Over the past year, I have read several books about Oxford philosophy in the mid-20th Century. This was the golden era of linguistic philosophy -- the time when Gilbert Ryle, John Austin and the ghost of Ludwig Wittgenstein stalked the seminar room.

It's odd that I have dedicated so much time to reading about this era. If asked for my opinion, I would say that I don't think much of it, or the philosophy it produced, although I appreciate its impact. But these books caught my attention and I thought it might be interesting to offer some very quick reviews of them.

The books are, for the most part, exercises in biographical or narrative history. They are about personalities as much, if not more, than philosophical doctrines. Consequently, my reviews won't focus on the substance of the philosophical positions defended by the different members of the Oxford School. I'll just focus on whether the books were insightful and enjoyable to read.

First, a little bit of background. The central tenets of linguistic philosophy are, perhaps, best summed up by one of its intellectual forefathers, the now-obscure Cook Wilson (1849-1915), who taught and inspired a number of its protagonists:

The authority of language is too often forgotten in philosophy with serious results. Distinctions made or applied in ordinary language are more likely to be right than wrong. Developed, as they have been, in what may be called the natural course of thinking, under the influence of experience, and in the apprehension of particular truths, whether of everyday life or science, they are not due to any preconceived theory...On the other hand, the actual fact is that a philosophical distinction is prima facie more likely to be wrong than what is called a popular distinction, because it is based on a philosophical theory which may be wrong in its ultimate principles.

(Wilson 1926, taken from Rowe 2023, p 80)

There is wisdom in what Wilson said. The error rate of grand metaphysical theories is likely to be high, and the zeal to create a coherent and compelling philosophical theory can lead us astray. Whether ordinary language is a repository of wisdom is, I think, more debatable, and whether ordinary language philosophy, as practiced by the likes of Austin and Ryle, ever got close to studying ordinary language (as opposed to the 'ordinary' language of a narrowly-circumscribed elite) is questionable. Although it is now widely condemned, I think Ernest Gellner's critiques of ordinary language philosophy -- in his controversial book Words and Things -- is more right than wrong.

Still, it would be churlish to deny that ordinary language philosophy exerts considerable influence over modern analytic philosophy. Close attention to words and concepts, precise analysis, technical detail, and argumentation, are all features of the modern philosophical literature, particularly in the Anglo-American world. Even in the areas of philosophy with which I am most familiar -- moral, political, legal and religious -- one feels the dead hand of Oxford gently nudging one in the back. Furthermore, Oxford philosophy in the middle 20th-century was not a monolith. As practiced by John Austin, ordinary language analysis was a pedantic and priggish exercise. But in the hands of others, there was something fun and exploratory about it. And there always internal resistance to it. Bernard Williams, Stuart Hampshire and Peter Strawson, for instance, both criticised and moved beyond the constraints imposed by the likes of Austin. And a group of female philosophers (more on them below) were also persistent gadflies.

Anyway, here are my reviews of the five books.

1. A Terribly Serious Adventure by Nikhil Krishnan

If you want a basic, very readable, introduction to ordinary language philosophy, this is the place to start. It's a comprehensive, yet breezy, overview of the movement from 1900-1960 (going by the cover), though primarily focused on the 1930s-1960s. It covers all the key movers and shakers, from Ayer to Wittgenstein, and many more in between.

What I most appreciated about this book was its attempt to put linguistic philosophy in its context, as partly a reaction to British Idealism, which dominated in the late 1800s, and partly an effort to modernise and professionalise the discipline. I also enjoyed the writing, peppered with mordant and colourful observations, such as this:

Under whatever name, linguistic philosophy -- or something descended from it -- still dominates the academic philosophy of the English speaking world. Rumour has it that brave evangelists have even managed to find converts in deepest France. (p7)

The occasional observations about the impact that the two world wars had on Oxford philosophy, both in terms of its personnel (who survived or was lucky enough to avoid the draft) and how they acted, were sobering. To be fair, this is a theme that crops up in all the other books I read, but consider this passage about Gilbert Ryle, who went on to have an outsized role in the movement:

He was born in the late summer of 1900, a lucky year to be born an English boy. Just a year older and there was every chance that he would have been one of the 149 boys from Brighton College who died at Ypres, the Somme or in Palestine...As it was, Ryle survived, eighteen years old at the Armistice, and ready to head for - or 'to go up' to - Oxford. (p 15)

In one of the other books -- I think it was the one by MW Rowe -- it is noted that there were no Oxford philosophers born between 1890-1897 that left any record of publications or influence. The reason 'why?' does not need to be stated.

