[Note: This is the text of a talk I delivered to the AI and Legal Disruption (AI-LeD) workshop in Copenhagen University on the 28th September 2018. As I said at the time, it is intended to be a ‘thinkpiece’ as opposed to a well-developed argument or manifesto. It’s an idea that I’ve been toying with for awhile but have not put it down on paper before. This is my first attempt. It makes a certain amount of sense to me and I find it useful, but I’m intrigued to see whether others do as well. I got some great feedback on the ideas in the paper at the AI-LeD workshop. I have not incorporated those into this text, but will do so in future iterations of the framework I set out below.]

What effect will artificial intelligence have on our moral and legal order? There are a number of different ‘levels’ at which you can think about this question.

(1) Granular Level: You can focus on specific problems that arise from specific uses of AI: responsibility gaps with self-driving cars; opacity in credit scoring systems; bias in sentencing algorithms and so on. The use of AI in each of these domains has a potentially ‘disruptive’ effect and it is important to think about the challenges and opportunities that arise. We may need to adopt new legal norms to address these particular problems.

(2) Existential Level: You can focus on grand, futuristic challenges posed by the advent of smarter-than-human AI. Will we all be turned into paperclips? Will we fuse with machines and realise the singularitarian dreams of Ray Kurzweil? These are significant questions and they encourage us to reflect on our deep future and place within the cosmos. Regulatory systems may be needed to manage the risks that arise at this existential level (though they may also be futile).

(3) Constitutional Level: You can focus on how advances in AI might change our foundational legal-normative order. Constitutions enshrine our basic rights and values, and develop political structures that protect and manage these foundational values. AI could lead to a re-prioritising or re-structuring of our attitude to basic rights and values and this could require a new constitutional order for the future. What might that look like?

Lots of work has been done at the granular and existential levels. In this paper, I want to make the case for more work to be done at the constitutional level. I think this is the important one and the one that has been neglected to date. I’ll make this case in three main phases. First, I’ll explain in more detail what I mean by the ‘constitutional level’ and what I mean by ‘artificial intelligence’. Second, I’ll explain why I think AI could have disruptive effects at the constitutional level. Third, I’ll map out my own vision of our constitutional future. I’ll identify three ‘ideal type’ constitutions, each associated with a different kind of intelligence, and argue that the constitutions of the future will emerge from our exploration of the possibility space established by these ideal types. I’ll conclude by considering where I think things should go from here.

1. What is the constitutional level of analysis?

Constitutions do several different things and they take different forms. Some might argue that this variability in constitutional form and effect makes it impossible to talk about the ‘constitutional level’ of analysis in a unitary way. I disagree. I think that there is a ‘core’ or ‘essence’ to the idea of a constitution that makes it useful to do so.

Constitutions do two main things. First, they enshrine and protect fundamental values. What values does a particular country, state, legal order hold dear? In liberal democratic orders, these values usually relate to individual rights and democratic governance (e.g. right to life, right to property, freedom of speech and association, freedom from unwarranted search and seizure, right to a fair trial, right to vote etc.). In other orders, different values can be enshrined. For example, although this is less and less true, the Irish constitution had a distinctively ‘Catholic’ flavour to its fundamental values when originally passed, recognising the ‘special place’ of the Catholic Church in the original text, banning divorce and (later) abortion, outlawing blasphemy, and placing special emphasis on the ‘Family’ and its role in society. It still had many liberal democratic rights, of course, which also illustrates how constitutions can blend together different value systems.

Second, constitutions establish institutions of governance. They set out the general form and overall function of the state. Who will rule? Who will pass the laws? Who will protect the rule of law? Who has the right to create and enforce new policies? And so on. These institutions of governance will typically be required to protect the fundamental values that are enshrined in the constitution, but they will also have the capacity for dynamic adaptation — to ensure that the constitutional order can grow and respond to new societal challenges. In this regard, one of the crucial things that constitutions do, as has been argued by Adrian Vermeule in his book The Constitution of Risk, is that they help to manage ‘political risk’, i.e. the risk of bad governance. If well designed, a constitution should minimise the chances of a particular government or ruler destroying the value structure of the constitutional system. That, of course, is easier said than done. Ultimately, it’s power and the way in which it is exercised that determines this. Constitutions enable power as well as limit it, and can, for that reason, be abused by charismatic leaders.

