|

| From Tony Webster on Flickr |

Do you remember Moby? When I was younger — and this probably shows my age — he was quite popular. His album Play sold millions of copies around the world and the singles from it were played endlessly on the radio. The album was unusual. It was a fusion of modern day electronica with samples of blues and gospel music, many of them recorded in the 1930s. The two styles were spliced together to create the aural template for the album. Moby made a lot of money from this album and although his subsequent albums did well he never quite scaled the same heights with his later work. The success of Play was not uncontroversial. Some people complained about Moby’s use of those blues and gospel recordings. They were what gave the album its distinctive sound. But what those African-American singers from whom they were taken? How did those recordings come into existence? Did Moby unethically appropriate their culture for his own ends?

Criticisms of cultural appropriation are everywhere nowadays. It seems like nearly every attempt by a cultural outsider to recreate or modify something from another culture is challenged on this ground. Of all the manifestations of identity politics, this is the one I struggle with the most. I am on the record as having previously said that I think there is something problematic about the tendency to ignore or suppress the cultural products of another culture unless they are ‘spoken’ to us by a member of our own. At the very least, it seems counterproductive to intercultural communication. But I also worry that there is a tendency in criticisms of cultural appropriation to assume that cultures are well-defined, ontological units that ought to be hermetically sealed off from one another. I fear that this leaves limited room for the cross-pollination of cultural ideas, and assumes that certain people have an indubitable, and unwarranted, epistemic authority to speak on behalf of an entire culture.

Erich Hatala Matthes’s paper ‘Cultural Appropriation without Cultural Essentialism?’ helps to clarify some of my unease. In this paper, Matthes argues that there is a tension at the heart of criticisms of cultural appropriation. The tension arises from the fact that any criticism of cultural appropriation must assume that there is an essential core to a culture that allows us to clearly distinguish between cultural insiders and cultural outsiders. This is problematic because it leads to cultural essentialism, which results in harms that are very similar to those caused by cultural appropriation. I will try to unpack this tension in what follows. Even though Matthes tries to resolve the tension in his paper, I’m not sure that his solution adequately addresses the problem.

1. What is Cultural Appropriation and Why is it Harmful?

Apart from Matthes, James Young is the philosopher who has probably done the most work on the topic of cultural appropriation, but Young understands the phenomenon in a particular way. For Young, cultural appropriation arises whenever one culture represents, takes or uses cultural items from another culture. When the Earl of Elgin took the marble statues from the Parthenon in Greece, he, as a representative of British culture, was appropriating something from Greek culture. When Elvis adopted the musical stylings of African-American artists, he was engaging in cultural appropriation. It’s easy to think of other examples that fit this motif.

Understood in this way, Young argues that cultural appropriation is not as big a deal as many people think. He makes this argument by considering the harms that might arise from the representation, taking or use of cultural items. He divides these harms up into different types. One harm that might arise is the harm of misrepresentation, i.e. the inaccurate or misleading portrayal of a culture by outsiders. Another is that of assimilation, i.e. the taking over of one culture by another. And yet another is the loss of economic opportunity, i.e. the profiting by the outsiders at the expense of the cultural insiders. Young then argues that these harms are less common than usually assumed, not as harmful as assumed, and, furthermore, not distinctive to the act of cultural appropriation. In other words, misrepresentation, assimilation and loss of economic opportunity are the real problems here, not cultural appropriation per se. Those harms can arise irrespective of whether there is an act of appropriation.

Matthes finds Young’s analysis lacking. He doesn’t think it captures what critics of cultural appropriation are really concerned about. If you look at the writings of people who criticise cultural appropriation you find that they are not just concerned about things like misrepresentation, loss of economic opportunity and assimilation — though they do sometimes care about those things. There is something more going on. They are concerned about structural injustices and power imbalances. This is one reason why criticisms of cultural appropriation tend to be asymmetrical in nature. It’s usually only when members of dominant cultures appropriate something from minority cultures that hackles are raised. And they are raised precisely because it is felt that cultural appropriation contributes to and consolidates those power imbalances.

