I have been teaching about legal reasoning and legal argumentation for years. When I do so, I try to impress upon students that legal argument is both simple and complex.

It is simple because in every legal case there is, in essence, one basic type of argument at the core of the dispute between the parties. This argument works from a general legal rule to a conclusion about the application of that rule to a set of facts. Philosophers and logicians would say that the basic form of legal argument is a syllogism: a simple three-step argument involving a major premise (a general principle or rule), a minor premise (a claim about a particular case or scenario) and then a conclusion (an application of the general rule to the particular case).

Here is a simple conditional syllogism:

- (1) If roses are red, then violets are blue. (Major Premise)

- (2) Roses are red. (Minor Premise)

- (3) Therefore, violets are blue. (Conclusion)

My view is that legal arguments take on a similar conditional, syllogistic form. There is a legal rule that stipulates that if certain conditions are met, then certain legal consequences will follow. This is the major premise of legal argument. Then there is a set of facts to which that rule may apply. This is the minor premise of legal argument. When you apply the rule to the facts you get a conclusion.

In abstract form, all legal arguments look like this:

- (1) If conditions A, B and C are satisfied, then legal consequences X, Y and Z follow. (Major premise: legal rule)

- (2) Conditions A, B and C are satisfied (or not). (Minor Premise: the facts of the case)

- (3) Therefore, legal consequences X, Y and Z do (or do not) follow. (Conclusion: legal judgment in the case).

To give a more concrete example, imagine a case involving a potential murder:

- (1*) If one person causes another person’s death through their actions, and they performed those actions with intent to kill or cause grievous bodily harm, and they had no lawful excuse for those actions, then they are guilty of murder and may be punished accordingly.

- (2*) Cain caused Abel’s death through his actions and in doing so he intended to kill and acted without lawful excuse.

- (3*) Therefore, Cain is guilty of murder and may be punished accordingly.

Simple, right? Unfortunately it is not. Although this basic argument is the core of all legal disputes it is not the totality of those disputes. The problem is that legal rules don’t just show up and apply themselves to particular cases. There are lots of potential legal rules that could apply to a given set of facts. And there are lots of qualifications and exceptions to legal rules. You have to argue for the rules themselves and show why a particular rule (or major premise) should apply to a particular case. In addition to this, the facts of the case don’t just establish themselves. They too need to argued for and the law adopts a formalised procedure for establishing facts, at least when a case comes to trial.

In this two-part article, I want to examine some of the complexities of legal argument. I do so first by examining the different kinds of argument you can present in favour of, or against, particular legal rules (i.e. for and against the major premise of legal argument). Understanding these kinds of arguments is the main function of legal education. People who study law at university or in professional schools spend a lot of their time examining all the different ways in which lawyers try to prove that a certain rule should apply to a given set of facts.

Several authors have presented frameworks and taxonomies that try to bring some order to the chaos of arguments for legal rules. I quite like Wilson Huhn’s framework The Five Types of Legal Argument, which not only does a good job of reducing legal argument down to five main forms, but also identifies all the different ways of arguing for or against a legal rule within those five main forms. I’ll try to explain Huhn’s framework, in an abbreviated fashion, in the remainder of this article. I should say, however, that I have modified his framework somewhat over the years and I'm not entirely clear on which bits of it are his and which bits are my own modification. Most of it is his. Some bits are mine (and most of the examples are ones that I use in my teaching and not ones that come from Huhn's book).

1. Argument from Text

For better or worse, law has become a text-based discipline. There are authoritative legal texts — constitutions, statutes, case judgments and so on — that set down legal rules. Consequently, one of the most common forms of legal argument is to identify the case-relevant legal texts and then use them to figure out the relevant rule. This is the first type of legal in Huhn’s framework and perhaps the starting point for most legal arguments.