The constitutional level of analysis, then, is the level of analysis that concerns itself with: (i) the foundational values of a particular legal order and (ii) the institutions of governance within that order. It is distinct from the granular level of analysis because it deals with general, meta-level concerns about social order and institutions of governance. The granular level deals with particular domains of activity and what happens within them. HLA Hart’s distinction between primary and secondary legal rules might be a useful guide here, for people who know it. It is also distinct from the existential level of analysis (at least as I understand it) because that deals, almost exclusively, with extinction style threats to humanity as a whole. That said, there is more affinity between the constitutional level of analysis and some of the issues raised in the ‘existential risk’ literature around AI. So what I am arguing in this paper could be taken as a plea to reframe or recategorise parts of that discussion.

It is my contention that AI could have significant and under-appreciated effects at the constitutional level. To make the case for this, it would help if I gave a clearer sense of what I mean by ‘artificial intelligence’. I don’t have anything remarkable to say about this. I follow Russell and Norvig in defining AI in terms of goal-directed, problem-solving behaviour. In other words, an AI is any program or system that acts so as to achieve some goal state. The actions taken will usually involve some flexibility and, dare I say it, ‘creativity’, insofar as there often isn’t a single best pathway to the goal in all contexts. The system would also, ideally, be able to learn and adapt in order to count as an AI (though I don’t necessarily insist on this as I favour a broad definition of AI). AI, so defined, can come in specialised, narrow forms, i.e. it may only be able to solve one particular set of problems in a constrained set of environments. These are the forms that most contemporary AI systems take. The hope of many designers is that these systems will eventually take more generalised forms and be able to solve problems across a number of domains. There are some impressive developments on this front, particularly from companies like DeepMind that have developed an AI that learns how to solve problems in different contexts without any help from its human programmers. But, still, the developments are at an early stage.

It is generally agreed that we are now living through some kind of revolution in AI, with rapid progress occurring on multiple fronts particularly in image recognition, natural language processing, predictive analytics, and robotics. Most of these developments are made possible through a combination of big data and machine learning. Some people are sceptical as to whether the current progress is sustainable. AI has gone through at least two major ‘winters’ in the past when there seemed to be little improvement in the technology. Could we be on the cusp of another winter? I have no particular view on this. The only thing that matters from my perspective is that (a) the developments that have taken place in the past decade or so will continue to filter out and find new use cases and (b) there are likely to be future advances in this technology, even if they occurs in fits and starts.

2. The Relationship Between AI and Constitutional Order

So what kinds of effects could AI have at the constitutional level? Obviously enough, it could affect either the institutions of governance that we use to allocate and exercise power, or it could affect the foundational values that we seek to enshrine and protect. Both are critical and important, but I’m going to focus primarily on the second.

The reason for this is that there has already been a considerable amount of discussion about the first type of effect, even though it is not always expressed in these terms. The burgeoning literature on algorithmic governance — to which I have been a minor contributor — is testament to this. Much of that literature is concerned with particular applications of predictive analytics and data-mining in bureaucratic and institutional governance. For example, in the allocation of welfare payments or in sentencing and release decisions in the criminal justice system. As such it can seem to be concerned with the granular level. But there have been some contributions to the literature that concern themselves more generally with the nature of algorithmic power and how different algorithmic governance tools can be knitted together to create an overarching governance structure for society (what I have called an ‘algocracy’, following the work of the sociologist A.Aneesh). There is also growing appreciation for the fact that the combination of these tools can subvert (or reinforce) our ideologically preferred mode of governance. This conversation is perhaps most advanced among blockchain enthusiasts, several of whom dream of creating ‘distributed autonomous organisations’ that function as ‘AI Leviathans’ for enforcing a preferred (usually libertarian) system of governance.

These discussions of algorithmic governance typically assume that our foundational values remain fixed and non-negotiable. AI governance tools are perceived either as threats to these values or ways in which to protect them. What I think is ignored, or at least not fully appreciated, is the way in which AI could alter our foundational values. So that’s where I want to focus my analysis for the remainder of this paper. I accept that there may be different ways of going about this analytical task, but I’m going to adopt a particular approach that I think is both useful and illuminating. I don’t expect it to be the last word on the topic; but I do think it is a starting point.