Matthes goes further than this. He argues that the harm of cultural appropriation is best understood in terms of cognate harms like silencing and epistemic injustice. These are concepts that have emerged from the ethics of speech and communication in recent years. Epistemic injustice can take different forms but at its core it arises when an audience systematically fails to uptake (or hear) what is being said to them by particular speakers. For example, men who fail to take seriously women’s testimony about experiences of sexual harassment are perpetuating a form of epistemic injustice. They both ignore or downplay what it being said to them by women and encourage women to self-censor because they know they won’t be taken seriously. Matthes argues that the harm of cultural appropriation is in the same general ballpark. It contributes to the marginalisation of minority cultures. If their ideas and cultural products are only taken seriously when represented, taken or used by a member of a dominant culture, then they are denied a social ‘voice’. This is true even if the member of the dominant culture means well and accurately represents the minority culture: sometimes, in order to redress the imbalance of power, members of the dominant culture should remain silent.

This might be a more illuminating take on the harm of cultural appropriation, but it does mean that that harm is reducible to the harm of marginalisation and social oppression. Matthes, however, doesn’t see this as a problem since cultural appropriation is a specific mechanism of marginalisation and oppression. It’s worth understanding the mechanisms of harm as well as harms themselves. The means matter as well as the ends.

2. The Paradox of Cultural Essentialism

But there’s a problem with this account of cultural appropriation. As Matthes notes, if we grant that cultural appropriation is harmful then it seems to follow that we should identify it when it occurs and try to resolve it in some way. Currently popular methods of doing this including ‘calling out’ people who engage in cultural appropriation and subjecting them to criticism or shame or other condemnation. Other responses are possible too, including perhaps compensation for profiting from the culture of another, changes in representational quotas, or changes to the norms of social discourse and debate that give people from minority cultures more voice. But no matter what the response is, it seems like we need to be able to accurately identify instances of cultural appropriation and explain why they warrant that label.

And this is where the problem arises. To accurately identify instances of cultural appropriation we must reliably distinguish between cultural insiders and outsiders. After all, the representation, use and taking of the cultural products of Culture A is only ever a problem if it is done by someone from another culture, say Culture B. The problem with this is that it assumes that there are essential properties that are reliably shared by all cultural insiders that allow us to make these distinctions in an unproblematic way. So, for example, Moby’s use of African-American gospel and blues recordings is only a harmful instance of cultural appropriation if we can say with some certainty that Moby is not a member of the African-American community. Now, you might argue that this is obviously true: Moby clearly is not African-American. But other cases are less clear-cut. Is Barack Obama African-American? Well, it’s complicated. His mother was white and although his father was from Kenya (which is indeed in Africa) that means he is not a direct descendant of the former slave communities that were forcibly taken from Africa to America. So perhaps Obama is an outsider to African-American culture as it is commonly understood and so cannot be a spokesperson for the experiences of that community. And this is just the example of race-based cultures. Things get even more complicated when we look at ethnic groups and religious identity groups.

For any complex assemblage of persons, traditions and histories, it’s highly unlikely that there will be some core or essence that is reliably shared by all members of the group. So when you use a criterion (or set of criteria) for drawing the line between one culture and another, you risk arbitrarily and unjustly excluding some people from the community. What’s more, you also risk giving people within the arbitrarily defined community additional epistemic authority that they may not warrant. Suddenly they have both the power (and the burden) of speaking on behalf of an entire community, some of whom may not share all of their experiences and beliefs. And this can end up marginalising and silencing people who do not fit with the arbitrarily imposed group definition. This is the problem of cultural essentialism.