2. The Fly and the Fly Bottle by Vid Mehta

This is the oldest book I read. Published in the early 1960s, it is a collection of articles by the New Yorker writer Vid Mehta. I read it largely because it kept cropping up as a reference in the other books. The articles bear the hallmarks of the New Yorker style (if you read the New Yorker, you will know). The articles are exercises in reportage: colour pieces about academics and their opinions and very well written for that. The opening chapter, in particular, is a masterpiece of metaphorical construction. Mehta, a former Oxford student himself, visited academics, interviewed them, and reported back about what they said, with some observations and asides of his own.

The book is divided into two parts. Only the first part is about philosophy and it centres on the controversy arising from Ernest Gellner's book-length critique of ordinary language philosophy. This is the book Words and Things that I mentioned in the introduction. As such, it ends up being something of an extended obituary for ordinary language philosophy, summarising the movement as it was dying out. Mehta is like a contemporary Gibbon, reporting on the decline and fall of a once proud empire. Parts of it are quite sad (relatively speaking). I was particularly struck by this reflection on John Austin (dead by the time Mehta wrote his book) by one of his close friends, Geoffrey Warnock:

"He was really a very unhappy man," Warnock said quietly. "It worried him that he hadn't written much. One lecture, "Ifs and Cans"...became famous, but it is mainly a negative work, and he published very few articles and, significantly, not a single book...To add to his writing block, he had a fear of microphones, and this prevented him from broadcasting...this was another source of unhappiness. He took enormous pride in teaching, but this began to peter out in his last years, when he felt that he had reached the summit of his influence at Oxford. Toward the end of his life, therefore, he decided to pack up and go permanently to the University of California in Berkeley...But before he could get away from Oxford, he died. (p 62)

Why did this strike me? There are a few reasons. Austin had a major influence on the development of ordinary language philosophy, post-WWII. He crops up everywhere. Any book you read about the period singles him out as its most influential figure. Not all the portraits are kind. Some suggest he was a tyrant and bully. But he was undeniably a piquant and influential figure who, as we will see below, played a crucial role in military intelligence during WWII, possibly critical to ensuring the defeat of Hitler. And yet here we have one of his closest allies and friends remarking on how unhappy he was.

Was this just the mistaken impression of a friend? Was it really true? I suspect it is more true than false. It resonates with my own experience of academia. With relatively few exceptions, many of my academic colleagues strike me as being unhappy people, at least when it comes to their professional lives. They seem overwhelmed with disappointment, frustrated by lack of motivation or foiled ambition, always creating the impression that they should have done (or should be doing) more. I don't exclude myself from this diagnosis either. I wouldn't say that I am unhappy, per se, but I certainly feel frustrated and unfulfilled more often than I would like. In my darker moments, I'm haunted by the image of Einstein furiously scribbling equations on his deathbed for his (never-to-be-completed) grand unifying theory. It makes me wonder whether academia is a bit like politics: do all academic careers end in failure (or at least the sense of failure)?

Anyway, back to Mehta's book. The second half of the book is not about philosophy. It is about history and historical method. Should historians try to discover the mechanics of civilisation (as Arnold Toynbee hoped to do) or should their aims be more modest? I found this half of the book more interesting than the first half, largely because the material was less familiar, but to explain why would take me away from the themes of this review.

Overall, enjoyable as it was at times, Mehta's book didn't quite work for me. There is not enough 'colour' to make his portraits interesting. While it is nice to know that Richard Hare used to write his philosophy in a caravan outside the front of his house, you would expect more details like this from a New Yorker-style piece. There were a few too many, unexplained, extended quotes from the figures themselves. It's like a book that doesn't know where it belongs: philosophical exposition, collection of interviews, investigative journalism or colour reporting?