Here’s a real example. Suppose you punch someone in the face on a night out and they accuse you of assault. You get arrested and you hire a lawyer. You ask them whether you are likely to be found guilty or not. The first thing this lawyer is going to do is to look up the rule governing assault cases like this. In Ireland, this rule is to be found in Section 2 of the Non-Fatal Offences Against the Person Act 1997:

Assault Rule: A person shall be guilty of the offence of assault who, without lawful excuse, intentionally or recklessly: (a) directly or indirectly applies force to or causes an impact on the body of another, or (b) causes another to believe on reasonable grounds that he or she is likely immediately to be subjected to any such force or impact, (c) without the consent of the other. [Text modified slightly from the statute to make the consent condition of the offence a little clearer]

The lawyer will then plug this rule into an argument about your case. Depending on the facts, they may say that you are likely to be found guilty or that you acted with lawful excuse (say, self defence) and so are likely to get off.

But it’s not that straightforward. Text-based legal rules rarely are. The terms within the text need to be interpreted. Their true meaning, within the context of the case at hand, needs to be determined. Sometimes the meaning might be obvious or uncontroversial, but many times it is not. The Irish assault rule, for example, contains a number of vague or uncertain terms. What does it mean to apply force ‘directly or indirectly’? Punching someone in the face is direct force, surely, but what if you throw water in their eyes? Is that indirect force? Come to think of it, what is ‘force’ anyway?

Fortunately, the Irish statute answers some of these questions for us. Later on in Section 2 of the 1997 Act it tells us that force includes “(a) the application of heat, light, electric current, noise or any other form of energy, and (b) application of matter in solid liquid or gaseous form”. So that clears up some confusion. But other doubts remain. What does it mean to ‘recklessly’ apply force? What would a ‘lawful excuse’ be? There are answers to these questions though they are not always clear and it would require significant additional argumentation to confirm the true meaning of the rule in this case.

I won’t belabour the point. As Huhn points out in his discussion, all text-based arguments have to be supported by some kind of textual analysis, i.e. a premise that supports a particular interpretation of the rule. This means that text-based arguments tend to take the following general form:

- (1) The text setting down the legal rule states ‘If conditions A, B and C are satisfied, then legal consequences X, Y and Z follow”.

- (2) According to textual analysis T, A really means D, B really means E and C really means F.

- (3) Therefore, the relevant legal rule is ‘If condition A (meaning D), B (meaning E) and C (with meaning F) are satisfied then legal consequences X, Y and Z follow”.

How do you support a textual analysis? Huhn argues that there are three basic forms of textual analysis in law:

Plain Meaning: The text has an obvious plain meaning. Dictionary definitions support this as does publicly understood meaning. (i.e. it does not require any fancy textual analysis)

Canons of Construction: There is some specific rule of legal interpretation that can clarify the meaning of the rule. There are lots of these so-called ‘canons’ of construction. Examples include expressio unius est exclusio alterius (if you expressly mention one thing you exclude another) or ejusdem generis (when items on a non-exhaustive list are of a particular type then all other members of that list are assumed to be of the same type). You could dedicate years to studying all the different canons of construction and not wrap your head around them.

Intratextual analysis: A later part of the same text clarifies what the true meaning of the rule is. So, to repeat the previous example, a later subsection of the Non-Fatal Offences Against the Person Act 1997 clarifies what is meant by the term ‘force’. Sometimes intratextual analysis is more subtle than this, however. Sometimes it is a case of trying to make an entire legal text coherent and non-contradictory by implying a fuller meaning into an earlier part of the text.

How do you critique a textual analysis? Huhn argues that there are six basic forms of critique, two applying to each of the three forms of textual analysis:

- Argue that either (a) the text is ambiguous or uncertain and so does not have a plain meaning or (b) the text has a different plain meaning.

- Argue that either (a) the stated canon of construction does not apply to this type of legal text (some canons of construction apply to statutes or their derivatives and others to other kinds of legal text, e.g. contracts) or (b) there is a rival canon of construction that applies to this text and results in a different meaning.

- Argue that either (a) there is a conflicting inference to be drawn from the same text; or (b) there is a conflicting inference to be drawn from another text (which must be read with this one, e.g. a statute must be consistent with the text of a constitution since the latter is a superior source of law).

One of the great virtues of Huhn’s framework is his attempt to exhaustively catalogue not only the five main forms of legal argument but also the different ways in which to support or attack those arguments. We’ll see this as we discuss the four remaining types of legal argument.

