes in social values may or may not track some ideal sense of values. This does not mean, however, that inquiry into technology and value change is irrelevant for understanding ideal values. It could be that technology pushes people closer to or further away from ideal values. It could also be that technology opens up or allows us to discover new ideal values. It all depends on the effect that technologies have on the conceptual space of values.

That's enough scene-setting. What about this conceptual space of values? This is an abstract space, not a tangible one. It is a bit like the space of possible novels or possible design specs for cars. The conceptual space of values is vast. I suspect it is theoretically infinite insofar as virtually anything could be a value under the right conditions. Nevertheless, for practical purposes, the space is more limited. Most societies have sets of basic values. Many of these basic values are shared, more or less, across most cultures.

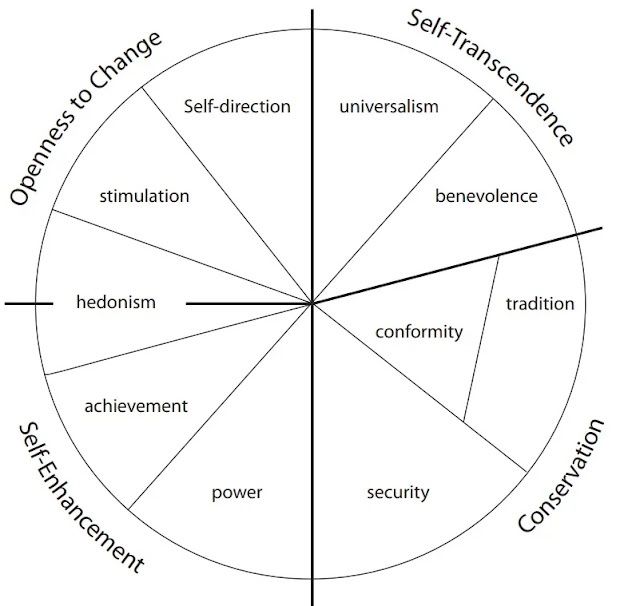

There have been various anthropological, psychological and philosophical attempts to identify a core set of basic values. The philosopher Owen Flanagan, for instance, has written about the shared virtues (kinds of value that inhere in individuals) across Western and Eastern cultures. The anthropologist Donald Brown has created a list of 'human universals', based on a cross-comparison of cultures. While this list encompasses many features of human society, it includes values such as play, generosity, responsibility, communality, friendship and so on. More systematically, the psychologist Shalom Schwartz has developed a theory of basic human values. He argues that there are ten individual values shared across most cultures. These values are categorised into four main domains: self-transcendence values, openness to change values, self-enhancement values and conservation values. Schwartz claims that this theory has a good deal of empirical support. The image below summarises his ten values.

In addition to these academic efforts at identifying a core set of basic values, there are projects in the political/legal realm that do something similar. For example, international human rights documents, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, could be viewed as attempts to identify and protect a basic set of human values (insofar as rights typically protect values).

I could go on, but I won't. This small sample of examples suffices for the point I wish to make: although the conceptual space of values is vast, it may be possible to make it more manageable by positing a list of basic values. Some people resist this idea. They think that universalising theories, such as those developed by Brown and Schwartz, simplify the messy complexity of human societies and underplay the real and substantive differences.

Although I lean in favour of universalisation, there is no need to take up a controversial position on the credibility of these theories here. Even if one accepts them, one is not obliged to accept that every society takes the same attitude or stance toward these values. Each theory posits a plurality of values. Societies (and individuals) can vary in how they order and rank these values, and how they deal with tradeoffs between the values. So, for example, if you accept Schwartz's idea that there are ten basic values, and that these values can be ranked in any order, there are (correct me if I'm wrong) 10! possible orderings of value. That's a lot of possible variation (over 3 million). Furthermore, nothing prevents you from adding to this list of basic values with more specific or unique values, relevant to particular societies.

In any event, what really matters for the inquiry into technology and value change is not getting precise about the number of values, nor demarcating the limits of the conceptual space of values. What matter is that values are, or at least are perceived to be, plural (there are many of them). A single value thus exists within a conceptual space of other values. The precise identities of these values matters less than their plurality.

2. How Values Change Within Conceptual Spaces

Turning then to value change, within the conceptual space of values, there are two main dimensions along which a single value can vary:

Internal dimension: How we conceive of or understand the individual value can vary, i.e. our particular conceptualisation of the value can vary.

External dimension: How the value relates to other values can vary, e.g. how it is ranked or traded off against other values within the same conceptual space can vary.

Let's consider both of these forms of variation in more detail.

Philosophers will be familiar with the idea that values can have different conceptualisations. Freedom is a value, but the concept of freedom is vague. To render it more precise and meaningful, people offer more detailed conceptualisations of it. On a previous occasion, I highlighted the work of the intellectual historian Quentin Skinner on the different conceptions of freedom that have vied for attention in liberal societies since the 1600s. Skinner, like many others, divided them into two main groups: models of positive freedom (i.e. to be free is to authentically realise oneself) and negative freedom (i.e. to be free is to be free from the influence and control of others). Within the negative freedom conceptualisation, Skinner identifies two further sub-conceptions freedom as non-interference (to be free is to be free from the actual interventions of other people through force or coercion) and freedom as non-domination (to be free is to be free from the dominion or authority of others). Further breakdowns of each of these sub-conceptualisations are possible. For example, Christian List and Laura Vallentini have developed a 'logical space' of different possible conceptualisations of freedom. In essence, this is a two-by-two matrix suggesting that theories of negative freedom vary along two main dimensions, resulting in four different possible conceptualisations of that value. If you are interested, I discussed their model in a previous article.

