“It is better to burn out than to fade away.” These are the lyrics from Neil Young’s song ‘My my, hey hey’ and, famously, featured on Nirvana lead singer, Kurt Cobain’s, suicide note. They capture a common thought: that the trajectory of your life matters. Imagine two lives, both full of equal amounts of pleasure and joy. Despite their seeming equality, you might prefer one over the other simply because its trajectory is more appealing; because it doesn’t end with a long period of stagnation and decline; because it goes out on a high.

Philosophers have long been puzzled about the importance of shape to the well-lived life. There are some — usually hedonists — who think it does not really matter at all. What matters is the aggregate amount of pleasure and pain. If you happen to prefer a life with an upward-sloping trajectory (i.e. one where there is more pleasure toward the end), then this might affect your overall experience of pleasure and pain, and hence might give grounds for favouring the upward-sloping trajectory. But if you have no such preference, then shape doesn’t matter.

There are others who vehemently disagree. They are with Neil Young and Kurt Cobain. They think it is genuinely better, for reasons that have nothing to do with aggregate amounts of pleasure and pain, to have an upward sloping trajectory to your life. They usually justify this on the grounds of narrative arc or relationality. In other words, they favour the upward-sloping trajectory because it tells the better story.

In her paper “What does the shape of a life tell us about its value?”, Christine Vitrano takes on the narrativists and defends the hedonists. I want to look at her argument in what follows. Although I ultimately agree with her, I find myself initially intuitively attracted to the narrativist view. I hope to explain why below.

1. Why the shape of a life might matter

One of the most impressive things about Vitrano’s article is how comprehensive it is in both reviewing and quoting from fans of the narrativist view. By my tally she quotes from at least nine different philosophers who have defended some version of the narrative view. This comprehensive review of the literature clearly proves the point that narrative view is widely favoured.

But why? The main scratching post for Vitrano’s article is a thought experiment she takes from another article by the philosopher Dale Dorsey. The thought experiment asks us to compare two different life trajectories, one real and one fictional:

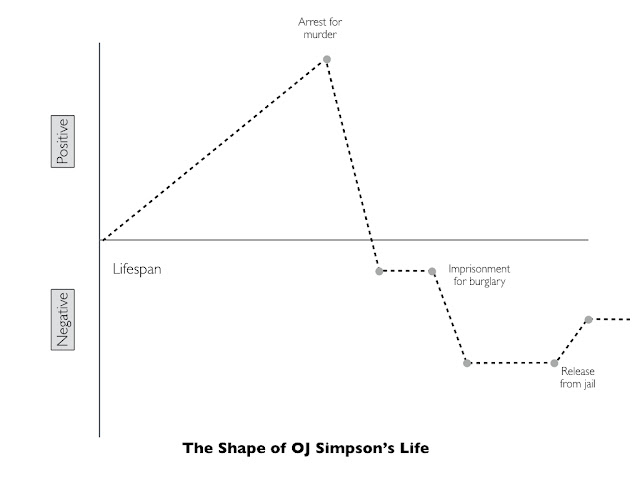

OJ Simpson: OJ Simpson’s life displayed a reasonably solid upward trajectory until he reached his mid-forties. He was a successful football player, actor and sports commentator. Then he was put on trial for murder and, although acquitted, many were convinced of his guilt. His subsequent years have displayed a noticeable downward trajectory. He was arrested and sent to jail for burglary in 2008. He was sentenced to 33 years but was released on parole in 2017. He has largely stayed out of the limelight since then.

JO Nospmis: JO Nospmis started out life on a downward slope. She was involved in gang-related violence and crime from an early age. She was suspected of murder and convicted for armed robbery in her mid-20s. She was later released and given the opportunity to teach basketball at a club for troubled youth. She made a success of this, attracting widespread acclaim and eventually going on to a successful career coaching college basketball and as a sports commentator.

Let’s assume that both lives contain the same aggregate amount of pleasure/joy and suffering. The only difference between them is the trajectory. Who’s life would you rather live? Dorsey, and others, think it is obvious enough that you would prefer to live JO Nospmis’s life.

The intuitive appeal of her trajectory over OJ’s could itself be taken as evidence for the importance of the shape of a life. But something more can be said too. According to Dorsey, and other narrativists, the shape matters because the value of the events within your life can be altered by their relationship with past and future events. OJ Simpson’s great achievements early in his life are undermined by his later downfall. We see the early achievements in a different light given what we now know. The reverse is true for JO Nospmis. Her early crimes and misdemeanours are redeemed by her later successes. We see her story as one of triumph over adversity, not downfall from glory.

The important point is that the value of any particular event within your life is not completely determined by that event in and of itself. It takes on additional meaning and value, depending on what happened before and after (i.e. on its relationship to other events). Being successful at a job interview might seem wonderful at the time, but what if taking up that job becomes the major causal contributor to your relationship breaking down? What if you are miserable and unhappy in the job itself? When you look back, you might rue your success, no matter how joyous it was at the time. It is not quite as sweet in light of the subsequent failure.