3. The Women are Up to Something (by Benjamin Lipscomb) and 4. Metaphysical Animals (by Clare Mac Cumhaill and Rachael Wiseman)

Sometimes the publishing world gets wind of something and decides to capitalise on it. This often results in a flood of books hitting the market at the same time about the same topic. While this is, perhaps, understandable when it comes to contemporary and popular affairs, it is more surprising when the topic in question is four dead female philosophers and their experiences at Oxford in the mid-20th century. Nevertheless, that's exactly what happened with these two books, published in quick succession, by two different sets of authors. Both books are about the lives and philosophies of Elizabeth Anscombe Philippa Foot, Mary Midgely and Iris Murdoch. The Somerville Quartet, as one reviewer described them.

Each of these women is well known in their own right. Anscombe was Wittgenstein's literary executor and translated his final work (Philosophical Investigations) to English. She also published ground-breaking and highly influential work of her own, particularly in the philosophy of action. Philippa Foot was one of the leading figures in moral philosophy in the latter part of the 20th century. We have her to thank (or blame?) for the modern obsession with the trolley problem. Iris Murdoch was an influential writer and, to a lesser extent, moral philosopher. She is probably best known for her complex, psychological novels. Mary Midgley is a slightly more eclectic figure. She lived to be nearly a hundred and became influential later in life as a critic of modern evolutionary perspectives on human behaviour and morality, particularly as practiced and preached by the likes of Richard Dawkins.

Before reading these two books, I was most familiar with the work of Philippa Foot, and, to a lesser extent, Iris Murdoch (I've struggled through several of her novels). I had read some of Mary Midgley's papers critiquing Dawkins, but never thought much of them (they seemed, to me, to rest on a misreading and misunderstanding of his position). I knew Anscombe's work only by reputation and found some of its terminology intimidatingly obscurantist.

Both of these books take as their foundational conceit an observation once made by Mary Midgley to the effect that the advent of World War II, and the fact that the young men who would otherwise have dominated the philosophy seminars of Oxford were called up to serve, had a liberating effect on the women who were left behind:

The effect was to make it a great deal easier for a woman to be heard in discussion than it is in normal times. Sheer loudness of voice has a lot to do with the difficulty, but there is also a temperamental difference about confidence--about the amount of work that one thinks is needed to make one's opinion worth hearing.

(Mary Midgley, quoted in Lipscomb, p 39)

Both books are well written and very readable. I can recommend either (or both) to anyone interested in the four women. They share a similar thesis: that the four women developed their philosophical positions largely in opposition to the dominant trend in ordinary language philosophy. In particular, the books claim that all four thought that philosophy should be less about solving technical problems in linguistic expression and more about addressing real human problems, particularly in the land of morals and values. Lipscomb runs with this thesis the most, arguing that the women were all opposed to something he calls the 'Dawkins Sublime' (essentially, a reductionistic and scientific view of mankind). MacCumhaill and Wiseman are bit more circumspect, suggesting that the women were more interested in the idea of mystery and returning philosophy to metaphysics.

Jennifer Frey has written what, to my mind, seems like a plausible critique of both books, arguing that the picture of opposition that they paint is misleading. For instance, Anscombe, given her obvious links to Wittgenstein, was clearly less outside the Oxford norm than one might be inclined to think from reading these books. And Philippa Foot's work was largely a defence of a scientific and naturalistic view of morality, not an alternative to it. Overall, according to Frey, there is more disunity to what the four women had to offer than the books suggest. Based on what I have read of them, this sounds right to me, though I am not an expert on any of them. Even if Frey is right, there would still be a reason to write a book about all four of them. They did go to Oxford at the same time, they were friends and they did develop interesting philosophical positions of their own. Indeed, Frey suggests that what binds the women together, and what should be celebrated, is their intellectual friendship, not their common ideology. That's something to celebrate in its own right

Is one of the two books better than the other? I wanted to like MacCumhaill and Wiseman's more: it seemed appropriate to me that a book aimed at reinvigorating the inquiry into four female philosophers should be written by two women. But, on balance, I marginally preferred Lipscomb's. This was because it covered more of their lives and philosophical views (MacCumhaill and Wiseman rush through the final years). Also, MacCumhaill and Wiseman's book had some slightly (to me) grating historical speculation in it. They would frequently imagine occasions when the women may have met up or spoken to one another about a particular topic. For example, there are several scenes that start with phrases like "we might imagine" or "perhaps" X or Y happened. Obviously this helps with storytelling, and perhaps (look! I'm doing it too) all historians invent narrative details, but by the end of the book I found it jarring.