My approach works from two observations. The first is that values change. This might strike some of you as terribly banal, but it is important. The values that someone like me (an educated, relatively prosperous, male living in a liberal democratic state) holds dear are historically contingent. They have been handed down to me through centuries of philosophical thought, political change, and economic development. I might think they are the best values to have; and I might think that I can defend this view through rational argument; but I still have to accept that they are not the only possible values that a person could have. A cursory look at other cultures and at human history makes this obvious. Indeed, even within the liberal democratic states in which I feel most comfortable there are important differences in how societies prioritise and emphasise values. It’s a cliche, but it does seem fair to say, that the US seems to value economic freedom and individual prosperity more than many European states, which place a greater emphasis on solidarity and equality. So there are many different possible ways of structuring our approach to foundational values, even if we agree on what they are.

Owen Flanagan’s book The Geography of Morality: Varieties of Moral Possibility sets out what I believe is the best way to think about this issue. Following the work of moral psychologists like Jonathan Haidt, Flanagan argues that there is a common, evolved ‘root’ to human value systems. This root centres on different moral dimensions like care/harm, fairness/reciprocity, loyalty, authority/respect, and purity/sanctity (this is just Haidt’s theory; Flanagan’s theory is a bit more complex as it tries to fuse Haidt’s theory with non-Western approaches). We can turn the dial up or down on these different dimensions, resulting in many possible combinations. So from this root, we can ‘grow’ many different value systems, some of which can seem radically opposed to one another, but all of which trace their origins back to a common root. The value systems that do develop can ‘collide’ with one another, and they can grow and develop themselves. This can lead to some values falling out of favour and being replaced by others, or to values moving up and down a hierarchy. Again, to use the example of my home country of Ireland, I think we have seen over the past 20 years or so a noticeable falling out of favour of traditional Catholic values, particularly those associated with sexual morality and the family. These have been replaced by more liberal values, which were always present to some extent, but are now in the ascendancy. Sometimes these changes in values can be gradual and peaceful. Other times they can be more abrupt and violent. There can be moral revolutions, moral colonisations or moral cross-fertilisations. Acknowledging the fact that values change does not mean that we have to become crude ‘anything goes’ moral relativists; it just means that we have to acknowledge historical reality and to, perhaps, accept that the moral ‘possibility space’ is wider than we initially thought. If it helps, you can distinguish between factual/descriptive values and actual moral values if you are worried about being overly relativistic.

The second observation is that technology is one of the things that can affect how values change. Again, this is hardly a revelatory statement. It’s what one finds in Marx and many other sociologists. The material base of society can affect its superstructure of values. The relationship does not have to be unidirectional or linear. The claim is not that values have no impact on technology. Far from it. There is a complex feedback loop between the two. Nevertheless, change in technology, broadly understood, can and will affect the kinds of values we hold dear.

There are many theories that try to examine how this happens. My own favourite (which seems to be reasonably well-evidenced) is the one developed by Iain Morris in his book Foragers, Farmers and Fossil Fuels. In that book, Morris argues that the technology of energy capture used by different societies affects their value systems. In foraging societies, the technology of energy capture is extremely basic: they rely on human muscle and brain power to extract energy from an environment that is largely beyond their control. Humans form small bands that move about from place to place. Some people within these bands (usually women) specialise in foraging (i.e. collecting nuts and fruits) and others (usually men) specialise in hunting animals. Foraging societies tend to be quite egalitarian. They have a limited and somewhat precarious capacity to extract food and other resources from their environments and so they usually share when the going is good. They are also tolerant of using some violence to solve social disputes and to compete with rival groups for territory and resources. They display some gender inequality in social roles, but they tend to be less restrictive of female sexuality than farming societies. Consequently, they can be said to value inter-group loyalty, (relative) social equality, and bravery in combat. Farming societies are quite different. They capture significantly more energy than foraging societies by controlling their environments, by intervening in the evolutionary development of plants and animals, and by fencing off land and dividing it up into estates that can be handed down over the generations. Prior to mechanisation, farming societies relied heavily on manual labour (often slavery) to be effective. This led to considerable social stratification and wealth inequality, but less overall violence. Farming societies couldn’t survive if people used violence to settle disputes. There was more focus on orderly dispute resolution, though the institutions of governance could be quite violent. Furthermore, there was much greater gender inequality in farming societies as women took on specific roles in the home and as the desire to transfer property through family lines placed on emphasis on female sexual purity. This affected their foundational values. Finally, fossil fuel societies capture enormous amounts of energy through the combustion and exploitation of fossil fuels (and later nuclear and renewable energy sources). This enabled greater social complexity, urbanisation, mechanisation, electrification and digitisation. It became possible to sustain very large populations in relatively small spaces, and to facilitate more specialisation and mobility in society. As a result, fossil fuel societies tend to be more egalitarian than farming societies, particularly when it comes to political and gender equality, though less so when it comes to wealth inequality. They also tend to be very intolerant of violence, particularly within a defined group/state.

