According to Bernard Suits’s classic philosophical dialogue

The Grasshopper playing games represents the highest ideal of human existence.

The Grasshopper is set in a hypothetical post-instrumentalist future. That is: a future of technological abundance in which humans can have their every wish granted to them by smart machines. Need a house? In the world of the Grasshopper, you just have think about it and the mind-reading machines in the environment will build it for you. In this world, instrumental activity has been effectively limited. You don’t have to do anything in order to get something else. Activities are to be pursued strictly for their intrinsic merits.

This is, consequently, a world in which humans have nothing left to do but play games. One of the main functions of Suits’s dialogue is to provide a philosophically tractable definition of a ‘game’. These are defined as activities that humans voluntarily choose to perform and that interpose artificial obstacles between them and some arbitrarily chosen goal. Since all obstacles are artificial in a post-instrumentalist society, all activities are games. They can be fun to play, but they are ultimately inconsequential: nothing of value hinges on success in the game. You don’t earn money or gain access to other opportunities. You are playing the game purely for the hell of it.

The desirability of Suits’s game-playing utopia has been criticised over the years.

I have written about these criticisms before. In this post I want to look at another criticism of the idea. This one comes from a paper entitled ‘

Endless Summer: What kinds of games will Suits’ Utopians Play?’ by Christopher Yorke. It claims that Suits’s utopia runs into problems because it is

unintelligible. I’m going to offer a detailed reconstruction and analysis of this argument from unintelligibility over the remainder of this post.

1. The Argument from Unintelligibility

Yorke’s paper doesn’t set out the objection to Suits’s utopia with the clarity that I would like. If you read it, you’ll see that he presents a series of concerns, starting with one about the impossibility of designing games that would be sufficient to stave off boredom in the post-instrumentalist world, and building into a general objection to the very idea of a post-instrumentalist world. On my reading, these objections can be united under a common argumentative framework - the argument from unintelligibility. I think this captures the core of what Yorke has to say, but in presenting it in this way I am going to be deviating from the structure of Yorke’s article. So, be warned that from here on out you are getting my take on Yorke’s argument, rather than a pure summary, in what follows.

The argument from unintelligibility works like this:

- (1) In order to be rationally/motivationally compelling, a utopian project/vision must be intelligible (i.e. give some clear sense of how we get from here to there).

- (2) Suits’s utopia of games is not intelligible.

- (3) Therefore, Suits’s utopia is not rationally/motivationally compelling.

The surface structure of the argument is unfussy, but there is complexity buried beneath. Premise (1) is not something that is explicitly defended in Yorke’s article but I think it is implied and does some of the argumentative work. As it stands, I think that premise (1) is plausible. Classically, utopias are conceived as ‘blueprints’ for the ideal society. The most famous utopian work in the Western canon — Thomas More’s 1516 book

Utopia — is a detailed description of the organisation and functioning of a utopian society. The blueprint is supposed to guide us, to help us advocate for and realise political and social change. Of course, the blueprint model is not favoured by everyone. Some people prefer to conceive of utopianism as an ongoing process rather than a project that arrives at a stable end-state. But even if you prefer this

procedural or

horizonal approach to utopianism, you still need some clear sense of what the procedure is supposed to require. It’s not going to be compelling to ask people to sign up to something that is completely vague, unspecified or incomprehensible. So intelligibility looks like a must.

Suits’s utopia seems to fit, broadly, within the ‘blueprint’ class of theories. His book provides a sketch of a post-instrumentalist society and claims that it would represent the ideal of existence. Thus, it looks like he is following the classic utopian playbook and so should be held to the same standards: he should provide a vision that is rationally/motivationally compelling.

There is, however, an alternative interpretation of Suits’s book, one that is supported by Suits himself. Perhaps he is not trying to say that post-instrumentalism is desirable but, rather, that it is inevitable? If we look at general progress in technology to date, we see that it has primarily been about getting machines to do things on our behalf. If we perfect this technological progress, we will inevitably end up in a world in which machines can do everything we desire without requiring any effort on our part. We will then arrive at Suits’s hypothetical society. We will then be lucky that this society happens to coincide with what Suits calls the ‘ideal of existence’, but his goal is not to tell us how we are to get from here to there — that’s going to happen anyway. According to this interpretation, premise (1) does not apply to Suits’s argument.

The problem with this interpretation is that Suits is then trying to walk a very fine line. He is saying that his game-playing utopia is inevitable but that it will also be great. The latter makes it seem like something we should be getting behind: something that we should find rationally compelling. Furthermore, Suits suggests that there are certain things we should be doing to prepare for the post-instrumentalist reality, in particular we should start designing the games we will play to stave off boredom. This looks like a utopian project, one that needs some intelligibility if it is to be compelling.