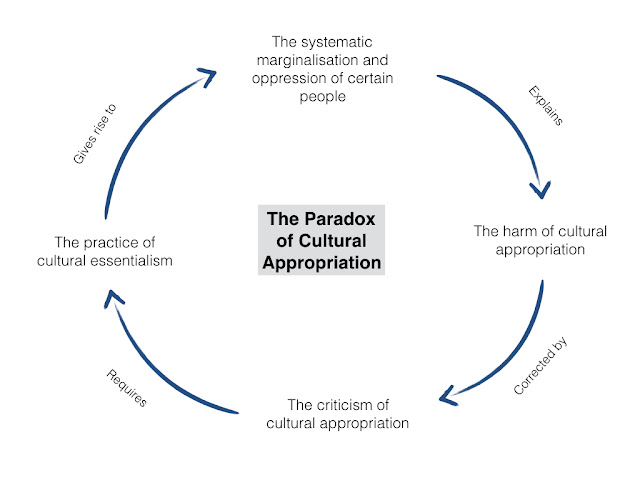

This looks like a paradox. It seems that in our effort to address the problem of social marginalisation and oppression we risk engaging in a practice that does the very same thing, albeit maybe to a different group of people (those who fall between the cracks of our defined cultural enclaves). To set out the paradox in more formal terms:

- (1) Cultural appropriation is harmful because it contributes to the social marginalisation and oppression of certain groups of people.

- (2) In order to police and respond to harmful instances of cultural appropriation you have to engage in cultural essentialism.

- (3) Cultural essentialism is harmful because it contributes to the social marginalisation and oppression of certain groups of people.

- (4) Therefore, in order to properly police the harm of cultural appropriation you have to commit the harm of cultural essentialism, which are similar kinds of harms.

Now this isn’t is pure paradox, as Matthes notes. The fact that it may be different groups of people that are being harmed by the respective practices saves cultural appropriation from complete contradiction. But it has the general whiff of paradox: it seems that instead of solving the problem we set out to solve we redistribute it instead. That can’t be what we are aiming for, can it?

3. Resolving the Paradox of Cultural Appropriation

There are several responses to this. Most of them take aim at premise (2) of the argument, though some also take issue with the claim that essentialism is harmful. Matthes investigates five of these responses, finding them all lacking. He then develops his own. I’ll consider them all in turn here.

The first response argues that we don’t need to be essentialists in order to police and respond to cultural appropriation. We can, instead, adopt a ‘family resemblance’ approach to cultural membership. In other words, members of cultures may not share one particular property, but there will be overlapping resemblances between them — just as the members of a family may not share any one distinguishing feature but nevertheless be similar enough to know that they all belong to the same family. Matthes finds this lacking because he thinks it doesn’t solve the problem of essentialism. You still have to agree on a list of overlapping properties that determine cultural membership and someone still needs to decide who belongs and who does not.

The second response argues that we don’t need to be essentialists because we can just leave it individuals to decide whether they are members or not. In other words, we can adopt a ‘self-identification’ rule for cultural membership. We already do this for some identity groupings. But it is obviously problematic insofar as it dissolves the problem of cultural appropriation. The distinction between a cultural insider and outsider becomes meaningless if people can just self-identify as belonging to a group. It’s also pretty clear that this wouldn’t work in practice since cultural insiders often resist the self-identification rule of membership when perceived outsiders claim to be part of their culture.

The third response argues that we can adopt different methods for determining cultural membership depending on the interests that are at stake. This comes from the work of Suzy Killmister who has argued for it in other contexts. The idea, as best I can tell, is that we should consider the interests that different people have in avoiding certain harmful outcome (such as the harm of systematic oppression or silencing) and then adopt a method for determining group membership that tracks their interests. The problem with this is that we can only tell if a person has an interest in avoiding the harm of cultural appropriation if we already know that they are a member of a particular group. So this puts the cart before the horse.

The fourth response argues that we can tolerate some essentialism on strategic grounds. The idea here is that there is some limited value to cultural essentialism if it allows us to stamp out the most egregious cases of cultural appropriation. We are not exactly shy or reluctant about assigning people to different cultural groups. We do this all the time and it is what leads to the harm of cultural appropriation. Why not just accept this for what it is and use it to address the problems raised by appropriation? And since different people are going to be affected by appropriation vis-a-vis essentialism this might also be justified on utilitarian or consequentialist grounds. The problem with this is that the strategic value of essentialism presupposes, to at least some extent, the descriptive accuracy of the distinctions we draw between different groups. So it’s not clear that the argument is all that strong unless we can be confident about those distinctions.