This is just a very quick sketch of Morris’s theory. I’m not elaborating the mechanisms of value change that he talks about in his book. I use it for illustrative purposes only; to show how one kind of technological change (energy capture) might affect a society’s value structure. Morris is clear in his work that the boundaries between the different kinds of society are not clearcut. Modern fossil fuel societies often carry remnants of the value structure of their farming ancestry (and the shift from farming isn’t complete in many places). Furthermore, Morris speculates that advances in information technology could have a dramatic impact on our societal values over the next 100 years or so. This is something that Yuval Noah Harari talks about in his work too, though he has the annoying habit of calling value systems ‘religions’. In Homo Deus he talks about how new technologically influenced religions of ‘transhumanism’ of ‘dataism’ are starting to impact on our foundational values. Both of these ‘religions’ have some connection to developments in AI. We already have some tangible illustrations of the changes that may be underway. The value of privacy, despite the best efforts of activists and lawmakers, is arguably on the decline. When faced with a choice, people seem very willing to submit themselves to mass digital surveillance in order to avail of free and convenient digital services. I suspect that it continues to be true despite the introduction of the new GDPR in Europe. Certainly, I have found myself willing to consent to digital surveillance in its aftermath for the efficiency of digital media. It is this kind of technologically-influenced change that I am interested in here and although I am inspired by the work of Morris and (to a lesser extent) Harari I want to present my own model for thinking about it.

3. The Intelligence Triangle and the Constitutions of the Future

My model is built from two key ideas. The first is the notion of an ideal type constitution. Human society is complex. We frequently use simplifying labels to make sense of it all. We assign people to general identity groups (Irish, English, Catholic, Muslim, Black, White etc) even though we know that the experiences of any two individuals plucked from those identity groups are likely to differ. We also classify societies under general labels (Capitalist, Democratic, Monarchical, Socialist etc) even though we know that they have their individual quirks and variations. Max Weber argued that we need to make use of ‘ideal types’ in social theory in order to bring order to chaos. In doing so, we must be fully cognisant of the fact that the ideal types do not necessarily correspond to social reality.

Morris makes use of ideal types in his analysis of the differences between foraging, farming and fossil fuel societies. He knows that there is probably no actual historical society that corresponds to his model of a foraging society. But that’s not the point of the model. The point is to abstract from the value systems we observe in actual foraging societies and use them to construct a hypothetical, idealised model of a foraging society’s value system. It’s like a Platonic form — a smoothed out, non-material ‘idea’ of something we observe in the real world — but without the Platonic assumption that the form is more real than what we find in the world. I’ll be making use of ideal types in my analysis of how AI can affect the constitutional order.