2. Intent/Purpose-Based Argument

The next type of argument is the intent or purpose-based argument. This is a sub-species of textual argument where, instead of looking at the plain meaning or objective meaning of a legal rule, you focus on the intent or purpose behind the rule. This type of argument is commonly used in contractual interpretation where the court figures out the meaning of a contractual term by appealing back to the intentions of the people who wrote it. It is also used in statutory and constitutional interpretation when lawyers focus on the intent of the legislature when drafting a law or the intent of the ‘framers’ when drafting a constitutional text.

Here’s an example of an intent-based argument. There’s a famous US case called In Re Soper’s Estate. It was decided in Minnesota back in the 1930s. The facts are somewhat unusual. It involved a man called Ira Soper who was married to a woman called Adeline Westphal. They lived in Kentucky. Soper must have been unhappy because he faked his own suicide and ran off to Minnesota. While there, he assumed a new identity (John Young) and married another woman called Gertrude Whitby. Technically, since Soper/Young was not dead, his original marriage to Adeline was still valid. Furthermore, since it was an offence to be married to two women at the same time, this meant that Gertrude was not, technically speaking, his legal wife. This technicality becomes important to the case.

Young entered into business with another man called Ferdinand Karstens. To protect their interests in the business they signed up to an insurance contract (or rather assurance contract) that ensured lump sum payments to their spouses or next of kin in the event of one of their deaths and ensured that the business would be transferred to the other partner at the same time. Since the terms of this deal could apply to either partner and either of their spouses, it was worded in an abstract way. As follows (this is slightly modified from the original):

Upon the decease of either John W. Young or Ferdinand J. Karstens, the Company shall collect the proceeds of the Insurance Policies upon the life of such deceased Depositor, and shall deliver the stock certificates of the deceased partner to the surviving partner and it shall deliver the proceeds of the insurance on the life of the deceased partner to the wife of the deceased partner if living...

You can probably guess the rest.

Soper/Young really did die and his second wife Gertrude collected the insurance money. But then his original wife found out that he had faked his earlier ‘death’ and came along claiming that since she was still his wife she should receive the insurance money. The court had to figure out what the phrase ‘wife of the deceased partner’ meant in this context.

The majority judgment in the case decided that the phrase was ambiguous given the circumstances of the case. You had to look beyond the plain meaning of the text to the intentions of Soper/Young when signing the agreement to figure out what it really meant. If you did that, they argued that the meaning was clear: Gertrude (the second ‘wife’) was the intended beneficiary not Adeline. This verdict was disputed by a minority judgment which argued that it flew in the face of the plain meaning of the text. There is some logic to the minority judgment, but it is a complicated linguistic issue. Either way, the majority verdict is still a good example of an intent-based argument being used to justify a particular legal rule — in this case a contractual rule — being applied to a case.

Intent-based arguments have the following general form:

- (1) The legal text says ‘If A, B, C, then X, Y, Z’

- (2) The intention/purpose of the person/s that drafted the rule was that A means D, B means E and C means F.

- (3) Therefore, the applicable rule is ‘If A (meaning D), B (meaning E) and C (meaning F), then X, Y, Z’

To support an intent-based argument you need to introduce evidence of the intent or purpose behind the provision. Huhn suggests that there are four main ways of doing this:

Look to the text itself: sometimes texts explicitly state the intention behind them, e.g. some statutes include long titles or preambles that explicitly or implicitly state the intentions behind them.

Look at changes to the text over time: A history of amendments or revisions to a text might reveal the intent insofar as these amendments suggest a refinement of the text to better approximate the intentions of its drafters.

Look at the history behind the text: The text will have been produced in a certain historical context perhaps in response to a particular challenge or controversy. This might suggest a particular intent. For example, the meaning of the US Constitution is sometimes interpreted in light of the historical purpose of the War of Independence and the separation from the United Kingdom.

Look at commentaries on the text: Commentaries on the text at the time it was drafted or amended (e.g. parliamentary debates about a statute) might reveal intent.