If this is right, premise (1) does apply to Suits’s argument and we can move on to premise (2). This is the real nub of Yorke’s critique and it is defended in two different ways. We’ll look at both in what follows.

2. The Unintelligibility of Utopian Games

The first defence of premise (2) focuses on the nature of the games we will be playing in the post-instrumentalist society. Suits is clear that games will provide the difficulty and challenge that is needed to stave off boredom in this world, and he is clear that we need to start “the immense work of devising these wonderful games now”, but he is not clear on what these games will look like. This suggests to Yorke that the utopian games are epistemically inaccessible and hence unintelligible.

- (4) In order for Suits’s utopia of games to be intelligible we need to have a clear sense of what utopian games will involve (particularly since we have to start designing them now).

- (5) We have no clear sense of what utopian games will involve.

- (2) Therefore, Suits’s utopia of games is not intelligible.

Before we get into the main part of this argument we have to clear up a potential source of confusion. The concept of a utopian game is somewhat ambiguous. Given how he defines games (as the achievement of arbitrary goals through the voluntary triumph over artificial obstacles) and how he characterises the post-instrumentalist society, there is a sense in which any activity undertaken in that society counts as a game. In other words, all activities in the post-instrumentalist society are ‘games by default’. This includes things like building your own house, or hunting for your own food, or doing scientific research: since machines can do these things for you any attempt to do them for yourself would involve the artificial imposition of obstacles between you and a goal. These activities would not be games in any other society. These ‘games by default’ should be contrasted with ‘games by design’, which are deliberately designed to function as games, and are always and everywhere game-like.

You might think that one way for Suits to overcome the unintelligibility problem is to fall back on ‘games by default’; to say that we do have some clear sense of what utopian games will look like: they will look like the instrumental activities that we perform today. For what it is worth, this is how I always interpreted the utopia of games. I imagined that it would consist of many of the activities that motivate us today, performed for fun (for their intrinsic merits) rather than necessity. But Yorke resists this interpretation of the argument. He thinks it doesn’t account for what Suits actually says. In particular, he thinks that if you focus on games by default you can’t make sense of Suits’s worries about boredom in a post-instrumentalist society, nor his injunction that we ought to start the work of designing the games that the utopians will play. This suggests that games by design are necessary too.

The problem then is that Suits provides no guidance as to what these games will look like. You can read between the lines of his book, however, and find some guidance as to what they will

not look like. For example, Suits stipulates that in Utopia no one can be wronged or harmed. Yorke argues that this rules out immoral games:

So games that necessarily, in the course of playing them, incur irreparable physical harm upon their participants — such as Russian Roulette and Boxing — will be excluded from the utopian set. Similarly, games that require players to engage in immoral behaviors like bald-faced lying in order to play effectively — Werewolf and Diplomacy come to mind — will be off the menu.

(Yorke, 8)

Similarly, Suits argues that all interpersonal problems will be eliminated in his utopia, which suggests that all cheating or unsportsmanlike behaviour will be impermissible:

…in Suits’s utopia, his utopian games will not be ruined by the bad behavior of their players. Cheating, trifling, spoilsporting, bullying, and grousing behaviors will all be preemptively (if somewhat rather mysteriously) eliminated.

(Yorke, 8)

Finally, Suits says that the games cannot be boring. This, according to Yorke, rules out quite a large number of games:

Boring games would include soluble games (those with a dominant strategy that, once known, leave no opportunity for the exercise of meaningful player agency, like Tic Tac Toe), games of pure chance (those that leave no opportunity for the exercise of meaningful player agency because strategy and tactics cannot have impact on their outcome, such as Snakes and Ladders), and games of pure skill (like Chess — since utopians will have endless hours to devote to its study, and potentially live in a time ‘when everything knowable was in fact known’).

(Yorke, 9)

The problem is that once you rule out all of these kinds of game — immoral ones, ones that involve unsportsmanlike behavior and ones that are boring — you end up with a space of possible utopian games that is epistemically inaccessible to creatures like us. The utopian games are clearly going to be very different from the kinds of games we currently play, and we have no concrete idea of what they will actually involve. This leads to unintelligibility. That’s the essence of Yorke’s first argument

I have some problems with this argument. I think Yorke sets too high a standard on what counts as immoral and boring.