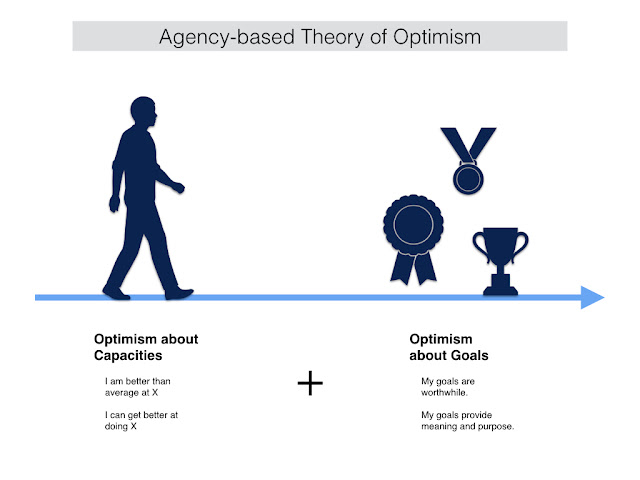

This brings me to the second idea. The key motivation for my model is that one of the main determinants of our foundational values is the form of intelligence that is prioritised in society. Intelligence is the basic resource and capacity of human beings. It’s what makes other forms of technological change possible. For example, the technology of energy capture that features heavily in Morris’s model is itself dependent on how we make use of intelligence. There are three basic forms that intelligence can take: (i) individual, (ii) collective and (iii) artificial. For each kind of intelligence there is a corresponding ideal type constitution, i.e. a system of values that protects, encourages and reinforces that particular mode of intelligence. But since these are ideal types, not actual realities, it makes most sense to think about the kinds of value system we actually see in the world as the product of tradeoffs or compromises between these different modes of intelligence. Much of human history has involved a tradeoff between individual and collective intelligence. It’s only more recently that ‘artificial’ forms of intelligence have been added to the mix. What was once a tug-of-war between the individual and the collective has now become a three-way battle* between the individual, the collective and the artificial. That’s why I think AI has the potential to be so be disruptive of our foundational values: it adds something genuinely new to the mix of intelligences that determines our foundational values.

That’s my model in a nutshell. I appreciate that it requires greater elaboration and defence. Let me start by translating it into a picture. They say a picture is worth a thousand words so hopefully this will help people understand how I think about this issue. Below, I’ve drawn a triangle. Each vertex of the triangle is occupied by one of the ideal types of society that I mentioned: the society that prioritises individual intelligence, the society that prioritises collective intelligence, and the one that prioritises artificial intelligence. Actual societies can be defined by their location within this triangle. For example, a society located midway along the line joining the individual intelligence society to the collective intelligence society would balance the norms and values of both. A society located at the midpoint of the triangle as a whole, would balanced the norms and values of all three. And so on.**

But, of course, the value of this picture depends on what we understand by its contents. What is individual intelligence and what would a society that prioritises individual intelligence look like? These are the most important questions. Let me provide a brief sketch of each type of intelligence and its associated ideal type of society in turn. I need to apologise in advance that these sketches will be crude and incomplete. As I have said before, my goal is not to provide the last word on the topic but rather to present a way of thinking about the issue that might be useful.

Individual Intelligence: This, obviously enough, is the intelligence associated with individual human beings, i.e. their capacity to use mental models and tools to solve problems and achieve goals in the world around them. In its idealised form, individual intelligence is set off from collective and artificial intelligence. In other words, the idealised form of individual intelligence is self-reliant and self-determining. The associated ideal type of constitution will consequently place an emphasis on individual rights, responsibilities and rewards. It will ensure that the individual is protected from interference; that he/she can benefit from the fruits of their labour; that their capacities are developed to their full potential; and that they are responsible for their own fate. In essence, it will be a strongly libertarian constitutional order.

Collective Intelligence: This is associated with groups of human beings, and arises from their ability to coordinate and cooperate in order to solve problems and achieve goals. Examples might include a group of hunters coordinating an attack on a deer or bison, or a group of scientists working in lab trying to develop a medicinal drug. According to the evolutionary anthropologist Joseph Heinrich, this kind of group coordination and cooperation, particularly when it is packaged in easy-to-remember routines and traditions, is the ‘secret’ to humanity’s success. Despite this, the systematic empirical study of collective intelligence — why some groups are more effective at problem solving than others — is a relatively recent development albeit an inquiry that is growing in popularity (see, for example, Geoff Mulgan’s book Big Mind). The idealised form of collective intelligence sees the individual as just a cog in a collective mind. And the associated ideal type of constitution is one that emphasises group solidarity and cohesion, collective benefit, common ownership, and possibly equality of power and wealth (though equality is, arguably, more of an individualistic value and so cohesion might be the overriding value). In essence, it will be a strongly communistic/socialistic constitutional order.

I pause here to repeat the message from earlier: I doubt that any human society has ever come close to instantiating either of these ideal types. I don’t believe that there was some primordial libertarian state of nature in which individual intelligence flourished. On the contrary, I suspect that humans have always been social creatures and that the celebration of individual intelligence came much later on in human development. Nevertheless, I also suspect that there has always been a compromise and back-and-forth between the two poles.