Whenever you move beyond the strict wording of a legal text you are entering troubled waters. There is a view out there that lawyers and judges should concern themselves solely with the strict literal wording of the text. They should not add words that are not there or distort the literal meaning with their own preferences or ideas. Furthermore, the idea that some legal texts have intentions or purposes behind them is problematic since they are often drafted by groups of people that may lack a common intention or they may have been intended to provide timeless abstract principles for a society (this is a common argument made about constitutional texts - If you’re interested I have written a couple of papers about some of the philosophical problems with constitutional interpretation).

As much as people would like lawyers and judges to stick to the texts, the reality is that this practically impossible. Part of the reason for this is that we naturally seek intentions and purposes whenever we engage with the written word. It’s just part and parcel of the social and interpersonal nature of language. Furthermore, language is frequently ambiguous, vague or otherwise uncertain. You have to look beyond the text if you are going to make sense of it. Looking for intentions is a good starting point.

There are many ways to defeat intentional arguments. Huhn identifies four main forms of attack and they can work no matter what form of evidence is being introduced to support the argument:

- Show that the evidence (of whatever form) suggests a different intent or purpose behind the text.

- Show that the evidence of intent is not sufficient or is ambiguous or inconclusive.

- Show that the intent that is evidenced does not count because it did not come from a relevant authority/person (only people with legal authority count when it comes to intent/purpose).

- Argue that the people who wrote the rule could not have anticipated the current facts and so there is no intent guiding the application of the rule in this case.

3. Precedential Arguments

The common law system is famous for its use of case-based reasoning. Judges decide cases and in doing so they create rules that apply to those cases. Under the system of precedent, subsequent judges in subsequent cases have to follow the same rules if they think their cases are sufficiently similar to the older ones.

It’s a little more complex than that, of course. The system of precedent recognises a hierarchy between courts. The judgments of superior courts in the same jurisdiction have to be followed but the judgments of inferior courts do not. But even if there is no strict rule stating that previous judgments have to be followed, it is common for judges to look to previous cases for guidance or reassurance when deciding present ones. This is true even when there is an authoritative legal text (such as a statute or constitution) that clearly sets out the rule governing the present case. As we just noted, those texts need to be interpreted and are often ambiguous, vague or otherwise uncertain. Consequently, judges look for guidance from previous cases that interpreted and applied the same rule. Hence, precedential arguments are a core part of the law.

Precedential arguments are a form of analogical argument.* Judges examine the facts of two cases to determine if they are relevantly similar. If they are relevantly similar, they apply the same rule to the two cases (following the rule from the older/superior court case). If they are not relevantly similar, they might apply a different rule, perhaps one coming from another case, or one that they invent/modify to suit the circumstances.

Here is an example. In the English case of AG Reference (No 6 of 1980), two young people got into an argument in the street. They agreed to settle their dispute by fighting each other. One of them sustained bruising to the face and a bloody nose. They were charged with assault causing harm. The question before the court was whether consent could be a defence to this charge since the two people had agreed to the fight. The court held that consent could not be a defence to a charge of assault causing harm. There were some legitimate exceptions to such a charge, such as legitimately organised sporting events, or certain ceremonial/aesthetic rituals (tattooing, ear-piercing), that might otherwise involve activities that we could classify as assault, but this case did not fall within those exceptions. It was just an ad hoc street fight.

In the later English case of R v Brown, a group of men engaged in private, consensual acts of sexual sado-masochism. They were found out, arrested and charged with assault causing harm. Again, they argued that they should be exempted from this charge because they had consented to the acts. The court disagreed with them. They held that this case was like AG Reference (No 6 of 1980) (and some other similar cases) in that it did not fall within the range of legitimate exceptions to the offence of assault causing harm, and in that consent was not a defence to such a charge.

So, despite some obvious dissimilarities between the cases — one involved a public street fight; the other involved private consensual acts of sexual violence — the majority of judges thought there were relevant structural similarities between the cases that justified the application of the same rule.