For me, the immorality of conduct depends largely on the context and the consequences. Boxing might be immoral if it entails, as Yorke insists, irreparable harm (though you might dispute this on the grounds that people can consent to such harm). But why assume that harm would be irreparable in Suits’s utopia? If we have reached a state of technological perfection would this not also involve medical perfection? Think about the world of Star Trek. I remember several episodes where crew members were injured playing games on the holodeck, only to have their injuries quickly healed by the advanced medical technology. If that becomes possible for boxing-related injuries, then I don’t see how boxing retains its immorality. Likewise, I think that within the context of game, behavior that would ordinarily count as lying or deception, can lose any hint of immorality, particularly if it is required for success in the game. Indeed, I would go further and argue that it is not even possible to ‘lie’ when playing a game like Diplomacy. The standard philosophical definition of lying is to utter deliberate falsehoods in a context that ordinarily requires truth-telling. The context of the game Diplomacy is not one that ordinarily requires truth-telling. Deception is built into the fabric of the game: it’s part of what makes it fun. And since there are no serious long-term consequences of this deception, it’s once again hard to see where the immorality is. So, for me, the kinds of games that Yorke is quick to rule out would not be ruled out in Suits’s utopia.

I have similar issues with Yorke’s characterisation of boring games. I might concede that soluble games and games of pure chance and pure skill would eventually become boring, but that doesn’t mean that they couldn’t be entertaining for a period of time (e.g. while people are figuring out the solution or developing the skill) and it doesn’t mean that we couldn’t create a neverending series of such games to stave off the boredom. In other words, Suits’s injunction against boredom need not be interpreted as an injunction against individual games that might eventually be boring, but as an injunction against the total set of games that utopians might play. Furthermore, just because a game might be soluble does not mean that humans will be able to solve it using their cognitive capacities. Machines might be able to solve many games that humans currently cannot, but that does not mean that the machine-solutions will be epistemically accessible to humans. A world of post-instrumental technological abundance is not necessarily one in which humans acquire superior cognitive abilities…or is it? That’s where we come to Yorke’s second argument.

3. The Unintelligibility of a Post-Instrumentalist Society

Yorke has another strategy for defending premise (2). This one takes aim at the very idea of a post-instrumentalist society. He argues that there is a significant ‘cultural gap’ our society and the one imagined by Suits. This post-instrumentalist society is consequently unintelligible to us from our current standpoint. One way in which you can test this is to look to Suits’s descriptions of that society. Yorke argues that they are not truly post-instrumentalist.

Recall, the basic definition of a post-instrumentalist society: it is one in which the need for all instrumental activities has been eliminated. But when you read what Suits has written, it’s clear that not all instrumental activities have been eliminated. He still talks about the need to eat and to stave off boredom. These are instrumental goals that need to be addressed by different activities. Furthermore, since human beings are biological creatures they will always have such instrumental needs. In fact, human beings are, in many ways, the quintessential instrumentalist creatures: we are distinguished from all other species by the flexibility of our means-end reasoning:

Scott Kretchmar argues from an anthropological standpoint that human beings have always been a need-driven species, and that this helps to explain how we have become the problem-solving and problem-seeking animals we are today [reference omitted]. We needn’t completely buy into a Darwinist line to appreciate Kretchmar’s perfectly reasonable observations about our species’ unique relation to obstacles, which stands as one of our defining characteristics.

(Yorke, 16)

The point here is that a truly post-instrumentalist society would be one in which humans are radically different from what they currently are, i.e. one in which we have achieved some ‘posthuman’ state of existence. But since we have not currently achieved this state of existence, the idea is clearly be unintelligible to creatures like us. To state this in argumentative form:

- (6) Suits’s utopia of games rests on the idea of a truly post-instrumentalist society.

- (7) A truly post-instrumentalist society would only be intelligible to posthumans.

- (8) We are not posthumans.

- (2) Therefore, Suits’s utopia of games is not intelligible.