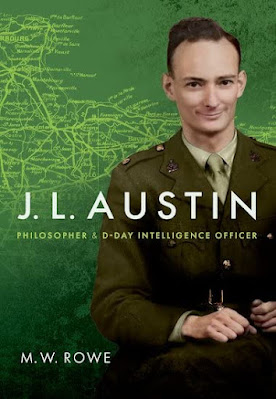

5. JL Austin: Philosopher and D-Day Intelligence Officer, by Mark W Rowe

The last book in the sequence is the most recently published (May 2023) and, as a consequence, the one that is freshest in my memory. It is an extended biography of the aforementioned, and deeply unhappy, JL Austin. As already noted, Austin was, along with Gilbert Ryle, the centre of the ordinary language movement in Oxford philosophy. Although he published little in his lifetime, through his Saturday morning seminars and extensive teaching, he exerted a significant influence over the method and style of mid-20th century Oxford philosophy. Every book about the era makes reference to this fact. And yet, until Rowe, there has been no book-length biography of him.

I went into this book with low expectations. Austin is not a philosopher that speaks to me. I think aspects of speech act theory are interesting, and I have made use of them in some of my own work on legal interpretation, but I never really took that directly from Austin, whose preferred vocabulary ('illocutionary acts', 'perlocutionary effects' and the like) always put me off. Also, none of the portraits of him in other works make him sound like an appealing figure. Consequently, this book was something of a revelation, not because it made me warm to Austin (it didn't and Rowe doesn't shy away from his flaws), but because I just really enjoyed reading it.

It is a classic 'fat' biography, full of historical detail and clearly the work of tremendous, painstaking research. If you want to know about every philosophical paper, debate, class, or seminar series Austin participated in, then this is the book for you. That might make it sound boring, but it is really not. I could have, perhaps, done without the extensive family tree and prehistory in the opening chapter, but beyond that I learned more from this book about the style, personalities and views of Oxford philosophy in the early to mid 20th century than from all the other books reviewed above.

Also, at the heart of the book, is a fascinating inquiry into what Austin did during WWII. It has long been known that Austin played a key role in British intelligence during WWII. Again, if you read histories of ordinary language philosophy, you will constantly come across allusions to Austin's 'glittering' war career and how he returned to Oxford after ascending the heights of the British military. But what exactly did he do? Austin never shared the details during his life. To work it out, you have to piece together fragmentary accounts and indirect evidence from numerous sources. That would take a long time. Fortunately, Rowe has done all this work for us and he shares his results in the middle portion of the book.

This was grist to my mill. I am not a WWII buff, by any stretch of the imagination, but I loved all the detail about the progression of the war, the intelligence operations, the brave work of the French resistance, the military strategy and planning, and the internal politics of the military bureaucracy. In very short outline, Austin rose to fame within the intelligence services for some early work on the North African Campaign (mainly in 1941). He was one of relatively few people to guess, based on the evidence, that German forces in North Africa were stronger than others were claiming. Then, from 1942 onwards, Austin led a unit within the intelligence service (nicknamed the Martians) that was instrumental in planning the D-Day landings. This required a lot of patient and piecemeal work, figuring out appropriate landing sites and the distribution of German defensive fortifications. It might sound dull, but it was detailed, high pressure work, and it was important to the success of the Normandy invasion.

One thing that emerges from this section of the book, of course, is that Austin was not some lone genius in the military complex, single-handedly responsible for the success of the D-Day landings. It was the coordinated work of many individuals that made the crucial difference. This is something you get from all good histories of WWII and is, I think, one of the positives to take from the war: when our backs are to the wall, we humans can cooperate on a large scale to achieve a desired end.

There is also plenty of philosophy in the book. Rowe takes the time to explain and critique a lot of Austin's post-war philosophical work. The end result is not a light and breezy read, but it is a rewarding one.

And that's it. Five books. Reviewed.

,_by_Turner_(1810)_crop.jpeg)

I have read about Ryle. Mostly in references or footnotes. Thanks for this post.

ReplyDelete