Interestingly, there were subsequent cases that seemed similar to R v Brown but were distinguished from it by the courts. For example, in the case of R v Slingsby, a man sexually penetrated the vagina and rectum of his wife with his fist. He was wearing a signet ring at the time and as a result of this his wife was cut, developed septicaemia and died. He was charged with assault causing harm. The courts dismissed the charge on the grounds that this was a private, consensual sexual act that had the indirect consequence (and not the primary aim) of causing harm. This made it very different from R v Brown which involved acts whose primary intention was to cause harm (albeit as part of a sexual kink). Hence it was a legitimate exception to the rule. Similarly, in the case of R v Wilson, a man branded the buttocks of his wife with a hot knife, apparently with her consent. He was also charged with assault causing harm but this was dismissed on the grounds that tattooing and aesthetic adornment of this sort fell within the range of legitimate exceptions to the offence. Furthermore, the interests of marital privacy justified not getting involved. This, again, made the case relevantly dissimilar from R v Brown which did not involve married couples and did not involve tattooing.

You might disagree with this. You might think the cases are more similar than the judges suggest or that they are straining to find structural differences to support bigoted or intolerant views. That’s fine and that’s part of how we go about critiquing analogical arguments. Nevertheless, this sequence of cases provides a good illustration of how precedential/analogical arguments can work.

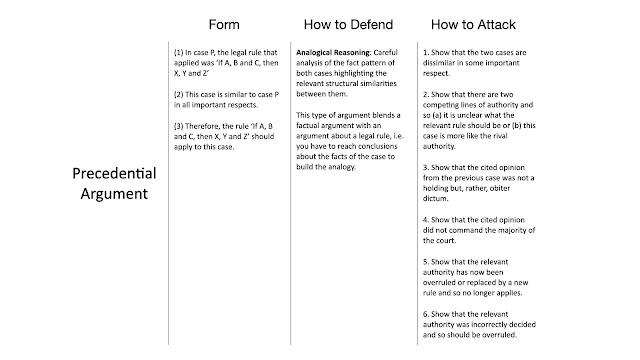

The general form of precedential arguments is as follows:

- (1) In case P, the legal rule that applied was ‘If A, B and C, then X, Y and Z’

- (2) This case is similar to case P in all important respects.

- (3) Therefore, the rule ‘If A, B and C, then X, Y and Z’ should apply to this case.

There is only one way to defend a precedential argument and that is by following the process of analogical reasoning, i.e. carefully review of the facts of each case, note the relevant similarities, and use this to justify the application of the same rule. Since no two cases are perfectly alike, this is always going to be an imperfect exercise and so analogical arguments are often open to challenge. Huhn suggests that there are six main ways to attack such arguments:

- Show that the two cases are dissimilar in some important respect.

- Show that there are two competing lines of authority and so (a) it is unclear what the relevant rule should be or (b) this case is more like the rival authority.

- Show that the cited opinion from the previous case was not a holding but, rather, obiter dictum. (In common law systems there is this idea that some portions of a previous judgment are legally binding — so-called ratio decidendi and some portions are not — so-called obiter dictum).

- Show that the cited opinion did not command the majority of the court.

- Show that the relevant authority has now been overruled or replaced by a new rule and so no longer applies.

- Show that the relevant authority was incorrectly decided and so should be overruled.

Of course, the relevance of some of these attacks will depend on the system of precedent in which one is operating and the way in which the previous case is being used.

I just want to make one final point about precedential arguments. Because of the way in which they work — building analogies between the fact patterns of two or more cases — this type of argument requires some established view of the facts of the case. You have to agree that the present case has certain features and that the previous case shared those features. If the facts are in dispute or are other than what the judge or lawyer claims them to be, this may block the application of the previous ruling. So this type of argument blends a defence of the major premise of legal argument with an implied defence of the minor premise.

4. Tradition or Custom-Based Arguments

The fourth type of argument is the argument from custom or tradition. This is an unusual one. We know, as a matter of fact, that societies follow rules even in the absence of a formal legal system. Hunter-gatherer bands, for example, have rules that members are expected to follow regarding the sharing of food and the treatment of others. These rules are rarely set down in an authoritative text. They are just habitualised within the society. It is sometimes claimed that the common law system has its origins in such traditions or customs. The early common law judges were not following precedent. There were no precedents to follow. They were, instead, recognising and adopting existing customary rules.