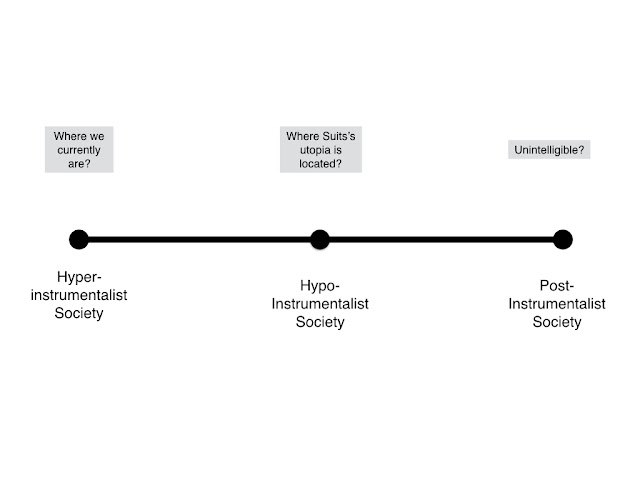

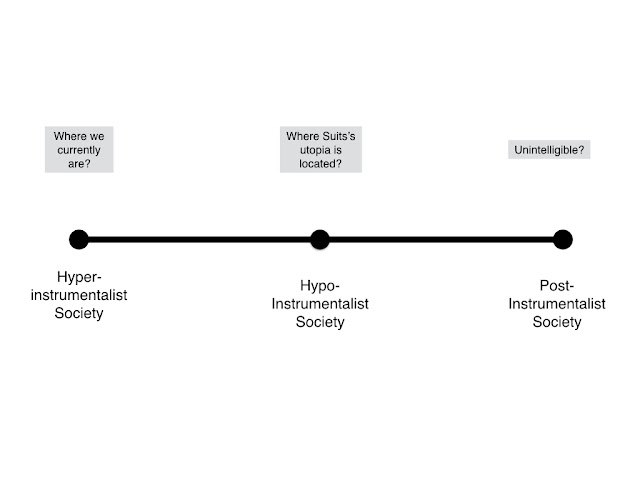

You can resist this argument. Premise (6) is particularly vulnerable to critique. As Yorke himself points out, since the idea of a truly post-instrumentalist society is so difficult to imagine, it’s probably not what Suits’s was trying to describe or defend. We can think of the instrumentalist nature of a society as something that exists in degrees. We currently live in what we might call a ‘hyper-instrumentalist’ society — i.e. one in which instrumentalist activity is rampant and central to our existence. This represents one extreme end of the spectrum of possible societies. At the other end is the completely ‘post-instrumentalist’ society — i.e. the one in which the need for instrumentalist activity has been completely eliminated. Between these two extremes, possibly closer to the post-instrumentalist end, lies the ‘hypo-instrumentalist’ society — i.e. the one in which many, but not all, instrumentalist activities have been eliminated.

It’s likely that Suits’s utopia of games is intended to exist in a hypo-instrumentalist society, not a truly post-instrumentalist society. In particular, it is supposed to exist in a society in which any need for physical labour in order to secure the basic goods of life — food, shelter, material consumables etc. — has been eliminated by technology. Other instrumental needs — e.g. the need for status, friendship, entertainment etc — may well remain.

Moving Suits’s utopia away from the extreme of post-instrumentalism could make his world more relatable to our own, but it all depends on how far away it is. Yorke seems to think that Suits’s imagined world of plenitude is so ‘irreducibly foreign’ from our world of scarcity that even the hypo-instrumentalist society is unintelligible to us:

I post that utopian hypo-instrumentality, and the alien values and culture which must of necessity accompany such a state of being, constitute a fatal obstacle to the project of utopian relatability.

(Yorke, 18)

I’m not sure that I agree with this. I don’t think the idea of a post-scarcity society is as unintelligible as Yorke claims. Although there is undoubtedly much poverty and immiseration in a world today, there are some pockets of post-scarcity. In developed economies there is a seeming abundance of material goods, food and energy. It may well be an illusion — and one that is revealed as such in emergency situations — but for all practical, day-to-day purposes it gets pretty close to post-scarcity. Furthermore, there are some groups of people — super-wealthy elites — who probably get pretty close to living a post-scarcity life when it comes to these material goods and basic services. We could look to them for guidance on what a post-scarcity society would look like.

There are however deeper philosophical problems with hypo-instrumentalism and post-scarcity. The main problem is that the human capacity for instrumentalism, and for finding new forms of scarcity, may be infinite. What were once ‘wants’ can quickly turn into ‘needs’ and can be pursued with all the vigour and urgency that entails. So while we may eliminate certain instrumental needs from human life (e.g. the need for food or shelter), I think humans would quickly reallocate their mental resources to other perceived needs (e.g. the need for social status). This new need could then be pursued in a hyper-instrumentalist way, i.e. become the major focal point in society. I could easily imagine this happening in Suits’s utopia of games. So I’m not sure that we can ever achieve hypo-instrumentalism.

That said, I don’t think this makes Suits’s claim that games represent an ideal of existence unintelligible. It might make particular reading or interpretation of that ideal unintelligible, but the basic idea that we would be better off playing games than dedicating our time to securing our basic material well-being, could still be salvageable.