The example of freedom illustrates the general phenomenon. For each value we care about, there are usually multiple possible conceptualisations of that value. This is true for values such as equality, love, and truth, just as much as it is true for freedom. This variation in the internal conceptualisations of a value matters because when we say that we care about a value, or a society commits to protecting that value in its constitution, it could mean very different things in practice. Which conceptualisation of the value wins out or dominates could vary across cultures and times. Shifting between different conceptualisations of the same value is one form of value change.

What about the external dimension? This is more straightforward. Single values (or their more precise conceptualisations) sit within plural spaces of other values. We are not just committed to freedom; we are also committed to equality. We are not just committed to love and pleasure; we are also committed to hard work and truth. Questions arise as to how we ought to promote or honour all these different values. Is it possible to promote or honour them all with equal zeal? Must we prioritise some over others? Are there genuine cases in which values conflict and we must pick and choose? In the midst of a pandemic, when the risk of death from infectious disease is high, is it okay to prioritise public health and well-being over freedom? Or is this a false dichotomy? Figuring out the answers to these questions is, I believe, an ongoing struggle for all societies. Even when there is temporary agreement reached on how to balance or prioritise values, this can be easily disrupted by changes in circumstances (natural disasters, war and, of course, new technologies).

Once we appreciate the complexity of the conceptual space of values, it is easier to appreciate the phenomenon of value disruption. Most values are subject to internal dispute as to their correct conceptualisations. Furthermore, most values must fit into a wider network of other values, with which they are not always compatible. As such, values are never really in a settled equilibrium state. It's more like there is constant Brownian motion in the conceptual space of values. Disruption is never far away.

3. How Technology Disrupts Values

Finally, we come to the question of how technology disrupts values. If you accept the argument to this point, you accept that values are always somewhat apt for disruption. They are never as stable nor settled as they may seem. Consequently, it may not take much for technology, particularly new technologies to unsettle the present equilibrium. I believe that there are two main ways in which this can happen.

The first is that technology can affect how salient and practically achievable a particular conceptualisation of a value is. This is a form of internal value disruption.

An example might be the affect of artificial intelligence on different conceptualisations of the value of equality. Broadly speaking, there are two main conceptualisations of equality: equality of outcome and equality of opportunity. These conceptualisations are not necessarily incompatible, but they are, in practice, in tension with one another. Equality of outcome is about making sure that everyone gets a roughly equal (or equitable) share of some social good, e.g. wealth, healthcare, housing. Equality of opportunity is about giving everyone a roughly equal chance to compete for desirable social opportunities (jobs and education being the most obvious two). Equality of opportunity is sometimes favoured over equality of outcome on the grounds that forcing everyone to have an equal share of some good is either impractical or impinges upon other rights and entitlements. At present, most societies pursue a mix of policies aimed at both types of equality, but most liberal societies tend to prioritise opportunities over any strict form of equal outcomes.

How might AI affect this? In a recent paper, I looked at a number of different scenarios, focusing in particular on the impact of generative AI on how we think about equality. On the one hand, I argued that recent empirical tests of the impact of generative AI on workplace productivity suggest that the technology is of greater benefit to less-skilled, less educated and less experienced workers (read the paper for a fuller review of the current empirical basis for this claim, with some important caveats). This suggests that generative AI might assist with the practical achievability of equality of opportunity, providing for a way to level the playing field at work over and above (and complementary to) existing forms of education and training. Thus, equality of opportunity is likely to be seen as more desirable and more practically feasible. That said, I also argued that this could be a short run disruption, particularly if AI comes to replace, rather than augment, many human workers. If that happens, then equality of opportunity (in its current form) may become less practically achievable because technology starts to suck up all the desirable workplace opportunities. This may force a reconceptualisation of equality of opportunity (i.e. focus on other kinds of desirable opportunity) or a switch to equality of outcome as the more practically achievable version of the value.

The second way in which technology could affect values is by changing the priority ranking of one value relative to another. This would be a form of external value disruption.

An example might be the effect of digital technologies, including AI, on the value of truth vis-a-vis other values such as tribal loyalty or individual psychological welfare. This is an example that Henrik and I discuss in more detail in our paper on the technological transformation of truth and trust. Very briefly, we argue that the pursuit of truth is an important social value and that truth is valuable for both instrumental and intrinsic reasons. But truth is always a somewhat unstable value since their can be uncomfortable truths (e.g. climate change) that conflict with individual and group preferences. Powerful people often have a reason to manipulate our perceptions of the truth to suit their own agenda; we often deceive ourselves by pursuing information that confirms our existing biases; and we often want to share the beliefs and opinions of our peers so as not to step out of line.

One danger with digital technologies is that they make it easier to manipulate and control the flow of information in a way that makes it more difficult to access the truth. Examples of this abound, but the obvious ones are the ways in which social media and the algorithmic curation of information push people into 'bubbles' and information silos, along with the ways in which AI facilitates the creation of hard-to-detect fake information (e.g. cheapfakes and deepfakes). These developments can make it harder for people to commit themselves to the pursuit of truth and more willing to trade the value of truth off against other more easily attainable values such as displaying tribal loyalty, virtue signalling to others and making themselves feel good by limiting their exposure to uncomfortable ideas. This could lead to a down-ranking of truth relative to other values.

These examples of value disruption are somewhat speculative, even though there is evidence for both of them. Nevertheless, I provide them here not because they are necessarily accurate but because they illustrate the general idea of how technology can disrupt the conceptual space of values.