As law has become a more text-based discipline, with formalised procedures for creating and promulgating legal rules, the significance of customary or tradition-based rules has waned. Instead of pointing to customs, we point to texts to find the rules that govern our cases. Still, custom is an integral part of the law in certain areas. In contract law, for example, it is common to use customs within certain professions or locales to work out what the terms of a contract ought to be. Similarly, in international law, the customary behaviours of states toward one another is one of the primary sources of law. Finally, and perhaps most notoriously, there is no written constitution in the UK. There is, instead, a set of customary rules and norms that dictate how the state should be run. These are the main source of constitutional law in the UK.

Some philosophers and political scientists would go further than this. They would argue that since it is impossible to authoritatively and comprehensively write down every rule that governs society, the law must be supported by a significant body of unwritten, tacit, traditionary and customary rules. At some point in time, judges and lawyers must appeal to these rules in order to make legal arguments.

Here is an example of a custom-based argument in contract law. The case in question is the Irish case of Carroll v Dublin Bus. This involved a bus driver who was out of work for a period of time due to illness. He returned to work and was given an ordinary bus route. He disputed this on the grounds that it was a custom/tradition within Dublin Bus that drivers returning to work after a period of illness be given a ‘light’ or ‘rehabilitation’ route before being eased back into a normal work routine. The court agreed that this was indeed a custom within Dublin Bus and so he was successful. The court decided that this custom should be implied into the terms of his employment contract.

Custom or tradition based arguments take the following form:

- (1) The tradition/custom states that ‘If A, B and C, then X, Y and Z’

- (2) Evidence shows that the habits and customs of people in a given area/profession (etc) support the traditional rule ‘If A, B and C, then X, Y, and Z’

- (3) Therefore, the rule ‘If A, B and C, then X, Y and Z’ should apply to this case.

The key to a good custom-based argument is twofold: (i) show that the written law does not cover the facts that arise in the case or is necessarily incomplete without the custom; and (ii) provide evidence to show that people really are committed to that custom. There are a few ways of doing (ii). Huhn mentions the following:

Historical analysis: Show that the historical record supports the idea that people have always followed or endorsed this rule.

Recorded Opinion/ Commentary: Show that the evidence on public opinion (or the opinions of relevant sub-groups of the public) suggest that they agree to this rule.

A combination of methods can be the most effective.

There are three ways to attack a custom-based argument:

- Show that the alleged tradition does not exist, i.e. the evidence for the tradition is weak or incomplete or unpersuasive.

- Show that there have been competing traditions and so (a) it’s not clear which traditional rule should apply to this case or (b) the alternative traditional rule should apply to this case.

- Show that a new tradition is emerging which displaces the old traditional rule (this is a frequent problem with tradition-based argument since society is always changing and adapting to new realities).

5. Policy-Based Arguments

The final type of argument (according to Huhn’s framework) is the policy-based argument. This is perhaps the most contentious type of argument. It involves advocating for the application of certain rules on the grounds that they are good policy, or, conversely, arguing against the application of certain rules on the grounds that they are bad policy. This type of argument is controversial because some people think that lawyers and judges should not be engaged in policy-making, but the practical reality is that policy-based arguments are widespread in law, and they are often critical in the most contentious cases.

Policy-based arguments have two key steps to them. The first is an inquiry into the likely consequences or outcomes of applying a particular rule to the facts of the case (so, again, there tends to be some initial agreement on the facts though it is not as integral to this type of argument as it is to a precedential argument). The second is the use of some evaluative or normative theory to assess those consequences or outcomes. This evaluative theory can be drawn from multiple sources: economic theory, moral theory, and religious tradition are among the most commonly used.

In my experience, it is rare for courts to use policy-based arguments to simply create entirely new legal rules. Maybe that did happen back in the day. What’s more likely to happen nowadays is that there is some dispute as to which rule (or which interpretation of a rule) should apply to a case. To resolve this dispute, courts will examine the likely outcome of applying the rule to the case. If they think the outcome is consistent with their preferred evaluative theory, they will apply it. If not, they will look for an alternative rule (or an alternative interpretation of the rule).