The fifth response argues that we can use lineages instead of essential properties to determine cultural membership. The idea here is that cultures and individual members of cultures are defined by their histories and origins. If you share the right lineage or historical experiences, then you are a cultural insider; if not, you are an outsider. Again, this can be problematic if those who don’t share the right lineage or set of experiences are automatically excluded (Barack Obama is again a potential example). As Matthes puts it, sharing a lineage might be a sufficient condition for cultural membership, but it would be wrong to assume that it is a necessary condition.

Having found each of these responses lacking, Matthes argues for his own. It’s a little bit like the strategic response outlined above, but with one critical difference. Matthes thinks we should accept the cultural boundaries that are already there in our social life, but that we should avoid policing specific instances of cultural appropriation in the way that we currently do. In other words, he thinks that the problem with strategic essentialism is that it can be used as a bully tactic to police and shame individuals for engaging in specific acts of appropriation. But we shouldn’t be doing this if cultural appropriation is a systematic harm. After all, if it is a systematic harm it is not something that any one individual is really responsible for, even if their behaviour reinforces it. This means we should, according to Matthes, focus less on blaming the appropriator and more on addressing the negative effects of the appropriation:

Cultural appropriation is a way that an individual can act harmfully in conjunction with systematic inequality, but we do not need to identify the agent or attribute responsibility to them in individual cases in order to understand the nature of such harms in general. Especially since harms that are a function of artistic expression and representation are ones we may be particularly hesitant about regulating, we may be better served by focusing on ameliorating the harmful effects, which is itself part of the task of combatting the ultimate harmful cause: namely, working to eliminate systematic social marginalization

(Matthes 2016)

I think Matthes is right that we should not assign individual blame for instances of appropriation, given the problem of essentialism. But I’m not sure if this is a practicable solution to the problem. For one thing, I imagine that people are going to be very wedded to the idea of assigning individual blame in cases of alleged appropriation. The desire to punish and blame is deeply-seated in our psychologies. We want a scapegoat: someone we can criticise. When a movie studio decides to cast a white actor in a role that should (in some appropriate sense of the word should) have gone to someone from a minority group, people want to blame the actor or the studio. They want to call them out for perpetuating the systematic marginalisation of certain groups. It’s part of what makes the practice feel motivating and worthwhile. Furthermore, it’s not clear to me how we could address the effects of this marginalisation without doing something that is going to seem punitive to the appropriator. In the case of the actor, the obvious remedy is to take the part away from them and give it to an actor from the relevant community; in the case of another kinds of appropriation, the obvious solution will be to boycott, ignore, criticise or redistribute the gains of the appropriation. It’s hard to imagine that this wouldn’t be taken personally or be felt personally. So it may be that it is simply impossible to police appropriation without some individual responsibility and punishment. Otherwise why bother? Why not just focus on correcting for systematic marginalisation more generally (i.e. without trying to identify specific cases of appropriation)?

In fairness, Matthes recognises some of these concerns and is, in the end, equivocal about his solution. Nevertheless, he doesn’t talk about one of the major concerns I have about appropriation and essentialism. That’s fine, of course: I don’t expect everything to speak to my concerns. But I want to conclude by talking a bit this concern. It has to do with the tendency for criticisms of appropriation, and the concomitant identification of cultural insiders and outsiders, to ossify cultures themselves and assign people to predefined cultural enclaves (this is something I touched on in my post about the open society and identity politics). One thing I have noticed in recent discussions of cultural appropriation is that they often carry with them (a) the assumption that an outsider can never understand or use a cultural product themselves and (b) that cultures and their products are beyond criticism and improvement. This seems counterproductive to me. If anything it encourages, rather than prevents, marginalisation and ghettoisation. It also discourages innovation and progress. I can’t imagine anything more ahistorical and culturally insensitive than that.

This brings me back to the point I made at the end of my previous post on identity politics. When it comes to something like the criticism of cultural appropriation, it’s all a matter of ‘dial adjustment’: there’s a way of doing it that is valuable, that fosters intercultural dialogue and enables cooperation, diversity and innovation; and there’s a way of doing it that isn’t, that encourages conflict and stagnation, and celebrates ignorance. It’s important to get the setting right.