Artificial Intelligence: This is obviously the kind of intelligence associated with computer-programmed machines. It mixes and copies elements from individual and collective intelligence (since humans did create it), but it is also based on some of its own tricks. The important thing is that it is non-human in nature. It functions in forms and at speeds that are distinct from us. It is used initially as a tool (or set of tools) for human benefit: a way of lightening or sharing our cognitive burden. It may, however, take on a life of its own and will perhaps one day pursue agendas and purposes that are not conducive to our well-being. The idealised form of AI is one that is independent from human intelligence, i.e. does not depend on human intelligence to assist in its problem solving abilities. The associated ideal type of constitution is, consequently, one in which human intelligence is devalued; in which machines do all the work; and in which we are treated as their moral patients (beneficiaries of their successes). Think about the future of automated leisure and idleness that is depicted in a movie like Wall:E or something similar. Instead of focusing on individual self-reliance and group cohesion, the artificially intelligent constitution will be one that prioritises pleasure, recreation, game-playing, idleness, and machine-mediated abundance (of material resources and phenomenological experiences).

Or, at least, that is how I envision it. I admit that my sketch of this ideal type of constitution is deeply anthropocentric: it assumes that humans will still be the primary moral subjects and beneficiaries of the artificially intelligent constitutional order. You could challenge this and argue that a truly artificially intelligent constitutional order would be one in which machines as the primary moral subjects. I’m not going to go there in this paper, though I’m more than happy to consider it. I’m sticking with the idea of humans being the primary moral subjects because I think that is more technically feasible, at least in the short to medium term. I also think that this idea gels well with the model I’ve developed. It paints an interesting picture of the arc of human history: Human society once thrived on a combination of individual and collective intelligence. Using this combination of intelligences we built a modern, industrially complex society. Eventually the combination of these intelligences allowed us to create a technology that rendered our intelligence obsolescent and managed our social order on our behalf. Ironically, this changed how we prioritised certain fundamental values.

4. Planning for the Constitutions of the Future

I know there are problems with the model I’ve developed. It’s overly simplistic; it assumes that there is only one determinant of fundamental values; it seems to ignore moral issues that currently animate our political and social lives (e.g. identity politics). Still, I find myself attracted to it. I think it is important to think about the ‘constitutional’ impact of AI, and to have a model that appreciates the contingency and changeability of the foundational values that make up our present constitutional order. And I think this model captures something of the truth, whilst also providing a starting point from which a more complex sketch of the ‘constitutions of the future’ can be developed. The constitutional orders that we currently live inside do not represent the ‘end of history’. They can and will change. The way in which we leverage the different forms of intelligence will have a big impact on this. Just as we nowadays clash with rival value systems from different cultures and ethnic groups; so too will we soon clash the value systems from the future. The ‘triangular’ model I’ve developed defines the (or rather ‘a’) ‘possibility space’ in which this conflict takes place.

I want to close by suggesting some ways in which this model could be (and, if it has any merit, should be) developed:

- A more detailed sketch of the foundational values associated with the different ideal types should be provided.

- The link between the identified foundational values and different mechanisms of governance should be developed. Some of the links are obvious enough already (e.g. a constitutional order based on individual intelligence will require some meaningful individual involvement in social governance; one based on collective intelligence will require mechanisms for collective cooperation and coordination and so on), but there are probably unappreciated links that need to be explored, particularly with the AI constitution.

- An understanding of how other technological developments might fit into this ‘triangular’ model is needed. I already have some thoughts on this front. I think that there are some technologies (e.g. technologies of human enhancement) that push us towards an idealised form of the individual intelligence constitution, and others (e.g. network technologies and some ‘cyborg’ technologies) that push us towards an idealised form of the collective intelligence constitution. But, again, more work needs to be done on this.

- A normative defence of the different extremes, as well as the importance of balancing between the extremes, is needed so that we have some sense of what is at stake as we navigate through the possibility space. Obviously, there is much relevant work already done on this so, to some extent, it’s just a question of plugging that into the model, but there is probably new work to be done too.

- Finally, a methodology for fruitfully exploring the possibility space needs to be developed. So much of the work done on futurism and AI tends to be the product of individual (occasionally co-authored) speculation. Some of this is very provocative and illuminating, but surely we can hope for something more? I appreciate the irony of this but I think we should see how ‘collective intelligence’ methods could be used to enable interdisciplinary groups to collaborate on this topic. Perhaps we could have a series of ‘constitutional conventions’ in which such groups actually draft and debate the possible constitutions of the future?

* This term may not be the best. It’s probably too emotive and conflictual. If you prefer, you could substitute in ‘conversation’ or ‘negotiation’.

** This ‘triangular’ graphing of ideal types is not unique to me. Morris uses a similar diagram in his discussion of farming societies, pointing out that his model of a farming society is, in fact, an abstraction from three other types.