Here’s an example. The English case of Re A (Conjoined Twins) is remarkable for a number of reasons. The facts are well-known. A pair of conjoined twins (referred to as Jodie and Mary in the case) were born in August 2000. Jodie was the stronger of the two. Mary was only kept alive by a common artery that she shared with Jodie. If left conjoined, they would both, almost certainly, die. If separated, Jodie would live and Mary would die. The doctors wanted to separate them. The parents objected. The case was referred to the courts for guidance as to whether it was legally permissible for the doctors to proceed with the separation.

There were many issues in the case. The chief one was whether the surgeons would be guilty of murder if they performed the surgery. Though there were disagreements among the judges, they agreed that the surgeons would be intentionally killing Mary by performing the separation (they would be intentionally causing her death through their actions) but that they did have a lawful excuse for doing so. What that lawful excuse was ended up being disputed between the judges. One judge analysed the case partly in terms of self-defence, but two of them agreed that the doctors could avail of the defence of necessity. In brief, they argued that what the doctors were doing was necessary, in the circumstances, to prevent the death of both twins and save the life of Jodie (it was the lesser evil).

The problem with this, however, is that previous case law suggested that the defence of necessity was not available to a charge of murder. One of the reasons for this limitation, suggested by commentators on the law, was that if it was a defence people might be too quick to appeal to it to sanction their own murderous acts. In other words, we might have an army of would-be murderers suddenly concocting situations of necessity in order to get away with murder. One of the judges in the case, Lord Justice Brooke, argued that this predicted outcome was unlikely to occur:

If a sacrificial separation operation on conjoined twins were to be permitted in circumstances like these, there need be no room for the concern felt by Sir James Stephen that people would be too ready to avail themselves of exceptions to the law which they might suppose to apply to their cases (at the risk of other people's lives). Such an operation is, and is always likely to be, an exceptionally rare event, and because the medical literature shows that it is an operation to be avoided at all costs in the neonatal stage, there will be in practically every case the opportunity for the doctors to place the relevant facts before a court for approval (or otherwise) before the operation is attempted.

This is an example of a policy-based argument. Brooke LJ is considering the possible outcome of applying the defence of necessity to this case and is arguing that it is unlikely to have negative consequences (it’s not going to give an easy excuse to would-be murderers). Hence, he is willing to apply the defence to this case. (Note: there are many other policy-based arguments in the judgment — this is just one example).

Policy-based arguments have the following general form:

- (1) The supposition/working hypothesis is that rule R (taken from text, intention, precedent or tradition) applies to this case.

- (2) If rule R applies to this case, good/bad consequence/outcome/moral fit X, Y, and Z will occur. (Prediction Premise)

- (3) We should adopt a rule with good consequences/outcomes/moral fit; we should not adopt a rule with bad consequences/outcomes/moral fit (Normative Premise)

- (4) Therefore, rule R should/should not apply to this case.

The key to defending a policy-based argument is to show (a) that the predicted consequence/outcome is likely to occur and (b) that it is consistent/inconsistent with the preferred evaluative theory. There are many different evaluative theories so there are many ways of trying to defend the normative premise of this argument. Still, in broad outline, we can say that there are two basic methods of evaluation. First, there is deontological evaluation where you check to see if the proposed legal rule is consistent with another rule drawn from your preferred evaluative theory (e.g. a secular moral theory such as Kantianism or a religious moral theory). Second, there is pure consequentialist evaluation where you check to see whether the consequences of the rule are good or bad according to the criteria of your preferred evaluative theory (does it promote economic growth? limit suffering? promote welfare and well-being? reduce crime? and so on)

Because of their contentious nature, and in particular because of the widespread disagreement about preferred evaluative theories, policy-based arguments are frequently attacked. Huhn suggests that there are six main methods of attack:

- Argue that it is not the job of the law to make these policy judgments (that’s a job for the legislature or the public).

- Show that the relevant evaluative theory actually supports an alternative rule.

- Show that although the policy is good, it is not served in this case (i.e. the prediction is false).

- Show that there is a competing policy outcome that should be preferred.

- Show that the alleged desirable/undesirable consequences will not follow from the rule.

- Show that policy considerations are not sufficiently strong to outweigh other legal arguments.