The fact that the value of an event seems to depends on its relations to past and future events provides a powerful compelling reason for thinking that shape matters to the value of a life. Most theorists cash this out in terms of the “narrative” relations between past and future events (i.e. they think that what matters is that your life tells a good story). Dale Dorsey suggests that other kinds of inter-event relationality might make a difference too. He just doesn’t specify what these might be, leaving narrativity as the only obvious candidate.

2. The Case Against the Narrativist View

I must say I find myself intuitively drawn to the narrativist view: it makes sense to think that the order and sequence of events has some effect on the overall value of a life. But Vitrano is not a fan of this. Having read her criticisms, and reflected a bit more on the problems with narrativist views, I tend to agree.

The basic problem is this. Life is complex and messy. It consists of many events and experiences — some good and some bad. Constructing a narrative out of this complex mess of details requires both simplification and interpretation. Some events have to be treated as important and significant, and others have to be ignored or overlooked. Some events have to be knitted together into a narrative arc (or other set of relations) and some events have to be discarded or made to fit that arc. None of this is straightforward. Different people might highlight different events and construct different narrative arcs out of the same mess of details. This could have a dramatic impact on how we value the life as a whole (if we assume that shape matters).

You can see this very clearly in debates about historical figures. Take, for example, the life of Winston Churchill. To many people, he is a hero and saviour. Biographers have written hagiographic accounts of his life. They emphasise his dynamism, his energy, his impressive roster of publications and public contributions, and, above all, his standing up to Hitler and leading Britain through the darkest days of WWII. Others take a different view. While not completely discounting his achievements during WWII, they highlight his apparent racism, imperialism, jingoism and war-mongering, and his history of bad strategic judgments. To them, he is closer to a villain. Both groups are looking at the same life — the same complex mess of events, dispositions and experiences — and constructing different stories. The truth about Churchill — if there is any such thing — is probably too complex too fit into a simple ‘villain’ or ‘hero’ arc. Yet simple moral fables are what we tend to look for when making stories of our lives.

In this example, we are judging the life of another person. But the same problem arises when we are evaluating our own lives. Many things happen to us as individuals. What we choose to emphasise and what we tell ourselves about events can make a big difference to how we value our own lives. Indeed, this is a key insight underlying a lot of contemporary psychotherapy. Depression and anxiety can often be attributed to the stories we tell ourselves about our selves. Therapists can help patients by offering alternative interpretations and getting them to tell more positive stories.

Looking at my own life, I find that I can interpret what has happened to me in a positive light — I have been reasonably successful in my educational and academic endeavours, I have a family and friends who seem to like me, I think I also continue to improve in many of my skills and abilities — but I can also see it in a negative light — I have squandered lots of opportunities, I often find that I am stagnating or coasting, and I frequently fail to live up to my own ideals in my relationships with others. Is my story one of continued success or one of repeated personal failure? I can go both ways on this, depending on my mood. The actual shape of my life (if there is such a thing) is epistemically opaque.

I have illustrated this problem, stylistically, in the diagram below. Each dot represents a life event. The two different pathways through life’s events represent two competing interpretations of the shape of life.

There is another problem lurking in the narrative view too. It faces particular problems when it comes to the natural shape of a human life. Although all human lives are different, most follow a typical arc: childhood is a time of growth and experimentation; adulthood is a time of focus and achievement; and old age is time of deceleration and gradual decay. In other words, to go back to the opening quote, most human lives peak and then fade away; they do not go out in blaze of glory. If we take the narrativist view seriously, this natural tendency to fade away could have serious implications for how we approach our lives. Should we all desire death as soon as we reach our peaks? As Vitrano points out, if taken to an extreme, the narrative view “could lead to the absurd conclusion that if one achieves a ‘once in a lifetime’ accomplishment…one is better-off committing suicide right afterwards so as to avoid the eventual decline that will follow” (Vitrano 2017, 574).

All of this convinces me that it is a mistake to place too much emphasis on the shape of one’s life to one’s overall assessment of its value. Vitrano goes further and argues that it means we should favour the hedonic view (that what really matters is happiness not shape), but I don’t follow her all the way to that conclusion. I still find myself clinging to some semblance of the narrative view. I just think that outside of extreme and obvious cases (e.g. the OJ Simpson case), the narrative shape of a life won’t make that big a difference to its overall value. Life is just too complex for that.

I think it is a mistake to reduce narrativity to plot diagrams. Narratives, modified by analytics, make up the overwhelming bulk of our conscious experience. They illustrate various strategies for living which we can experimentally "try on," some of which we will commit our identities to enacting. The arc of the narrative, in this context, is a feature, but not one that can be controlled. Being true to character, on the other hand, is a feature that can be controlled, and that provides stability and integrity to identities under stress.

ReplyDelete