6. Conclusion

So there you have it. This is a brief overview of the five main ways of defending and critically analysing the first premise in any legal argument. I've summarised all the main ideas into a handy chart/table which you can download here, if you like.

* There are some legal theorists that claim that this is wrong. But in my experience they offer highly technical analyses of case-based reasoning that are divorced from how legal practitioners actually think it works in practice. It’s simpler, and in my view more accurate, to see precedential arguments as a species of analogical argument.

The conventional view seems to be that the principal difference between common law and civil law reasoning is that civil lawyers normally start with the principle and then try to apply it to the facts at hand (deductive reasoning) but that common lawyers do it the other way around (inductive reasoning). My view is that this is at best overdone and that all lawyers use both types of reasoning. Comments?

ReplyDeleteThe conventional view seems to be that the principal difference between common law and civil law reasoning is that civil lawyers normally start with the principle and then try to apply it to the facts at hand (deductive reasoning) but that common lawyers do it the other way around (inductive reasoning). My view is that this is at best overdone and that all lawyers use both types of reasoning. Comments?

ReplyDeleteThis was a very interesting read, many thanks to you for the write up. I've two suggestions regarding the content and two and a half suggestions regarding the form, which may further improve it; maybe you'd like to consider them:

ReplyDeleteRight at the beginning, where you show the general abstract form of a legal argument, your use of "(or not)" may be interpreted as to mean that, when the conditions are not met, the consequences do not follow. However, since your premise is "If A, then B" and not "If and only if A, then B", this interpretation would constitute a false contraposition. I am fairly sure that you know this distinction and it's only a minor point, I just thought that it may be beneficial to spell it out more precisely.

When you explain the concept of ejusdem generis, the formulation is not quite correct, though I'd say it is clear what you mean. Namely, there are no "other members of that list". Maybe write something akin to "[when items on a non-exhaustive list are of a particular type, then] the rule which utilizes that list is assumed to apply to all other members of that TYPE as well."

The first method of attack against a policy-based argument should be a bullet point, like the others.

The paragraph mentioning "AG Reference (No 6 of 1980)" is missing a "not". "[...], but this case did [NOT] fall within those exceptions."

(Maybe do a search and replace to change all occurrences of double spaces to a single space.)

Cheers

Thanks to my father who shared with me on the topic of this webpage, this weblog is in fact remarkable. Pas de vérification de crédit

ReplyDeleteFantastic article on blockchain and its regulatory challenges! As a Blockchain Lawyer, I can’t stress enough how important it is to have the right legal counsel in this space. At Cloudhaus Law, we provide specialized services as Cryptocurrency Legal Advisors, helping clients navigate smart contract issues, DeFi regulations, and more. Whether you're an established business or a startup, our team offers top-notch digital asset legal services tailored to your needs.

ReplyDeleteKeep sharing such informative blogs, if anyone wants legal assistance for business formation, they can surely go for Expungement Fairfax, they surely are the best one in the business.

ReplyDeleteWhen it comes to legal matters, having the right advisor can be the difference. Family, criminal, or civil cases, you require someone who is experienced, clear and committed. Top advocate Advocate Shrishti Rani of Patna boasts the strongest legal expertise and client-centric attitude.

ReplyDeleteShe is an expert in offering a broad spectrum of legal services, ranging from divorce to child custody, maintenance, domestic violence, property issues, and criminal defence. With a composed attitude and a keen legal mind, she makes sure that her clients are represented fairly and respectfully during the legal procedure.

Clients trust Advocate Shrishti Rani not only for her court advocacy but also for her sincere concern and practical guidance. Her success is founded on a platform of open communication, ethical behavior, and relentless case preparation. Whether you are grappling with a delicate family matter or a serious criminal allegation, her advice can be your best defense.

Read More:- https://advocaterani.com/

I tried a couple of tips you mentioned and honestly, they worked better than I expected. Looking forward to more such posts.paralegal service provider

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis clear breakdown of legal reasoning is insightful. Understanding these argument types is essential for any criminal defence lawyer, and firms like Marcellus Law use these strategies to build strong cases and protect their clients effectively.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete